Confessions of a Sandernista

Sam Copeland

Platypus Review 126 | May 2020

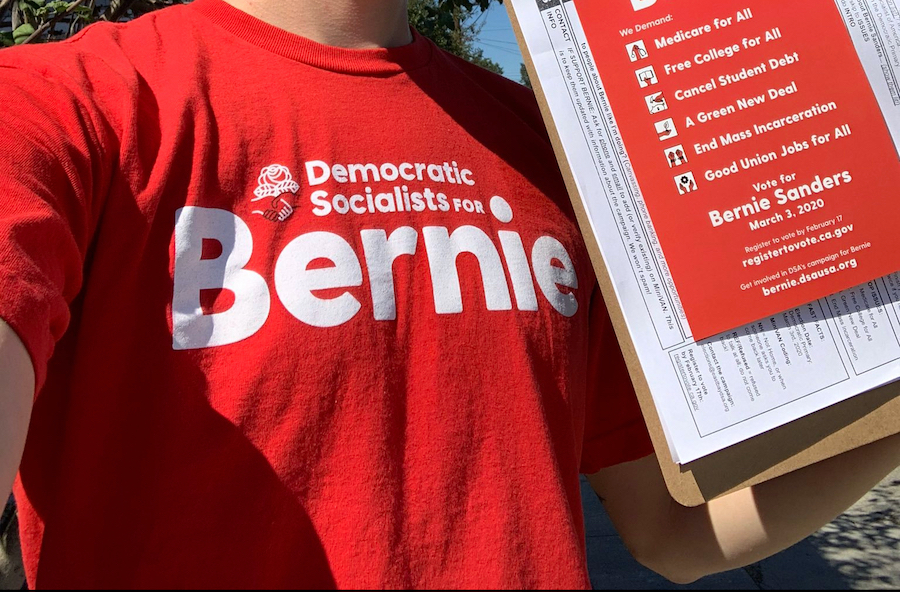

ON FEBRUARY 14TH I CAUGHT A BOLT BUS from the NYC Port Authority to the 30th St Station in Philadelphia. Once in Philly I headed for the house of a DSAer [member of the Democratic Socialists of America] whom I had never met before. Then he and I climbed into his little Toyota sedan and embarked on our 11½ hour drive down to South Carolina. We were headed for Charleston to canvass for Bernie Sanders.

In Charleston I encountered the exoticisms of the South for the first time: the barbecue, the palm trees, the old southern woman who told me, “We have northern friends who come down in the winter — we call that the Second Invasion!” Hope abounded on the canvassing trail. I spoke to only one Biden supporter. Everyone else was either an outright Bernie supporter or thought he was “an honest guy.” After canvassing we would convene with fellow canvassers at bars downtown. I met a lovely girl: she was beautiful, a musician, a socialist. I rode back to New York in her car. We read each other poetry going up I-95.

On February 29th Joe Biden won 48.7% of the votes in South Carolina, walking away with twice as many delegates as Sanders. Shortly thereafter Buttigieg, Klobuchar and Steyer dropped out and endorsed Biden, while Warren stayed in and undercut Sanders through the next brutalizing round of primaries. The hope and momentum surrounding Sanders evacuated the scene. By April 8th he officially ended his campaign. The girl and I have not kept in touch.

It is too early for the Owl of Minerva to take wing from the headstone of Bernie Sanders’ 2020 presidential campaign. For that very reason I want to capture this moment of openness, before future events give our actions a determinate significance. There is one purely formal fact of which we may be sure: Bernie Sanders, the social phenomenon and its legacy, cannot be dismissed as a blip or detour in the history of the Left. Sanders’ essential, even dialectical, relation to the Left is shown in the fact that whatever one’s belief about what the prevailing tendency of today’s Left is, Sanders appears as the highest fulfillment of this tendency. If one believes that the Left has reduced itself to the trailing fringe of the Democratic Party then Sanders is, if nothing else, the leader of this trailing fringe; if one believes that the Left is in the process of raising itself out of the ashes, starting with a modest electoral program, then Sanders spearheads the long dialectic towards reconstitution; if one sees the Left as a reformist movement for the spread of Nordic social democracy, then Sanders is the most successful representative of this movement in the United States. Even conservatives who see the Left as a gang of anti-American communists must feel vindicated by Sanders. Thus, like the corpse of Polynices, Sanders directly embodies the antinomies of proletarian thought.

For those of us without a clear belief about the nature, status, or prevailing tendency of the current Left, Bernie Sanders appears not as a complete object but as a kind of portal into an unknown future. In our present condition, wherein futurity has been foreclosed under neoliberalism, Sanders seemed to present an opportunity to jumpstart history. On a sinking ship, an escape hatch may have a wall of water behind it rather than a dry upper deck, but what does that matter if you’re already up to your neck? Thus the question of hope was external to the Sanders campaign: did we, after all, really believe that Sanders could win the nomination? let alone become president? let alone get even a disfigured compromise on his platform through Congress? Even granting all of that and more, did we really believe any of this would get us one step closer to socialism? The Sanders campaign was not an exercise in hope, however. It was rather an attempt to “not go gentle into that good night / rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

Nonetheless, Sanders is only one of many who are peddling their respective brands of post-neoliberalism. What sets Sanders apart is of course his stated commitment to leftist principles, compounded with his apparent personal integrity, which leads us to believe that his stated commitments are genuine. One might retort that, however deep Sander’s commitments, he is mistaken to think that his principles are truly leftist. Thus we get the common complaint that Sanders is not a “real socialist.” But to complain that Sanders is not a real socialist is an arrogant, ahistorical absurdity. This is not a revolutionary moment. The historical conditions are lacking for a Eugene Debs, much less a Karl Kautsky, much less a V.I. Lenin. If Luxemburg had written Reform or Revolution under conditions such as ours she would have been rightly laughed out of the room. Revolutionism breaks down under the present conditions and fails to recommend any action, even resignation, from its principles — it becomes a religion for beautiful souls. Today the Left is in such a state of decrepitude that qualitative concerns about organization, theory and tactics have reverted to quantitative concerns about numbers and enthusiasm. For lack of the latter today’s Left cannot even begin to reconstitute itself: even the class consciousness of existing socialists is hindered by the absence of sufficiently vibrant and populated leftist institutions. If opportunism is ‘making an end in itself out of the growth of the party (or movement),’ then today there is no practical distinction between opportunism and orthodoxy.

The Keynesian, FDRist, Bonapartist, etc. appearance of Sanders’ program reflects the recognition of this fact. The value of reformism has been recognized by all of the great revolutionaries for its role in coalition-building: it provides a practical basis for organizing civil discontents around leftist ideals. Sanders has used his reformist program to create a national coalition virtually ex nihilo. In the process he has affected a partial rehabilitation of the word ‘socialism’ in mainstream American discourse, which is no triviality. To discount the effect which these developments have had on people’s openness to “real” socialist ideas is a bald error, and one which is contradicted by numerous facts, like that Platypus’s own ranks have swelled in concert with the Sanders phenomenon. Even if Sanders’ strategy for resurrecting the Left proves not to be the right one, he has carried it further than any other living leftist. To complain of his not being a “real socialist” is to disguise one’s impotence by casting it as a choice.

Sanders may be faulted for casting his allegiances with the Democratic Party, for endorsing Hillary Clinton and now Joe Biden, etc. One might make the charge that Sanders’ campaign has only accelerated the Left’s liquidation into the Democratic Party. One should ask, however, whether it is likely that the Democratic Party leadership is happy about the Sanders phenomenon. Millions of registered Democrats who once supported Obama with a song in their hearts now hold deep animus towards the DNC, the Clintons, Joe Biden and, yes, even Obama. When Biden inevitably loses to Trump, establishment Democrats will blame Sanders and his supporters for spoiling the election, driving the wedge deeper. The Democrats will have a defeated, splintered party. No Trotskyist insurgency could dream of doing them so much damage!

Furthermore, Sanders forced the institutions that surround the Democratic Party, such as The New York Times, MSNBC, The Daily Show, etc. to unmask themselves. The very modesty of Sanders’ program was the crucial factor: confronted with a slew of mildly Keynesian policy proposals these purportedly progressive institutions descended into a belligerent panic. It was easy for them to pay lip service to wealth equalization, antiracism and environmentalism until someone made the provocation of acting on these fine expressions. Their commitment to neoliberalism is now in the light of day for those who still have eyes to see, which creates new opportunities for left propaganda. Whether the Left will exploit the opportunity remains to be seen. If it cannot then the fault lies not with Sanders but with the Left’s radical intelligentsia.

Sanders presents us with a task. He has created a movement of millions of Americans with, if nothing else, a stated interest in socialism; he has divided the Democratic Party; and he has publicly exposed the fact that even modest progressivism lies outside the horizon of the neoliberal consensus. If we cannot make something of this opportunity then we give up all pretense of being political agents at all, and our “leftism” amounts to a mere consumer identity. Bernie Sanders is handing us a torch, and we will now see if we are not too cowardly to seize it.

When I was canvassing in Charleston I felt I was part of a leftist, or perhaps pre-leftist, movement at the level of passion, which, as Hegel said, is the first condition for anything great to happen in history. Bernie Sanders harnessed a hitherto sundry array of passions into his movement: frustrations with the system, thirsts for justice, appetites for destruction. These passions are for the most part inchoate and tending towards negotiations over the terms of the sale of labor-power — but therefore those of us who aspire to the tradition of Marxism must work to cultivate this raw material and to endow it with a socialist form. To that extent Sanders provides us, not with guarantees or hopes or even improvements, but with a task through which we may assume a minimal comportment towards the future. At the same time, however, the existence of the Sanders phenomenon signals that today the future itself has become antiquarian. There is a rational kernel to the concerns about his age: Bernie Sanders is a ghost (or, if you prefer, a spectre) of the 60s Left. His candidacy is as nostalgic as a Beatles song returning to the Billboard Hot 100, and now that his candidacy has ended he is a ghost in a double sense. For he has become one of Benjamin's ghost: haunting the Earth, awaiting release through a redeeming historical act. History has already condemned Bernie Sanders to his place in the pantheon of the Left, as it has condemned us to bear his legacy on our shoulders, against our will. Therefore, in a time such as ours, where one can be neither a Jacobin nor a Bolshevik, one at least can be a Sandernista.| P