The revolution marooned: Cuba and the Left

Ethan Linehan

Platypus Review 114 | March 2019

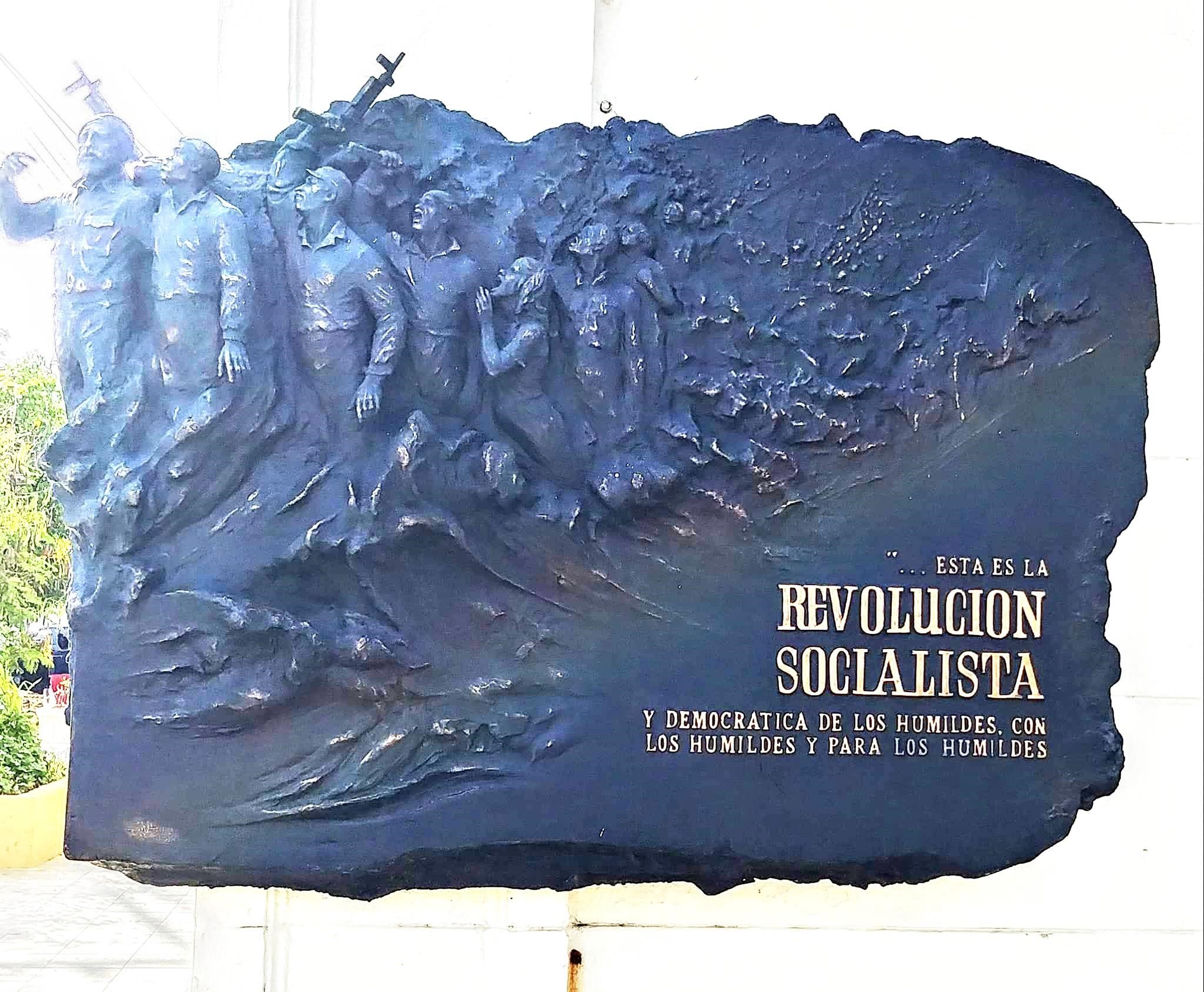

ON DECEMBER 20TH 2018, I spent eight hours touring the Cuban capital city Havana before being forced to evacuate by indiscriminate 15-foot high waves. My brief visit to see family coincided with preparations for the 60th anniversary of the Cuban Revolution (New Year’s Day 2019), which prompted me as an aspiring Marxist to take my own perspective on Cuba seriously. It is my hope that this reflection, comprising a mélange of history and anecdote, will serve the socialist with the patience for a critical perspective in the 21st century. There is no time like the present for the Left to reconsider the Cuban Question.

The Yoke of Spain

Claimed for Spain in 1492 by the Left’s favorite bogeyman Christopher Columbus, the 750-mile island became the gateway to the riches of the New World. Cuba has been the jewel of the Caribbean for centuries, a destination for anyone with an eye for goods and treasures plundered from mainland South America or a taste for Cuba’s trinity of precious resources: tobacco, coffee, and sugarcane.

Following the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804), which took from Caribbean commerce its most lucrative sugarcane producer, Cuba entered the world sugar trade by exploiting a hole in the market and African slave labor. Spanish-held Cuba’s richest trading partner in sugar was the United States. The end of the American Civil War in 1865 and the abolition of slavery in the U.S. shook Cuban society. Cuban slaves working the sugarcane fields looked with hope; their owners looked with fear. It was a white plantation owner that struck the first blow in favor of the emancipatory promise of wage labor in 1868. Carlos Manuel de Céspedes freed his slaves, called on all Cubans to revolt from Spain, and began the Ten Years’ War, culminating in a peace treaty with Spain granting reluctant and half-measure reforms, while Cuba remained a colony with slavery.

Thousands of Cuban rebels went underground, chief among them the poet José Martí. Martí raised money among the Cuban exiles in the U.S. and shipped weapons to Cuba in secret. When the War for Cuban Independence began in 1895, Martí died in the very first battle, but not before his poetry and his speeches roused the Cuban people to fight for their freedom. The war was a humanitarian disaster. Spanish generals sent peasants on forced marches, exterminated any resistance, and opened some of the first concentration camps. The Cubans’ last chance was to make overtures for intervention to their powerful neighbor 90 miles to the north.

The Yoke of America

The American yellow press made international scandal of “the butchers of Cuba” to prepare the public mood for military intervention. Meanwhile, a show of force was sent to Havana’s harbor, ostensibly to protect American commercial interests. You may remember from your middle school textbooks the sinking of the USS Maine in 1898, leading to the declaration of (and ultimately the end of) the war within the year.

In exchange for ending U.S. military occupation, the U.S. government demanded serious promissory measures. While Cuba finally realized its long-anticipated political independence, American capital had seized upon much of Cuba’s economy following the peace. As Cuba drafted its constitution in 1901, American politicians forced in the Platt Amendment, guaranteeing the U.S. could militarily intervene if their interests were ever threatened by a free Cuba.1

Without Spanish taxes and with American investment, Cuba’s economy boomed. 80 percent of Cuba’s exports and nearly everyone’s livelihood were tied to the sugarcane fields. With the lost lives in the War, the Cuban labor force experienced a shortage and so welcomed hundreds of thousands of immigrants from China, Catholics running from Germany, and unemployed Spaniards.2 The available wage labor in Cuba was an opportunity to be free, to become self-made. But Cubans still worried about U.S. domination, especially after the U.S. sent troops to dismiss the elected government in 1906 and appointed an American governor, who then gave lucrative contracts to American investors in the sugar and railroad industries. Complicit in this was the Cuban bourgeoisie, who partnered with the American businessmen. U.S. capital provided railways, telegraph lines, schools, stores, factories — things that Cuba did not have. The rapidly growing Cuban working class felt that their freedom was in crisis, and some fomented resentment around the imperialism that hung like the sword of Damocles over the Cubans’ heads.

Until now, Cuban sugarcane ruled the global market, but it had to compete with sugar beet production in Germany and Russia. Everything changed with World War I. Markets even larger than those of French Haiti opened up for Cuba amidst the turmoil of WWI. Prices of sugar increased ninefold. From the richest owners to the poorest workers, the whole island profited from the war in Europe. But when the war ended in 1918 and trade routes reopened, Cuba had a surplus it could never hope to sell and an economic collapse without any government willing to aid.

While Cuba still depended on the U.S. economically, the reverse was no longer true; America was finding sugar elsewhere. The threat that most worried U.S. interests was the Russian Revolution of 1917. With armies of desperate unemployed, Cuba seemed a fertile ground for socialism. Cuban radicals sent representatives to the founding congress of the Third International in 1919 while more moderate political leaders at home prepared for a future beyond its monocultural dependence on sugar. Gerardo Machado, a war hero elected president in 1924, promised to free Cuba from both the U.S. and from sugar. He promised alternatives to American control over infrastructure by providing “water, roads, and schools” through public jobs, and that the U.S. would be made to renounce the Platt Amendment under pressure of Cuban tariffs. Machado was immediately popular, having transformed Cuba into the most modern Hispanic nation and the envy of development everywhere.

But in 1929 the U.S. stock market crashed. Panic caused by the Great Depression forced Machado to restore law and order via paramilitary forces, raise taxes to pay back American loans, and to cut employment dramatically. Thousands of Cubans took to the streets calling Machado’s regime “tropical fascism”; several died and hundreds were arrested. In 1933, a portion of the army sided with the rebels. Machado fled, rebels stormed the governmental palace, and most of Cuba felt they had won a victory despite the military remaining in charge. That same year, an officer named Fulgencio Batista called for colored troops to arrest their white superiors and declared himself Chief of Staff of the military. He also appointed a favorite of the student protestors, Ramón Grau, as president. Together, Grau and Batista undertook a program of reforms intended to weaken American influence. Within one hundred days, Cuba had women’s suffrage, labor protections, and limits to the working day. American capital remained worried that socialism would find an audience in Cuba during the Revolution of 1933.

Batista portrayed himself as a son of the people. Having native Cuban blood and being from the Eastern (rural) half of the island brought him favor with the peasants. He knew to ingratiate himself with the working class by appointing Grau. And he appealed to the U.S. as a man of law and order, above politics, who could control the contending forces of society. Following the new labor laws, the U.S. demanded that Batista oust Grau: in 1934 after only four months on the job, Batista did, with the aid of the communists nonetheless, annulling most of the reforms and appointing a series of more conservative presidents. Batista gradually reintroduced all of those reforms and more, including health care reforms, land redistribution, and the ethnic diversification of the military and police. In 1934, a new treaty from Batista removed from the Cuban Constitution America’s right to intervene in Cuban affairs vis a vis the Platt Amendment. Batista won the presidency in 1940 by the votes of conservatives, liberals, and socialists, by guaranteeing a new Constitution and to fight fascism in Europe.

Batista retired in 1944 to Miami and was succeeded by Grau, who did little to stem the tide of unwanted American mafia flooding into Cuba.3 As the rich got richer, the Cuban poor grew in number and in unrest. Nine percent of the entire country was unemployed. In 1952 Fulgencio Batista returned to Cuba to run for president, funded by the millions received for turning a blind eye to the mafia. As the Cold War developed, Batista chose the U.S. and suppressed all his former socialist allies as “Soviet spies,” losing their support in the process. Rather than lose the election, Batista launched another military coup, bloodless and without protest because of the dissatisfaction with the previous government.

Universities — usually hotbeds of dissent against the government — produced young political activists like Fidel Castro. In 1947 Castro put on hold his law studies to train with armed groups fighting failed revolutions in the Dominican Republic and Columbia. He returned to a Batista-run Cuban police state that repressed all dissent through arbitrary arrests, torture, and assassinations. In 1953, Castro together with a small group of armed students stormed army barracks and were defeated. In exile in 1955, Castro met Ernesto “Che” Guevara. The two returned to Cuba with a few dozen men and aid from the American CIA to fight a guerilla war in the Sierra Maestra Mountains. Following a failed assassination attempt, Batista’s unpopularity was manifest. The U.S. put an embargo on the island, and in response, Batista nationalized U.S. oil refineries and other U.S. properties. Finally, Castro’s band of rebels forced Batista to flee in 1959.

Castro drew his support primarily from the petty bourgeois elements (mostly peasants) demanding land reform. Castro amassed support from a motley crew of liberals, socialists, and conservatives. His early intentions were vague and broad and (as Castro admitted in the spring of ‘61) were nothing like the “Marxism-Leninism” that he later professed. His closest comrades said that Castro was pushed into the arms of the USSR to survive a U.S. invasion. The first declarations of socialism came years after the Revolution of 1959. As the Spartacist League quipped about Cuba in the ‘60s: “[W]e are still confronted with a very queer animal — a “workers’ and farmers’ government” in which there are no workers or farmers and no representatives of independent workers’ or farmers’ parties!”4

The Cuban left was without a class-conscious and combative proletariat that could polarize the petty-bourgeois militants, drawing some to the workers’ side and repelling others back into the arms of the bourgeoisie. The Socialist Group of Havana formed in 1905; they split over the direction of the Russian Revolution in 1917. The Communist Party of Cuba was founded in 1925 by Moscow-trained members of the Third International (Comintern). For three decades it adhered to the Stalinist line while also collaborating with Batista, its members even being rewarded with government positions.

The Castroite Revolution happened through a popular, patriotic upsurge of undifferentiated Cuban masses. Throughout, the working class failed to challenge for power more than once. The Castro regime displays the indeterminacy of Bonapartist politics,5 the tension of either the potential to regenerate and consolidate a capitalist state or for a section of that regime to seize power solely for the working class. This was Karl Marx’s lesson from the failure of the revolutions of 1848: that the proletariat is the vanguard of the battle for society. The political independence of the working class is paramount to achieving socialism.6 In the absence of independent working class leadership, class struggle is abandoned in favor of sating the discontents of other contending classes (e.g. peasants, petty and big bourgeoisie, etc.). The defeat of the working class portends the common ruin of all classes.

Tragically, an organized working class never even existed in Cuba to be defeated. Castro, not unlike Batista and Grau, suffered the historical burden of self-preservation; Cuba now tails the larger capitalist world all because the Cuban proletariat never seized the task set for it: the direct intervention into society on behalf of the whole working class. The existence of a mass socialist organization never manifested — a failure from which we all still suffer.

Cuba has a 500-year history of untapped potential and unfulfilled promises. Pick your preferred jumping-off point for when any hopes of an emancipatory Left died. Was it when the bourgeois radicalism of wage labor failed with Céspedes’ rebellion? Was it when Martí’s internationalism and his hopes for a Latin American republic died with him on the battlefield?7 Was it when the Left capitulated time and time again to Batista and Grau’s pacifying reforms? There were many chances for the Left well before Castro took power. The seeds of everything Castro did were sown much earlier by other Bonapartist leaders. Modernization, land redistribution, national independence — these reforms are most certainly not socialist tasks. Why is Castro’s “radicalism” even a subject of speculation on the Left when he is indistinguishable in deed from the people he displaced? It should go without saying that Castroism is necessary in some sense and cannot be blamed for Cuba’s situation. But hope should remain for the self-critical leftist that the historical need Castroism meets could be met in alternative ways.

Many in the New Left looked to the Cuban Revolution as a world-historic event, even going as far as pronouncing the ersatz “Marxism” a development upon orthodoxy. But Cuba was merely one more domino to fall in the chain of national liberation movements that proliferated following the failure of international socialism in 1917. “Decolonization,” “anti-imperialism,” “self-determination”: throw your favorite dart from the Left’s cornucopia of counterrevolution, and you are bound to hit an example of history repeating itself. The defeat of the working class in 1848 left the reactionary elements to deal with the same problems but with less adequacy; so too did the defeat of 1917. The 20th century is the century of petty bourgeois and peasant bases of support masquerading as socialist. Cuba is just one interesting case study for the decline of the Left in the 20th century.

The Yoke of the Left

Cuba’s freedom still suffers from the diminished expectations and lowered imaginative horizons that plague the Left. The state motto is “homeland or death, we shall overcome,” betraying a strong nationalism. It also betrays a real opportunism and a denial of reality, as if the struggle continues, as if the revolution is on-going, as if Cuba would be socialist tomorrow if not for those pesky capitalists. The Left’s perspective on Cuban Communism, or “sugarcane Stalinism,”8 strikes a woeful resemblance to the Left’s perspective on the original. Cuban Communists, like their Cold War ally, are the organizers of defeat. The leaders must strike the best deal in order to protect their racket (because they can never really push the revolution forward), and in this regard they have done well. Even under the crushing weight of the U.S. embargo, Cuban healthcare and education are world famous.

But as the Left lines up to praise these “accomplishments” in a hurry to worship the god of the established fact, they lose sight of their pacifying effect. Even now these “revolutionary gains”9 are being questioned and/or annulled via constitutional reforms and public opinion shifts. The reverence surrounding 1959 is fading; the 60th anniversary passed without pomp or circumstance. With trepidation, and to preempt the pessimists of the Left who can only find salvation in the Third World, I echo again the Spartacists in the ‘60s: “Certainly the massive enthusing over Fidel Castro by those with pretensions to revolutionary Marxism has been today largely dispelled, or more generally, displaced. But the explanations, rationalizations and substitutes of all the centrist, revisionist and reformist currents have been no improvement.”10

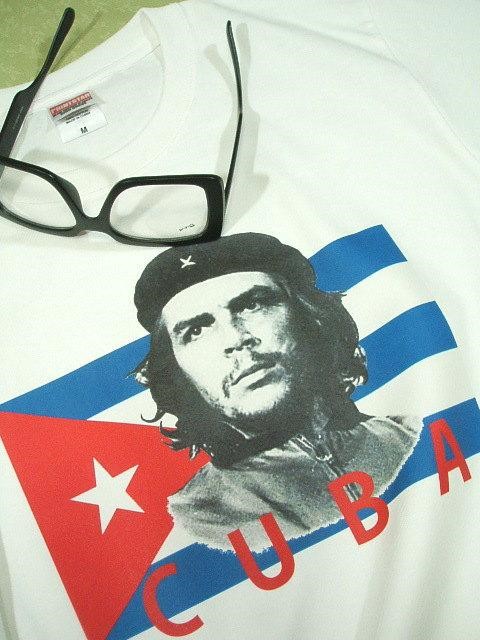

Cuba is changing. The myth that Cubans have apotheosized Castro and Che is just that; MAGA hats and #ImWithHer bumper stickers in America outnumber any Cuban leader icons by a wide margin. Only the government buildings and the occasional street art piece venerate old revolutionary names and faces. Polls show — and my personal experiences confirm — that absent of any real faith in a socialist future, Cubans want American investment to return. They want their infrastructure rebuilt and the commercial goods to splash like waves onto their beaches, and they will sell you all the cigars, rum, and coffee that it takes for tourists to pump money into their desperate hands. What leftist among us could turn down a Che t-shirt for sale?

Today on the Left there remains the impulse to declare Cuba to be one thing or another e.g. “actually-existing socialism,” a “degenerated workers’ state,” “bureaucratic collectivism,” etc. rather than what it is — an open-ended question. The orthodox Trotskyist position of the Spartacist League reminds us that “we make no contribution to Marxist theory or to an understanding of the Cuban Revolution if we start from the idea that before we can support a revolution we must baptize it “proletarian,” or if we are looking for non-working class shortcuts to socialist revolution. Above all must we abjure the tendency to think in abstract categories, to seek before all else for a tidy ideological pigeonhole into which to cram an unruly reality.”11

I know you want to ask “What is Cuba?” Is it a workers’ state or is it not? This question side-steps the task. The affirmative renders action unnecessary; the negative renders it impossible. Rather, Cuba is both and neither. The situation displays multiple potentialities. The task remains for the Left to actualize the desired reality. It is too early to answer in terms of finished categories, for the nature of the Cuban Revolution cannot be decided by theory alone.

What is to be done?

Domestically, a profound political change in the form of workers’ control is necessary. This is only possible through the formation of a disciplined party representative of the whole working class i.e. the international working class. The present administrative apparatus in Cuba must be replaced with peoples’ institutions. The petty-bourgeois and big-bourgeois elements in Cuba must be made to step aside for the vanguard of world history.

But the Cuban Question will be answered outside of Cuba. The Cuban “solution” of Castroism was imported by other Latin American countries for even less revolutionary, more disastrous results in the 20th century, so doubly necessary will it be to export a genuine internationalist socialism to Latin America in the 21st century. Cuba’s fate is bound up with that of the world revolution, and the entire continent is a few paces behind the starting line.

Owing to domination by American capitalism, Cuba is a drop in the Atlantic Ocean. Cubans, even with the proper revolutionary will, could not shake capitalism before or now. International revolution failed Cuba; we must never let it fail again. In all sincerity, Comrades Castro and Che must be redeemed. Cuba is equally naively and optimistically viewed as a long transitional state, despite their own contestations to have arrived after the “Triumphant Revolution.”12 Are they holding out, waiting for reinforcements? Then by all means it is time to incorporate them into a global socialist order, to be able to say no more that the revolution has stalled or been marooned.

If we say that the final sentence as to the Cuban Revolution will be passed on the world-historical scale, this is not to counsel passivity to the Cuban left. There is still room for progress toward the establishment of an authentic workers’ democracy through the organization of the Cuban masses. But our comrades in the Caribbean cannot become free on their own.13 Internationally, there is no Left in existence capable of thwarting U.S. imperialism with anything beyond empty phrases. Therefore, the task most pressing for Cuba generalizes to the United States. Our responsibility is at all times to discuss the situation clearly and critically, and without any fetishism. We must criticize openly and frankly the mistakes and inadequacies of that leadership that prevents the revolution from spreading hemispherically. Ultimately the problem plaguing Cuba is a problem shared the world over: lack of a mass socialist party guided by genuine Marxist leadership.

The salience Marx retains for the 21st century must be his ruthless criticism of the socialist movement itself and the higher consciousness attained thereby. If Cuba still matters for the Left today, then it is because 1848 still matters. We must discover what tasks the Left has cast aside, return to them, and this time master them. The way forward begins by acknowledging how backwards we are. The precondition for progress in the Revolution is first admitting the deep regress wrought in the name of the Revolution. The time is now for the Left to sober up from the Cuban rum it has thrown back. Only the Left’s best mutineers can leave the counterrevolution behind to roast in the hot Caribbean sun while they set sail to join their comrades in pursuing a socialist future. One day the Left will take up Marx’s old slogan of the revolution in permanence to make good on Che Guevara’s oft-quoted call to arms: “¡Hasta la victoria siempre!” (“Until victory, always!”) | P

- All eight stipulations were accepted despite protest, with one allowing for military bases. Between Guantanamo Bay and the Panama Canal, the U.S. controlled all shipping between the Atlantic and the Pacific.↩

- Angel Castro, Fidel and Raul’s father, was one such immigrant from Spain. He made his riches working as a manager for an American plantation in Cuba.↩

- U.S. prohibition from 1919 to 1933 made Cuba a destination for saints and sinners both.↩

- Spartacist League, “Cuba and Marxist Theory,” Marxist Bulletin No. 8 (New York, 1966/1973).↩

- Bonapartism is an inverse expression of proletarian socialism. In the interregnum between when the bourgeoisie can no longer rule and the proletariat cannot yet rule, Bonapartist politicians balance the contending classes. See Karl Marx, The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, in Marx-Engels Reader, ed. Robert C. Tucker, 2nd ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, 1978), 594-617. Available online at <https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1852/18th-brumaire/>↩

- See Marx, “Address to the Central Committee of the Communist League,” in Marx-Engels Reader, ed. Robert C. Tucker, 2nd ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, 1978), 501-511. Available online at <https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1847/communist-league/1850-ad1.htm>↩

- See: <https://thepioneeronline.com/34435/study-abroad-cuba/essays/patria-o-muerte-anti-colonial-history-and-cubas-place-in-latin-america/>↩

- See: https://intransigence.org/2018/07/09/sugarcane-stalinism/↩

- See: <https://www.marxist.com/cuba-40-years-on-defend-gains-of-revolution.htm>↩

- Spartacist League, “Cuba and Marxist Theory.”↩

- Ibid.↩

- See: <https://thepioneeronline.com/34435/study-abroad-cuba/essays/patria-o-muerte-anti-colonial-history-and-cubas-place-in-latin-america/>↩

- Nor can we! Nota bene.↩