On the use and abuse of Nietzsche for the Left

Ethan Linehan

Platypus Review 122 | December 2019 - January 2020

Poor wretches have no idea how corpselike and ghostly their so-called “healthy-mindedness” looks.

— Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy (1872)

Man is something that shall be overcome. What have you done to overcome him?… Man is a rope, tied between beast and overman, a rope over an abyss… What is great in man is that he is a bridge and not an end: what can be loved in man is that he is an overture and a going under.

— Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883)

LATELY QUITE INDISCRIMINATE WHEN APPLYING THE CENSOR’S PEN, the Left at present showcases no great respect for Friedrich Nietzsche. Few figures, excepting perhaps Adam Smith,[1] have received such scorn from the Left as has Nietzsche. The philosopher of ice and high mountains has all too assiduously been banished to the depths of rightwing reaction or derided as a brief flirtation only fit for male teenage angst. This ubiquitous rejection says very little about Nietzsche and very much about the historical impoverishment that has bedeviled the Left for generations. If the Left has no time for Nietzsche, it is to its own detriment. For in their haste to cast aside Nietzsche, the Left has shown their cards. Their incensed dismissal of him betrays the truth: Nietzsche’s project and the contemporary Left really have nothing in common. Nietzsche does us no favors in this regard because he never claims Left affiliation. The Left historically was defined by its utopia, by its vision for the future, by its progressivism, and by its striving for radical change. The Left is about freedom, an opening of possibilities, and an overcoming of the limitations of what currently exists. Nietzsche, though certainly he champions an opening of possibilities, trenchantly and consistently put pressure on the very concept of progress and showed it to be shot through with antinomies, but therein lies his importance for the Left as we must take the time to see. Much like Adam Smith and Rousseau, Nietzsche’s thought as a philosopher of freedom pervades a very rich and very much forgotten history on the Left that demands urgent recovery. The Left per se has long been attracted to Nietzsche owing to his devastating indictment of the status quo and his insistence that modernity itself is only a rung on the ladder to higher things. If my attempt to play archaeologist for three generations of serious, critical appraisal of Nietzsche does not prove illusory, then the Left today, by uncritically rejecting this history, evinces it is de facto not a Left worthy of the name.

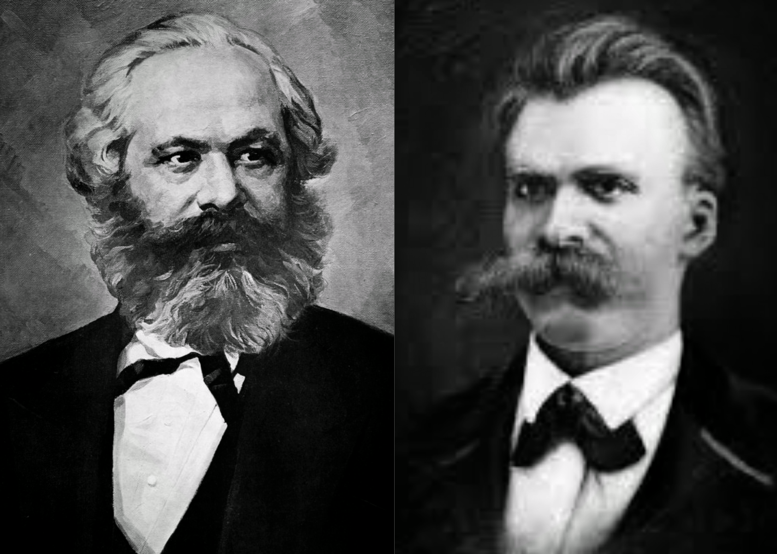

From Marx to Nietzsche

One could sufficiently abridge the intellectual orientation of the 19th century thus: attentive to history. As Nietzsche scholar Peter Preuss put it, “the 19th century had discovered history and all subsequent inquiry and education bore the stamp of this discovery. This was not simply the discovery of a set of facts about the past but the discovery of the historicity of man.”[2] The critical recognition of history as the site of an unfolding drama in which humankind must play an active role was the indelible mark of the Enlightenment; this tradition reached its philosophical zenith in Hegel. However, history took on a new specificity post-Industrial Revolution. Marx is the most significant name to have optimistically registered the new possibilities and problems of history, but Nietzsche quietly took the stage once the future of history became mired in melancholia. Nietzsche was born just four years before the whole Hegelian system was dashed on the rocks in the wake of European-wide revolutionary defeat. It is no coincidence that this is when Marx’s insights first coalesced. Nietzsche lacked a dialectical understanding of capitalism (the breakthrough we attribute to Marx), but Nietzsche’s thought always remained immanent to the contradictory nature of bourgeois society in crisis. One commonality that holds between Marx in dialogue with Nietzsche is their common commitment to dialectics; this is most evident in their shared usage of the German verb aufheben (“sublation” or “overcoming”). That is, Nietzsche’s project is amenable to a Hegelian/Marxian framework, despite the mental resistance within Nietzsche on that framework (late in life when reflecting on his earliest work The Birth of Tragedy, Nietzsche considered his insistence on dialectics a folly of youth).[3] Nietzsche is closer to the dialectical tradition than his 20th century Heideggerian reception would have you believe. Nietzsche indeed should be considered the last Hegelian. The unity of purpose between Marx and Nietzsche is that their common project is both a continuation of and a break from their Hegelian roots. Nietzsche is marked, as much as Marx, as symptom and spokesperson of a pathologically symptomatic and unhealthy age. As Chris Cutrone has written, Nietzsche describes the modern condition as “an illness, there is no doubt about that, but an illness like pregnancy is an illness.” After nine painful months, pregnancy results in new life. Pregnancy is a kind of illness for the mother, but it is the locus of life for the baby. It is only because of the mother’s sacrifice to endure the illness and not to seek to end the pregnancy that the baby can be born. Pregnancy is a problem of potential. Pregnancy is only an illness insofar as it has not run its course. Once the baby is born, the pregnancy is made worthwhile.[4]

In this same way, Cutrone continues, capitalism is a problem of potential. We suffer from the unrealized potential of capital. Capitalism is not an illness to be cured. It is not to be eliminated. Rather, like a pregnancy, capitalism is to be successfully gone through, to bring forth new life. Socialism haunts capitalism like a “specter,” like the baby kicking in the womb. But attempts at birthing socialism have miscarried or been aborted before. Karl Marx called revolution the “midwife of every old society pregnant with a new one.” Socialist revolution would make socialism possible, but it would not birth a ready-made socialism. An infant, especially one not yet born, is not mature enough to live. History is riddled with socialist revolutions that were delivered but were non-viable. Maybe socialism is merely a “fever dream” that chronically recurs but always passes with time. Socialists hitherto have been far too unhealthy to successfully give birth to a new society. They mistook capitalism as an illness to be cured, rather than what it actually was: a symptom of potential new life in the process of emerging. Nobody thus far has supported the pregnancy. This would mean seeing the symptoms through to their completion and not trying to stop or cut them short.[5]

Nietzsche dared to ask “Are there perhaps — a question for psychiatrists — neuroses of health?”[6]What symptoms in this society point beyond themselves? For both Marx and Nietzsche, following Hegel, modernity is not to be apotheosized as the “end of history”; rather, modernity demands to be made transitional. Nietzsche and Marx, unlike Hegel, stress future history rather than the past — for example, Nietzsche did not pine for a return to an idyllic Hellenic age. Nietzsche as acute psychologist has insights into the life of a subject living under conditions of bourgeois society in disintegration that remain relevant so long as we are tasked with overcoming our decadent condition.

Nietzsche after death

Following his descent into madness and untimely death, Nietzsche found fans and critics on the Left throughout the world. In an 1897 questionnaire for Leipzig workers’ libraries, it was reported that Nietzsche’s works had been borrowed far more often than those of Marx, Lassalle, and Bebel.[7] The highly volatile political consciousness of the late 19th and early 20th centuries put Nietzsche to ever more conflicting purposes. The multifarious uses to which Nietzsche was put now, in hindsight, represent the ongoing crisis within Marxism. Franz Mehring could unequivocally damn Nietzsche as the mouthpiece of capitalist reaction, charting an accommodationist and parliamentary course to pseudo-action rather than revolutionary action, while other members of the SPD could feel as though they and Nietzsche were kindred free spirits, “outsiders” full of dissent against the established order. It was during the Revisionist Dispute that efforts to synthesize Marx with Nietzsche intensified, especially when Left Nietzscheans strayed ever further rightward. One critic in the SPD argued that Nietzsche must be reckoned with; he must be internalized and at the same time overcome.[8] Naturally, this course charted many paths. Clara Zetkin, for instance, treated Nietzscheanism as merely an episodic fascination quite useful during a romantic stage in one’s politico-intellectual development. Others, like Victor Adler in Austria, infused into social democracy Dionysian impulses designed to rouse an awareness of power in the nascent proletariat. J. Karmeluk’s 1904 Proletarian Sermon from the Mount: An Intermezzo from the Transvaluation of Values made from Nietzschean themes a socialist gospel fit for bringing paradise on Earth. Pre-revolutionary Russian Marxism got the most mileage from Nietzsche in the early 20th century, too often by positive appropriations of Nietzschean statements as readymade values for a socialist utopia. Trotsky’s famous critical eulogy for Nietzsche stands out as a bright spot in a sea of reactionary darkness in Russian philosophy. Lunacharski, Volski, Bogdanov, and Bazarov found support for their own revisions of Marxism in the professed Anti-Christ, through conservative transmutations of him into an individualist proletarian hero reminiscent of his usage by Mussolini or into a coercive immoralist in charge of the future commune dedicated to stifling all individualism. This movement famously and deservedly earned Lenin’s scorn, thereby removing Nietzsche from Russian Marxism indefinitely following 1917.

Nietzsche’s reception languished in existentialist hell for the next two decades, suffering under the weight of Heideggerian disgust with modernity. Existentialism is clearly marked by its place in the wake of worldwide revolutionary failure. Freedom becomes a nausea-inducing, ontologically-given burden to be regretted rather than a daunting but urgent social task. Freedom is posed as an individual matter, both theoretically and practically. The existentialists participate in an antinomy of individual voluntarism and deterministic economism (which they ascribe to Marxism) — an antinomy that Marxism itself had already overcome. Even the Marxist-friendlies like Sartre acknowledged the resignation in their retreat from Marxism as a political project. They tried to find in the apolitical Nietzsche a safe haven for mere contemplative thought, but this Schopenhauerian nausea with life and paralysis of action were already rebuked by 1872.

Nietzsche and the Frankfurt School

Circumstantially removed from the homeland of Marx and Nietzsche by a fascist movement claiming to be creating a race of Supermen, the expatriate members of the Frankfurt School pondered, however counterintuitively, “What would the Nietzschean corrective to a post-1917 world be?” Nietzsche proved to be both a provocation and an indispensable asset to a reconsideration and revitalization of Marxism from within. For the Frankfurt School, Nietzsche’s work gained a renewed relevance as critical voice against the vulgarization of Marxism. Dating back to the split between Right and Left Hegelianism, there existed the tension that Marx identified between affirming history and struggling over history. Nietzsche indicated that the unbowed “cheerfulness” characteristic of the late 19th century actually displayed a self-dissolution and weakness:

Could it be possible that, in spite of all “modern ideas” and the prejudices of a democratic taste, the triumph of optimism, the gradual prevalence of rationality, practical and theoretical utilitarianism… might all have been symptoms of a decline in strength, of impending old age, and of physiological weariness? These, and not pessimism? Was Epicurus an optimist — precisely because he was afflicted?[9]

Nietzsche is denigrated as a philosopher that holds too tightly to contradiction, but this is a most helpful contrast with the vulgar Marxism that paves over contradiction and flattens out a dialectical reality. During the Revisionist Dispute, Marxism succumbed to the Hegelian split through its belief and faith in steady progress, in its affirmation of history and its institutions being on its side always. Marxism, thoroughly revised in the old liberal progressive fashion that Nietzsche detested, required a Nietzschean corrective:

Nietzsche, as early as 1873, heaped scorn upon the “Hegelian worship of the real as the rational,” which he further castigated as a “deification of success.” He accused Hegel of offering an “apotheosis of the commonplace [or ‘everyday’]” in order to ingratiate himself with the “cultural philistine, who… conceives himself alone to be real and treats his reality as the standard of reason in the world.” According to Nietzsche, David Strauss is being a faithful Hegelian when he “grovels before the realities [or ‘conditions’] of present-day Germany.” In the following year Nietzsche went on to accuse Hegel of “a naked admiration for success” and an “idolatry of the factual.”[10]

The culmination of Hegelian philosophy took place for Nietzsche when he recognized that his fellow Hegelians were decadent defenders of the status quo, that their philosophizing hardly comprehended their own time in thought, and that Nietzsche had to posit what was integral to his own unhealthy age in order to advance beyond it. Nietzsche is the antidote to the diseased bourgeois “Last Man” satisfied with himself — a critical perspective that Walter Benjamin and Theodor Adorno felt was most congenial to Marxism.

Marx consistently expounded the bourgeois realization that “all history is nothing but a continuous transformation of human nature.”[11] Nietzsche did not disagree: “All philosophers have the common failing of starting out from man as he is now and thinking they can reach their goal through an analysis of him. They involuntarily think of ‘man’ as an aeterna veritas, as something that remains constant in the midst of all flux, as a sure measure of things. Everything the philosopher has declared about man is, however, at bottom no more than a testimony as to the man of a very limited period of time. Lack of historical sense is the family failing of all philosophers.”[12] As Preuss said, “History is the record of [our] self-production: it is the activity of a historical being recovering the past into the present which anticipates the future. With a total absence of this activity, man would fall short of humanity: history is necessary.” But what if historicism takes over? What if history becomes about collecting facts that are “to be left as they were found” instead of being life-affirming and life-creating? Nietzsche argued this dangerous and deadly misstep had occurred and must be overcome. One must break with one’s given past in order to live, in order to have a future. History is no passive, disinterested thing at all, but a task for life.

By contrast, taken in by an affirmative reading of amor fati, Gunther Anders felt comfortable saying in 1942 that “Nietzsche did not offer a positive transformation of the world, but instead an acceptance of the world as it is… Perhaps one can use Marx to interpret Nietzsche, but not vice versa. Nietzsche is not a revolutionary who wanted to transform the world; he has merely erected an image, he does nothing for his goal.” Against this premature dismissal Adorno, following Benjamin, utilized Nietzsche’s critical understanding of history for a Marxist critical theory of the “philosophy of history” in order to re-introduce the Marxist concept of regression. For Nietzsche the present is the starting point for a critique of and reappropriation of the past. Benjamin adds the twist that the past indeed judges the present, and that we have fallen below a higher threshold reached long ago. If history is meant to serve life, then what needs might our history be failing to meet? Is our history in constellation with an anterior epoch? Adorno said:

As a precondition of the discussion we must acknowledge that Nietzsche’s entire discussion occurs in the realm of ideology. We must thereby ascertain the real motives that lie hidden beneath the ideological motives. Nietzsche’s critique of culture has, despite his categories, identified certain aspects of the social problematic that are not given per se in the critique of political economy. He has developed certain critical intentions farther than they have been elaborated in the post-Marxist tradition. We need to decipher Nietzsche in order to see what kind of fundamental experiences lie behind his approach. I believe that one will then arrive at things which are not so separate from the interest of most people… Here precisely lies the motive that binds us to Nietzsche. Nietzsche […specifies…] those things that in reality are ideology. One can pinpoint in Nietzsche those elements where his theory is true. He perceives that not only democracy, but also socialism has become an ideology. One must formulate socialism in such a way that it loses its ideological character. In certain critical respects, Nietzsche progressed further than Marx…[13]

Horkheimer, reinforcing Adorno, said “the expression that certain structures assume in Nietzsche is not merely a reflex but represents something essential.” Nietzsche is often reduced to one particular structure, his attack on the Christian religion, but even this reduction shows his relevance and his situatedness as a symptom of capital. With Engels’ specification, Nietzsche’s immanent critique of Christianity should recall his timeliness in a society where the rule of capital is breaking up: “For a society in which commodity production prevails, Christianity, particularly Protestantism, is the fitting religion.”[14] After proclaiming the death of God, Nietzsche asks, “Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?” This recalls Marx’s attempt to eliminate alienation to make us all into self-legislating agents capable of our own value creations. To transform the world through Hegelian philosophy would be to make humans in reality the gods that Hegel made them in thought.

Nietzsche at the crossroads

The question is, do we still need Nietzsche to throw cold water on a naive faith in steady and non-contradictory progress? The history of the 20th century gives no indication otherwise. We are consistently told “the struggle goes on.” Any thinker of use has been pushed out of reach. The New Left’s long march through the institutions left a tornado’s trail of scholastic destruction in every department in the Western world; no one teaches from the perspective that the best of the Left once critically held dear. The Left (Marxist and other currents in tandem) has invidiously prostituted Nietzsche to anyone reaching for him, voluntarily ceding ground to any trend from postmodernism to proto-fascism: The Left in their smugness is content to allow the claim recently made by Jacobin Magazine to stand: “[Nietzsche’s work] in its essence… belongs to the right.”[15] Every month it seems a new reader discovers in Nietzsche something “problematic” for what they assume must be the first time. Expect newfangled (the same old) defamation campaigns to be trotted out by the Left here in the year of Nietzsche’s 175th birthday. Leftists will again try to locate “the thinker’s own extreme-right views” in a “German nationalist anti-semitism” so patently ridiculous and long ago disproven, or perhaps they will go in for the “aristocratic elitist megalomaniac.” The real Nietzsche died and remains dead, and the Left killed him. Any critical purchase he could have on our moment continues to bleed to death under our knives.

Most relevant is how the Left today consistently stumbles over Nietzsche’s scathing remarks about socialism.[16] Nietzsche’s critique of socialism requires the proper resonance with Marx’s. They both spring from the same discontent with the bourgeois project of freedom. How does one paradoxically reconcile Nietzsche’s disparaging comments about socialism with the Marxist conclusion that socialism, with its emancipatory intent, clearly addresses one of Nietzsche’s main worries — a decadent society committed to unhealthy values? Nietzsche famously attributes a politics of ressentiment and a “pessimism of indignation” to the “socialist rabble” and the “apostles of revenge.”[17] Of course the socialism that Nietzsche had in his sights would not and did not escape Marx’s gaze either. Marx is mistakenly considered the founder of the socialist movement; rather, it was an ongoing movement stuck in the throes and birth pangs of self-discovery. Marx was in fact socialism’s harshest and most necessary critic. Nietzsche is known as a critic of socialism, and so should Marx be. The most prominent socialist criticized by Nietzsche was Eugen Dühring; Marx and Engels published two major works criticizing Dühring. Marx wrote in an 1843 letter that “communism… is a dogmatic abstraction; in which connection, however, I am not thinking of some imaginary and possible communism, but actually existing communism… This communism is… still infected by its antithesis: private property.”[18] It is not by accident nor from malice that Marx calls communism “brutish,” “completely crude,” “thoughtless,” consumed by “greed” and “envy,” and possessed by “the urge to reduce things to a common level” — a “leveling-down process.”[19] All very Nietzschean! In many ways the secular socialists were more retrogressive then the Christians insofar as they hoped to preserve and make eternal social relations that Christians had long been hoping to undermine and make transitional. Marx too scorned the much heralded equality of socialism only to be achieved when we are all equally low in the gutter. The discontents of capitalism cannot avoid reproducing the pathology of this society. Marx’s hope was that the movement for socialism could be honest about being a one-sided negation born from ressentiment, could be self-aware about its aims and methods in pursuit of aufheben; for that it was necessary Marx’s critical perspective become internalized: “If we have no business with the construction of the future or with organizing it for all time, there can still be no doubt about the task confronting us at present: the ruthless criticism of the existing order, ruthless in that it will shrink neither from its own discoveries, nor from conflict with the powers that be.”[20] Nietzsche likewise hoped that the “herd without a shepherd” would philosophize with a hammer, would not be pleased with itself, but would re-evaluate itself and strive always for self-overcoming, to be more than the beasts they were before and the mere men they were at present:

Mankind surely does not represent an evolution toward a better or stronger or higher level, as progress is now understood. This ‘progress’ is merely a modern idea, which is to say, a false idea. The European of today, in his essential worth, falls far below the European of the Renaissance; the process of evolution does not necessarily mean elevation, enhancement, strengthening.[21]

Herbert Marcuse once said, “If Marx is right, then Nietzsche is wrong.”[22] But what if the corollary is true? Perhaps, until Marx is right, then Nietzsche is. The difference is between what Nietzsche called “the optimist of 1830” versus “the pessimist of 1850.” While Marx remained insistent that the ongoing movement for freedom would advance to ever-greater heights, Nietzsche primed us for a lifetime of decadence culminating in the Last Man. That Nietzsche understood his dialectical style as a relic of his infantile intellectual innocence takes on more significance considering how dialectics characterized the thought of an entire society in its youthful spring (Rousseau, Kant, Hegel, et al), whereas the society characterized by the abandoned dialectic totters around in its senility and old age, demanding to be put down.

One could treat capitalism as just the final rotten stop on a long road of meaningless suffering and subsequently embrace the nihilism, but neither Marx nor Nietzsche would be satisfied. We are tasked by them with giving a meaning to our suffering — the same suffering we in fact created and recreate daily. The madman of Sils Maria surely suffers from a dearth of ready-to-hand categories of political economy and therefore leaves us irresolute vis-à-vis the finer points of the political struggle to overcome our out-of-control state of unfreedom. Nevertheless, Nietzsche remains relevant on this side of emancipation from capital because he brings to light important antinomies of bourgeois thought, certain necessary appearances of the crisis into which society has stumbled blindly. It is he who sits in Judgment’s chair awaiting us to overcome our debased condition in service of life. The price we pay for leaving Nietzsche buried under the calumny from the contemporary “Left” is the foreclosure of the possibility of creating a critical Left up to the task of changing the world.[23] | P

[1] Spencer Leonard, “Adam Smith, Revolutionary,” Platypus Review 61 (November 2013), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2013/11/01/adam-smith-revolutionary/>. [2] Peter Preuss, Introduction to Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Advantage and Disadvantage of History for Life (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1980), 1. [3] Friedrich Nietzsche. “Attempt at a Self-Criticism” (1886). [4] Chris Cutrone, “The future of socialism: What kind of illness is capitalism?” Platypus Review 105 (April 2018), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2018/04/01/the-future-of-socialism-what-kind-of-illness-is-capitalism/>. [5] Ibid. [6] Nietzsche, “Attempt at a Self-Criticism.” [7] August Pfannkuche, What Does the German Worker Read? Answered by Means of a Survey (Tübingen and Leipzig: Mohr, 1900). [8] A version of this argument can be found in Samuel Lublinski, “Nietzsche und der Sozialismus,” Europa: Wochenschrift für Kultur und Politik 1, no. 22 (June 1905). [9] Nietzsche, “Attempt at a Self-Criticism.” [10] George L. Kline, “Presidential Address: The Use and Abuse of Hegel by Nietzsche and Marx,” in Hegel and His Critics: Philosophy in the Aftermath of Hegel, ed. William Desmond (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 5. [11] Karl Marx, The Poverty of Philosophy (1847), available online at: <https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1847/poverty-philosophy/>. [12] Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human (1878). [13] Theodor W. Adorno, Günter Anders, Max Horkheimer, Herbert Marcuse, Ludwig Marcuse, and Friedrich Pollock, “Discussion of a Paper by Ludwig Marcuse on the Relationship of Need and Culture in Nietzsche (July 14, 1942),” Constellations 8, no. 22 (March 2001): 132-134, available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/wp-content/uploads/readings/nietzscheneed_frankfurtschool_constellations8_1.pdf>. [14] Friedrich Engels, “Synopsis of Capital” (1868), available online at: <https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/1868-syn/index.htm>. [15] See: <https://jacobinmag.com/2019/01/neitzsche-heidegger-ronald-beiner-far-right>. [16] See: <https://www.jacobinmag.com/search?query=Nietzsche>. [17] Nicholas Buccola, “‘The Tyranny of the Least and the Dumbest’: Nietzsche’s Critique of Socialism,” Quarterly Journal of Ideology 31, no. 3 (2009). [18] Marx, For the ruthless criticism of everything existing (letter to Arnold Ruge, September 1843), available online at: <https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1843/letters/43_09-alt.htm>. [19] Marx, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts (1844), available online at: <https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1844/manuscripts/preface.htm>. [20] Marx, Letter to Ruge. [21] Friedrich Nietzsche, The Anti-Christ (1895). [22] Adorno et al., “Discussion of a Paper,” 133. [23] For more on Nietzsche, see: Sunit Singh, “Nietzsche’s untimeliness,” Platypus Review 61 (November 2013), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2013/11/01/nietzsches-untimeliness/>.