What was the Socialist Party? An interview with David McReynolds

Erin Hagood & Stephanie Gomez

Platypus Review 110 | October 2018

On June 4, 2018 Stephanie Gomez and Erin Hagood of the Platypus Affiliated Society conducted an interview with David McReynolds. The interview was broadcast on an episode of “Radical Minds” on WHPK 88.5-FM Chicago. David McReynolds was a key figure in the Socialist and Pacifist movements in the United States throughout his life. He passed shortly after this interview was conducted in his apartment in New York. What follows is an edited transcript of the interview.

Erin Hagood: Could you tell us briefly about your political history on the Left?

David McReynolds: I have been active in the socialist movement since 1951 when I joined the Socialist Party (SP), ran for President twice on their ticket, and ran for Congress and for Governor, but I resigned from the SP a couple years ago. I do belong to DSA and to a group called the Committees of Correspondence. I also joined the pacifist movement in 1949. I have been active in that and worked for the war resistance for about 40 years until I retired in 1999.

Stephanie Gomez: When did you join the DSA?

DM: That is a minor funny story. I joined it some years ago. There was a multi-split in the Socialist Party. It split three ways in 1972. One group headed by a guy called Max Shachtman, who's now dead and was very right wing, was the Socialist Democrats. That has gone out of business. That was one third. One third followed Michael Harrington, and set up the Democratic Socialists Organizing Committee, which became the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). The third group kept the old name and became the Socialist Party, which we organized in ‘73.

Anyway, there was a motion at one of the SP conventions way back then to make membership in DSA incompatible, which I thought was silly. I did not agree with Harrington. I thought he was wrong on the issue of Vietnam, but I also thought it was just silly to make it incompatible. I said okay, I am going to join DSA and if you want to expel your candidate for President, you can do that, and I joined, sort of... Then I kept up the dues over the years.

I am very excited by the shift recently in the growth of DSA. It is really significant now, but I am just a nominal member for many years.

EH: Why exactly did the Socialist Party split up into those different groups?

DM: The Socialist Party, which was the inheritor of Norman Thomas, or inherited his tradition, had really sort of come to the end of the line during World War II. The Communist Party grew during that time because the U.S. was allied to the Soviet Union, so it made joining the Communist Party sort of respectable in an odd kind of way. That stopped very soon after the war and the McCarthyist period began, but there was a time when the CP was fairly strong. But the SP had a mixed position on World War II. The pacifists in the SP didn't support the war, others did. The great surge of American radicalism really ended with the war. But the war, which is hard to understand now because we're living through so many wars, World War II was an extraordinary event, a kind of total war that everyone was involved with everywhere in the country unless you were opposed to the war, and that was fairly rare. There really were no groups of dissent. The Communist Party behaved. The SP was quiet. It had really been quite significant in this country with a large membership and Norman Thomas as a spokesman, but it never regained its strength when the war ended in 1945. Now we thought at the time, as you'll find out being young, that you often think where you are now is where you're going to go. And so, we were thinking in 1950-51, that we were joining a group that was really the same as the one that had been so large. We did not realize that it was diminishing and sort of vanishing.

I worked at that time—because the SP was so small, maybe a thousand members—to bring in a group called the Independent Socialist Committee, which was a reformed Trotskyist group, which claimed that it believed in democratic socialism. And I thought that if we brought them in, we could bring in many of the kids who were going to the New Left and did not have a home who eventually ended up in the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). My hope was to create a political home and to bring in the people leaving the Communist Party. There was a major split in the Communist Party at that time over the speech by Khrushchev to the 20th Congress of the Communist Party in the Soviet Union in which he admitted the Soviet Union had lied, that their record was terrible. This had a devastating impact on the worldwide communist movement. Sort of like being told after you've worked with your computer, and the computer suddenly flashes a note saying you have been off on everything that I have said by ten digits. What do you do? You thought this was total truth and suddenly nothing—it is very shocking.

There were splits in the communist movement and I helped to bring some of those people into the SP. They weren't bad people, but what happened was that Shachtman had his own view of taking over the SP, which he did, and that came to a climax in 1972. By then, I had resigned because the party had given critical support to the Vietnam War, which I thought was impossible. But that was Michael Harrington's position, and I thought it was terrible, so I resigned in ‘71.

But there was a convention in ‘72, and at that convention Shachtman had a majority and he changed the name from Socialist Party to Social Democrats U.S.A. Harrington had been out-maneuvered, and he split to form the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee which became DSA, and those in the left wing and the old guard reorganized as the Socialist Party in 1973. So the reason for the three way split was the fact the modified Trotskyists had taken over the party with a very conservative point of view. The better element of Max Shachtman’s people left and almost all of the old guard left.

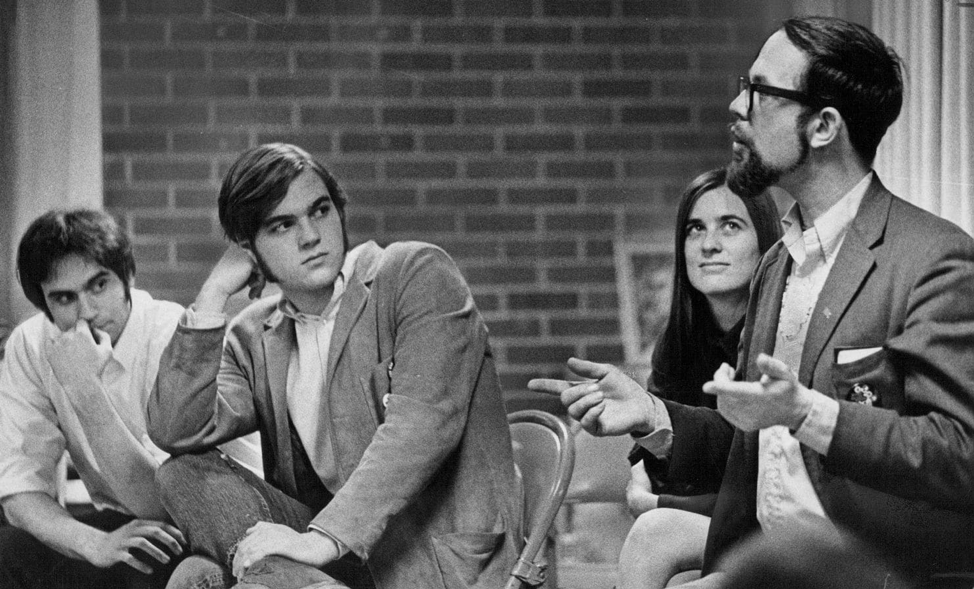

David McReynolds, right, in 1970, explains plans to protest the draft to a University of Denver group. (Denver Post via Getty Images)

EH: I am interested in what you said about with the New Left. You wanted to make a home for the New Left in the Socialist Party. I think that often when people talk about the New Left there's this idea that it was a high-water mark for leftist politics. At the same time, from our perspective now, it does seem to be part of this gradual decline of the Left. What was the significance of the New Left? Were there gains? Do you think that there were missed opportunities?

DM: If you go back to that period, the Old Left was really finished. The Communist Party after the Khrushchev revelations had lost their magical power. The Soviet Union was no longer in charge of all the communists in the world. There had been a split in the world movement between China and Russia. At the same time, the old left really had disintegrated. The SP was pretty much gone, the CP was shattered, you had this extraordinary wave starting in 1955 of the civil rights movement. Bayard Rustin, who was my boss at the time, I worked under Bayard for some years, Bayard made the point—and it was a very good point—that the American society at that time, in the early ‘50s under Eisenhower, was stagnant, calm, there was no movement. The Cold War was proceeding without objection. Segregation in the South was there unchallenged and suddenly, if you think about a piece of steel, like one inch thick and ten feet wide, and someone hits it, it vibrates everywhere, and that's what Montgomery, Alabama did. It shook up all of American society.

People in the North felt, "Well, if they could do this we can do things." So there was a movement in the civil rights movement in the north. A similar movement was organized against the nuclear testing. You had a general sense of vibration that was happening. But the New Left was made up of kids who had no adult group to go to. We had failed them, and so they formed SDS. They were very, very important. They organized the first large scale demonstration against the Vietnam War in 1965.

Tragically, they were divided and shattered by the effort by the Maoist group to take control, and with a very sectarian line, and it destroyed SDS. Its split among other things, it ended up with the... what am I thinking of? The...

EH: Weathermen?

DM: Well they're underground. That as a very left-wing group, and it effectively destroyed the New Left, but it had been a very powerful group.

EH: What do you mean when you say that you all had failed the New Left?

DM: Well in the 1930s, if you were a young person, you could join the Socialist Party or you could join the Communist Party. There were two well organized adult groups. But by 1960s those groups didn't exist, so if you were a young person, where did you go? The sense of direction and meaning is lost, and you were left with the New Left, you were left to find your own way.

EH: Obviously you had McCarthyism and the crack up of the Communist Party intervening in that period leading up 1960’s, but do you think that there was some way that those organizations could have weathered that period?

DM: No. They were burned up, and that is leaving aside a discussion of the Trotskyists who were not relevant despite their damage to the Socialist Party. There were at least two problems. One was that the Communist Party and with it all groups that take a Leninist position or a Trotskyist position believe in the vanguard theory. And the vanguard theory is, there is one party or one group that is leading the mass of people. There cannot be two vanguards, only one vanguard. Any other group which is saying that it is leading the struggle is the enemy and must be attacked. There can be only one vanguard.

The CP and all the Trotskyists, infamous with a number of multiplications of Trotskyist groups, are all fighting for the role of the leader or the vanguard. That was a fatal mistake by Leninist movement. The Socialist Party was really haunted by anti-communism, not from McCarthy at all, but from our experience back from 1917 when the split occurred between the Socialists and the Communists. It was a very bitter split. I do not think you can grasp from here how damaging anti-communism was. We had been united and struggled to overthrow capitalism, but the nature of what happened in the Soviet Union was so terrible that it made any attempt to defend the Soviet Union impossible.

On the other hand, there are certain historic inevitabilities about what happened in the Soviet Union. After the revolution occurred, there were two views. Trotsky had one and Stalin another. They were both right in an odd way. Stalin felt there could not be a world revolution at that time. And he was right that what you had to do was to defend the worker’s state, the first worker’s state. That is my class, and that meant industrialization, building up a military machine and changing Russia from a peasant economy to an industrial economy.

Trotsky argued for a world revolution and said, "If you focus only on Russia, you're going to have a militarized dictatorship isolated from the world." And they're both quite right. Trotsky's analysis was absolutely correct. But a world revolution was not possible, and there he was wrong. Stalin was right that the worker’s state needed to be defended, but inevitably became, well, Stalin. Both groups had been really destroyed by their internal contradictions.

The Soviet Union did some good things. I think it is very hard for Americans to have any grasp of what World War II meant. There were about 27 million Russians who died in that. One out of every ten Russians was killed. And that leaves you with a large number of wounded that become a burden on society, of orphans who lost their parents, and of women who have no husbands. It's very hard to conceptualize what life is like in 1946 when the war was over. And the war had destroyed all of Russia from a line from Leningrad in the north, through Moscow, down to Stalingrad and everything west of that was destroyed. Every factory, every airport, every dam, every railroad station, all the housing was destroyed. We have never really grasped what the war meant to Russia. This does not justify Stalin at all, but it is important to see that.

I am not defending Stalin, I am trying to explain the complexities. Stalin entered the Hitler-Stalin Pact, for example, because the West had turned him down when he went to the West and asked that they would form an alliance against Hitler, and they said no. Stalin, having been turned down by the West, then signed the infamous Hitler-Stalin pact. We did not really give much alternative to him. I am just explaining how tragic life was in a way, and Stalin certainly was barbaric, but the hatred of what he had done could demoralize people who should not really have made that their life's work, anti-Stalinism.

The SP had been destroyed by anti-communism, and the communist side had been hurt badly by the vanguard theory. At UCLA, when I was a student there, the CP cell put out word that the kids should not come to my apartment down by the beach because I worked for the FBI or the Dean's office. I mean, that was really sort of nasty. Once, a couple of kids who had been in the CP joined us when they realized that the communists were not for artistic freedom. They thought I was too anti-communist, and I was. They felt I ought to get to know them and they took me to a party that the communists were having. It was full of young people like yourselves. Well, within 20 minutes of my arriving, the party ended. Everyone got their coats and left, because they were afraid to be in the same room with someone who was clearly working for the FBI. Do you see the paranoia on both sides?

I had a struggle which I think I won, mainly because I am a pacifist, but it is worth telling the story. We had a student group of young pacifists, and Dorothy Healey, who was the chair of the Southern California Communist Party and had been one of those indicted under the Smith Act, but not jailed, had come to our youth and said she wanted to have a discussion between the CP and the young pacifists. They come to me as the elder statesman and asked what they should do. I said, "Well, tell Dorothy, yes, we'll have that discussion, but tell her they'll have her speak for their side, because you will see that she will not agree to the discussion." I was wrong. She agreed. We had the discussion in a basement in Pasadena, about 20 people on both sides, and they didn't say anything, peace and a friendship, nothing political. But one of their people called me a couple days later and said they had not realized that we believed the things that we had talked about and they would like to have another discussion. I said, "Okay, but you have to say something. You can't just say peace and friendship, and maybe it would be easier if just two or three of us met so you do not feel that you are exposing people." And he agreed.

We met with Dorothy Healey and the editor of the Communist Party Weekly, and a Quaker, a fellow member of the SP, and myself. In the discussion my fellow socialist talked about the need for civil liberties for everyone, including Joe McCarthy. And Dorothy turned to the, one of those with us who was a quasi-Trotskyist and said, "Ted, I understand why they believe this, because they're bourgeois, but you are kind of a Marxist. How can you defend freedom for McCarthy?" And I relaxed because it was the first honest word I ever heard from the communists in all those years. Dorothy and I became friends and I helped set up a meeting, a debate before I left California. I got to be on good terms with some of those in the CP up to their split in the end of the 90s.

While I was not immediately part of the split in 1917, I certainly was a party unto it and affected by it, and damaged by it. Both sides were damaged by preconditions that were set, starting way back in 1917.

EH: So, what about Marxism? I ask because so many characters in this story are taking up different strands of Marxism. Do you think it was a good thing, a bad thing? Is there a place for Marxism?

DM: I am a Marxist, a democratic Marxist, but I am not well-read in Marx. I never read Das Kapital. I have picked it up from the people I have followed. I do believe that the material environment shapes our consciousness, that if you are born into poverty, your views of life are shaped by that. If you are born in Japan, your views of the world are shaped by that culture. I believe that people are not as such free agents as they think. They are shaped by the material environment. And I think that whoever controls the means of production does control the society. How you manage to transfer that to a social ownership is very hard to work out.

However, I am not a scientific Marxist. I think scientific Marxism is nonsense. If you look at the social movements, they were eager to be called scientific. They did not want to be considered just ordinary movements. You have ‘scientific’ socialism, you have... political science was not a science at all. You have sociology, which is not a science, but it goes by that name. None of those are real sciences. They cannot predict the future precisely. Marx chose that word to define his movement as opposed to the utopianism that had come before him. And on that I agree with Marx. I think Marx is very wealthy in terms of ideas. He is a major intellectual power in the world, not just in the West. I just regret that people became too attached to the idea of scientific Socialism and overlooked some of the humanist aspects of Marx's early writings.

I think the movement is healthy if it has a good number of people and they have some idea of what Marx was talking about. Not an orthodox Marxist, but some idea. But I do not think everybody has to be a Marxist, and a strong movement can be built with lots of different views—Christian, Judaic, Buddhist.

EH: In a letter Marx writes to his friend Joseph Weydemeyer in 1852, Marx says that his one original discovery is the dictatorship of the proletariat. Do you think a party is useful for making Socialism? Do we need the dictatorship of the proletariat?

DM: Yes and no. First, we do need an organizing force. A socialist party or a socialist movement, if it is not too dogmatic, is very crucial for holding people together and directing the struggle. We are up against the state, the CIA, the FBI, the organized power of the Koch brothers, and so on. We need a movement, and that is a party or an organization. It does not have to run candidates.

But Marx, by dictatorship of the proletariat, was not talking about what Lenin ends up adopting. He meant, and it was a bad choice of words on his part, that up to that point the ruling class, even if it had a democratic façade, was really a kind of dictatorship of one class. Workers did not control the press, the radio, television. Those were run by people with money. You cannot start a newspaper if you do not have money. What you had is what can be called a dictatorship of the middle class. Free, yes, but not that free. You try to exercise that freedom and you see how fast the limits are put down on you, what you face in terms of legal restraints. But he said that the dictatorship of the proletariat would be more democratic, broader based. It meant the workers would dictate the politics, and he did not have in mind what Lenin set up, which was an actual dictatorship with a police force. That was not what Marx had in mind. There is a lot of confusion about what he meant. But he did mean that there would have to be a willingness to prevent the middle class from regaining power.

EH: You brought up that there does need to be a party or organization. I was wondering if we could talk about the DSA. What is the difference between a party and an organization? What kind of organization are you talking about and is the DSA similar to what you have in mind?

DM: Party means the organized center of a movement, whether it runs candidates or not. DSA would fit my definition of a party, although I think it is not going to run its own candidates. DSA is formed these days by the kids who were involved in the Bernie Sanders campaign. They found a new place to go in the DSA, and they may eventually decide to run candidates. You can decide to run candidates in some areas and not others. Here in New York, the lower east side, where I ran for congress a couple of times and got 5% of the vote in ’68, it was the height of the Vietnam War, so it was possible to run a political campaign, we had no thought of winning the election at all. At the same time, I found in this area where we lived that the city council person was in the Democratic Party. She was for many years a communist working through the Democrats. Very militant, always a lone wolf. She lost an election because we did not work for her and got a Republican. We found out, under Giuliani, how dangerous it was to have a Republican in the race and so we later supported the Democratic candidate for city council who was a Puerto Rican lesbian and probably came out of the Puerto Rican Communist Party. And it is a left seat here, which means the Democrats win. In some cases people on the Left have supported Democrats, in some cases they run as independents, and in some cases they do something else entirely than run in an election.

EH: When you see young people today who are in the DSA and call themselves socialist, do you think they are in the tradition of the SP, of your work?

DM: I do, I think they are part of a tradition of democratic, organized alternatives.

EH: Do you see any differences between the way you organized back in the SP and how socialists are organizing today?

DM: Yes, I think the SP was fixated on running candidates. I think one of the problems we have got in this country, and I have never worked it out myself, is that the country really is a two-party country. Minor parties, and I am old enough to have seen many, have all been defeated. You can look at everything from Teddy Roosevelt to Debs. All of them, without exception, have been defeated, have not been able to build an ongoing national structure. Every time they thought they could build a new, third alternative. Every time, they have ended up going to the Democrats or Republicans. This is because the moment a movement gains strength, the Democrats or Republicans will adopt its key points to win them back. We are stuck with that in an odd way. Even though they are very different, even though the two parties are in fact more than two. In the Democratic Party under Franklin Delano Roosevelt, you had the southern Democrats who were racist, not to mention segregationist. And in the north, you had the big-city Democrats and the trade unions. They combined to run the country for all of FDR’s time. Half of them racist, violent segregationists and half of them progressive in the same party. You really had two parties: a southern and a northern party. The Republicans also have the moderate Wall Street people in New York and the East Coast and the fundamentalists that you find in the Midwest or the mountain states that back Trump. They work in the framework of the Republican Party.

EH: Do you believe the DSA has been or will be able to avoid this dynamic where different movements that you see as challenging, for example, the Democrats get sucked back into the two parties?

DM: They could. It depends on how mature their leadership is, how much they can avoid infiltration by small groups that want to take control of DSA, which see DSA as a good thing if only they could take charge of it. They need to maintain a broad outlook to do this, and I do not know if they can. I hope they can. I have been very impressed with the DSA kids I have encountered here on the East Coast.

EH: You discussed earlier that it will be necessary to take state power in order to make the revolution against the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie. There is a common view that would say this means winning elections. However, you have stressed that it is not necessary for a party to run candidates. How would a party take power in other ways besides electoral politics?

DM: It would help if you go back and look at this country before the Russian Revolution. One of our problems on the Left is that everyone keeps thinking about October 1917. Where it went wrong or where it was right. And they forget that there was a mass democratic, socialist movement in this country under Eugene Debs at the turn of the century, about 1900, through 1917, when they had the international split with the Soviet Revolution. That was a mass, American party. We had no foreign examples to guide us. We should go back and look at that, both the weakness and the strength. We thought then that we could build a third party, that was the whole point. Turns out that is harder to do than we think, but you can certainly build local groups. You can win members of congress and hold on to those seats. If you think about the SP in Milwaukee, we had the mayor from 1948 to 1960. Frank Zeidler was not a revolutionist. He was a socialist, but not a Marxist. Frank was the mayor of Milwaukee for three terms at the height of McCarthy, so he proves you can do it. He had no national party to back him, the party in Wisconsin was its own thing. It couldn’t continue after him because times were changing.

EH: So why did the old Socialist Party fail? Do you believe it was a mistake for the Socialist Party to be a third party? There was also the split that occurred in 1917 after the Russian Revolution. Eugene Debs himself at the time said that he was a Bolshevik, but many in the party disagreed with him.[1]

DM: Looking back, there are lots of reasons for what happened, not just the division between the Socialists and the Communists in 1917, but the fact the Socialist Party opposed World War I. World War I was a very popular war, it may have been the most popular war we ever fought. People did not play Bach or Beethoven because it was German. Sauerkraut was called “Liberty Cabbage.” It was a whole weird identification with a total patriotic war to end all wars, to make the world safe for democracy. I think the Socialist Party lost some appeal because it really had opposed the war. Our people went to prison because of it, including Debs. While that is a great part of our history, it also did not help us win a lot of people. Plus, the Russian Revolution led to the kind of McCarthyite phase of 1920-21, when the Palmer Raids occurred. I do not think you can blame it on the party, you have to look at the context. I think Debs decided by the end of the ‘20s that we needed a labor party, not a socialist party. You ended up with Norman Thomas, a one-man ruler, in a sense. Not really the leader of a mass party.

EH: What advice would you give to someone who wants to make socialism today?

DM: I think you should read the Debs biography, The Bending Cross, which is a good biography of Debs, not dogmatic but very moving. There is a wealth of literature in the socialist movement, I would ask someone academic what they would recommend. I would be very cautious of groups with a Trotskyist tradition. I have found them very difficult to work with and inclined to split over the slightest agreement to have a perfect line, and you’re never going to have the perfect line.

SG: Do the Trotskyist groups still tend to split all the time?

DM: Yes, they do. If there is a parallel, it would be in the Christian church, where for all the folks in the Catholic church, there was really just that one split of Luther. The Catholic church has remained steady, unified. It has been there for a thousand years, it is still there, ups and downs, good and bad, corrupt and saintly—it is there. But Martin Luther, in breaking, set in motion the concept that it was okay to question the authority of the church, which meant you could question Luther. If you look at the Christian faith, there are a dozen division within Christianity which were possible because of Martin Luther’s split with the Roman Catholic Church. The Trotskyists tend to take that position literally. If you can break with Moscow, which they did—very courageous of them, they deserve a lot of credit for that—everything is up for grabs and you lose sight of the importance of maintaining a united movement. You really have nothing else. We have no army, we have no newspaper, we have no radio, and it is very important for us to have a comradely sense that dominates the movement rather than search for the perfect answer. There is no perfect answer, and the Trotskyist groups will keep on splitting forever. There are maybe two dozen international Trotskyist movements today, which is silly, but they are there and they will keep on splitting. And they will carry that into any group they go into. They will try to seize the leadership of the group to make it the vanguard group.

My life experience has been that the communists are easy to work with compared to the Trotskyists. The communists have a good sense of the mass and the Trotskyists do not, and I do not either. I remember we had a meeting once to discuss how to organize to fight the raising of the subway fare. And I said we ought to organize a campaign around a no-fare, free subway, but an old guy present said, and he clearly had to be either of the Communist or Socialist Party because he said, “No, you can’t say free subway, people will think you’re nuts. You can say don’t raise the fare, they will understand.” He grasped immediately what made a mass movement possible, a demand that was achievable, not a demand that was perfect, good, right, but an achievable demand, do not raise the fare, whereas my position was to abolish the fare. Great position, but everyone who was working for a living and scraping to get by thinks, “Well, I don’t have time for that. I want to keep the fare as it is.”

Where is the mass of people? What are they going to put up with? And the old communist and socialist movements had a good sense of the mass. The Trotskyists don’t have that sense, they tend to look for more perfect, correct, idealistic, utopian solutions. And there is a paradox because we need to have the utopian solution put forward within the movement always, but it is not an immediate demand.

EH: How do you connect these immediate demands that the utopian demands?

DM: Very hard, that is up to you to work out, I have no idea. I am throwing it back at you. There is a value to the radical position. I came out of the War Resisters’ League and the pacifist movement, which is based on absolute values and absolute resistance to military service, for example. I think that that movement has a very important, prophetic role to play. In that sense, the utopian must be respected. |P

[1] “The Day of the People” (February 1919), written about the assassinations of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg during the Spartacist Uprising of the German Revolution, available online at <https://www.marxists.org/archive/debs/works/1919/daypeople.htm>.