Slavoj Žižek, Donald Trump, and the Left

Leonie Ettinger

Platypus Review 99 | September 2017

A CHANNEL 4 NEWS INTERVIEW with the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek circulated on the internet during November 2016, just days before the U.S. presidential election. In the video, the leftist philosopher appears in his usual manner—twitchy, repeatedly rubbing his nose—as he answers the question as to who would win his vote if he were American. Without hesitation, Žižek belts out, “Trump!” Then he elaborates: Trump is not the better candidate, or even likable, but Clinton poses the threat of absolute inertia. Conversely, Trump’s intervention could productively disorder the American two-party system: “If Trump wins, both big parties, Republicans and Democrats, would have to return to basics, rethink themselves, and maybe some things can happen there,” Žižek opines. “That’s my desperate, very desperate hope—that if Trump wins, it will be a kind of big awakening, new political processes will be set in motion.” Aware that a possible Trump presidency scares liberals, he acknowledges the dangers in Trump’s cabinet appointments, and tries to give his listeners some perspective: “America is still not a dictatorial state, he will not introduce fascism.”[1] To Žižek, Trump is not simply the lesser evil. Rather, unbeknownst to the presidential candidate, the disarray he would create in the party system could prompt the Left to rethink and to organize around a politics that points beyond the failing neoliberal order.

As might have been predicted, the video caused an uproar among Žižek’s mostly Leftist followers. How could a self-proclaimed Marxist publicly endorse a Republican, who had been widely described as a fascist,[2] bigot,[3] misogynist,[4] and an immigrant hater[5]? Noam Chomsky compared Žižek to those intellectuals that tragically welcomed the rise of Hitler as a potential vehicle for social change, only to be persecuted shortly thereafter for their religion, culture, or politics.[6] Elsewhere Žižek was called irresponsible,[7] an “intellectual charlatan,”[8] and accused of merely sympathizing with Trump’s Slovenian wife, Melania.[9] Fiery denunciations arrived swiftly from both ends of the political spectrum: Left Voice demanded that the Left repudiate Žižek,[10] whereas the right-wing online news outlet Breitbart celebrated his endorsement.[11]

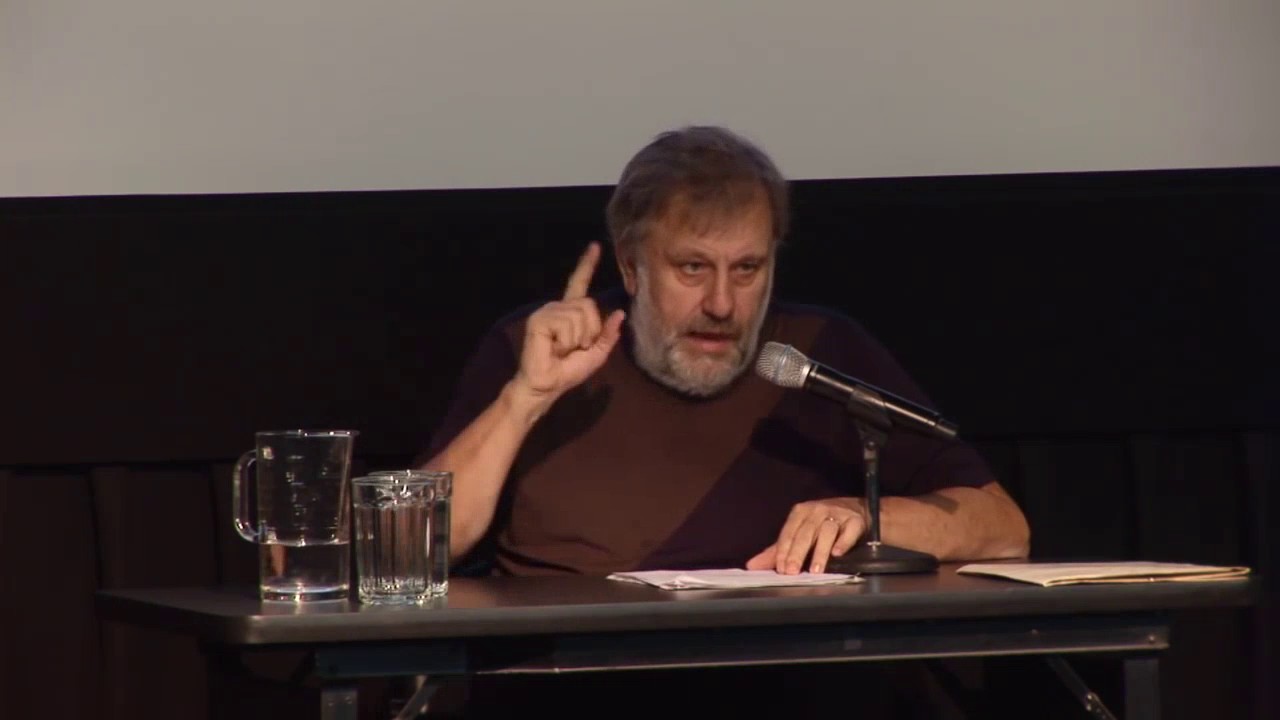

Fast-forward a week. Donald Trump has been elected president of the United States and is in the course of composing his promised right-wing cabinet. Žižek—a visiting scholar in New York—has been invited to speak at New York University the day after the election. A long queue extends out of the Cantor Center, where Žižek is to give his talk: “Racial Enjoyments: What the Liberal Left Doesn’t Want to Hear,”[12]. Students, young first-time voters, and assorted leftists—confused, shocked, speechless—want answers from Professor Žižek. What now? When he emerges on stage, Žižek appears calm and more restrained than usual. While he is known for his provocative performances, the outrage on the Left at his “endorsement” seems to restrain him. Or, perhaps, he has just had enough negative publicity for one week. Yet he sticks to his core argument: Both Trump and Bernie Sanders were political outsiders who captured the anti-establishment mood among the population that Hillary Clinton’s centrism failed to acknowledge. Her victory would have represented an attempted continuation of the status quo in the guise of pragmatic austerity served with a pinch of political correctness. Conversely, Trump, in his politically incorrect manner, spoke to the underrepresented “white working class” and reminded his voters of the half-forgotten concept of class struggle—albeit in a populist and distorted iteration—which had lain dormant in neoliberal politics.

Žižek’s optimistic proposition is cryptic, laconic, and counterintuitive. To reach a more thorough understanding, we need to compare it with other analyses of American politics today. I am particularly interested in three questions: What are the key components of Žižek’s controversial thesis that an apparently regressive figure may eventually, and however indirectly, yield political advances? How and why does Trump appeal to his supporters? What are the presumptions that lead many to reject Žižek’s argument outright?

Žižek’s argument is made up of two dialectically interlinked points: First, leftist and liberal panic over Trump’s supposed fascist tendencies is based on a highly ahistorical reading of fascism. Second, Trump’s election and defeat of the neoliberal Republicans are a direct response to the Democrats’ failure to adapt to the crisis signaled by Sanders. The incumbent president’s rhetoric mobilized these anti-establishment sentiments, setting a precedent for the inert Left’s reactivation.

The first line of reasoning is easily fleshed out. Whereas in common usage the term “fascist” has become a synonym for racist, nationalist, authoritarian, or simply threatening to the present order, the accusation of Trump as a fascist, which appears on myriad protest posters and newspaper articles, is historically inaccurate. In a Jacobin article from December 2015, journalist Daniel Lazare noted that Trump is not a fascist in the classic sense. "[H]e presents himself as an individual—Donald Trump, Inc.—who will single-handedly knock heads and make the system work. The more appropriate term, therefore, is Bonapartist—a tough leader who positions himself above the fray and simultaneously attacks enemies from the Left and the Right."[13]

While rejecting the liberal politics of the Democrats, Trump also shook up the Republican Party’s mechanisms by breaking with their traditional conservatism. Ideologically unaffiliated with either party, he may appear as a populist savior, putatively representing ideas of law, order, and the common good. At the same time, he displays the charisma of an authoritarian leader, appeals to the economically disadvantaged, and relies on nepotism due to his political inexperience—a mode that resembles Louis Bonaparte’s rule in the nineteenth century.[14]

In a Brooklyn Rail article from May 2017, sociologist Michael Mann highlights the distinctions between Trump’s following and actual twentieth-century fascist movements in Germany or Italy. The parallels, such as Trump’s militarism, anti-immigrant policies, and demagogic oratory, fade in the light of historical comparison. Even though there may be large-scale discontent among the American public today, a direct parallel to Weimar Germany or 1920s Italy cannot be drawn. We are not living through the Great Depression, America has not just suffered massive losses from a World War on her own soil, and the country, which functions as a liberal republic, has a legal system and infrastructure that cannot easily be disrupted by a single megalomaniac political figure, nor by his cliquish following.[15] Counter to the liberal perception of Trump as an autocrat, to Žižek, he is more accurately described as a middle-of-the-roader: “Trump is a paradox: he is really a centrist liberal, and maybe even in his economic policies closer to the Democrats, and he desperately tries to mask this. So, the function of all of these dirty jokes and stupidities is to cover up that he is really a pretty ordinary, centrist politician.”[16] While Clinton’s moderation turned into an impediment that failed to acknowledge the vexation of the people, for Trump, who, as a Republican candidate, was expected to run on a more conservative platform, it turned into an asset. Due to his call for ordinary people’s needs, such as creating jobs, raising the minimum wage, and lowering the cost of healthcare paired with a demeanor highly untypical for a conservative politician, he came across as a more unique choice for middle-class voters in comparison to his flagrantly anti-labor fellow Republican contenders.[17] This is probably also how he won electors in the so-called Rustbelt region, which is traditionally Democratic and voted for Barack Obama in the last two elections. Clinton was so sure to succeed in this part of the country that she hardly even campaigned there.[18]

Žižek’s second line of reasoning requires a closer examination of Trump’s support base. According to Žižek, Trump’s biggest asset is precisely his vulgar populism: It not only angered many, but also fundamentally challenged key constituencies within the GOP. Clinton, on the other hand, ran on a wide-ranging consensus that included an improbable agglomerate of diverse political strands, as she attempted to smother the discord manifested and exacerbated by Sanders:

Everybody is there, from Wall Street bankers to Bernie Sanders supporters and veterans of the Occupy movement, from big business to trade unions, from army veterans to LGBT+ activists, from the ecologists horrified by Trump’s denial of global warming and the feminists delighted by the prospect of the first woman president to the “decent” Republican establishment figures terrified by Trump’s inconsistencies and irresponsible “demagogic” proposals.[19]

Both Trump and Sanders emerged from the same widespread frustration with a mainstream politics that could produce such an ill-assorted cluster of constituencies beneath the Democratic Party’s wing. While Trump tackled it through “rightist populism,” Sanders utilized a “leftist call for justice,” and would have represented the only option to diminish Trump’s claim to being an outsider. A crisis thus arose at the political center, which seemed to contain both the establishment and its opposition. Trump poses as a right-winger to appease his base, but seems to be governing like a moderate opportunist; Sanders promoted “socialism” but his welfare reforms appear Social-Democratic at best; and Clinton, in her attempts to appeal to everyone, promised a weak continuation of Obama’s commitment to the status quo, even as the ground was shifting under voters’ feet. We are witnessing a theater of political standpoints that masks how everybody orbits around the center.

By rigging the primaries to rid themselves of Sanders,[20] the Democratic Party ensured that they could continue their practice of adopting cultural struggles—against sexism, racism, etc.—to co-opt dissent. The fundamental strategies of neoliberalism could thus be retained, even in the face of neoliberalism’s crisis. This turn to concerns of social justice overshadows the fact that the Democratic Party has long abandoned the pretense of being “the party of the people.” As George Packer articulates at length in a New Yorker article from October 2016, during Hillary Clinton’s political career, the Democratic Party has turned its attention to a diverse, educated professional class and has lost its working-class base.[21] The presidency of Clinton’s husband Bill marked a major phase in this historic shift during which the ostensible identities of the two parties—Republicans for business, Democrats for social welfare—began to disintegrate.

Stemming from a rural, working-class town, Bill Clinton’s political career began during the 1972 presidential candidacy of Democrat George McGovern. Campaigning in the final years of the Vietnam War, McGovern ran on a strong anti-war platform and galvanized support from young voters, minorities, and activists. While his left-leaning approach spoke directly to social liberals, it alienated the worker and fed directly into an ongoing shift in working class politics. This transformation arose with the crisis of the New Deal era and fully flowered in 1980, when the long-shot Republican presidential candidate Ronald Reagan won a substantial number of formerly Democratic blue-collar voters.[22] The 1990s saw the political success of recent Yale Law School graduates Bill and Hillary Clinton, raised in working-class and middle-class families respectively. They are self-fashioned, idealist “policy wonks” who harbor “business-friendly ideas for economic growth,” oppose traditional workers’ institutions, and assume that every American can follow their lead. By the time Hillary Clinton ran for president in 2016, this promise was plainly unfulfilled. Instead, among those in the country’s rural and poor regions, those unable to enter the professional class, a new identity had formed: the white working class. Overlooked and ostracized by the Democrats’ professionalism, elitism, and moralistic emphasis on ethnic diversity—a situation that continued throughout Obama’s presidency—the white working class looked to alternative political avenues, just like in Reagan’s times.[23]

This is the base on which Donald Trump ran. Skepticism towards identity politics, in which a person’s skin color or gender defines their rights as well as capacities to speak and act, gave a crude figure like Trump an open field. With his boorishness and disregard for political correctness, he appeared like a truth-teller to overlooked sections of Americans and those yearning for change. While the liberal media were spending their time ridiculing working class people for their racial bigotry, gun affinity, and religiosity, a repurposed GOP stepped in. It is, therefore, no coincidence that Trump, a former Democrat, ran as a Republican. As the Democrats morphed into a party of the professional establishment, it became evident that they had never truly been working people’s ally, despite their rhetoric. Consequently, white working class voters turned to the Republican Party, who under its new leadership increasingly appeared as an insurgent faction, rebelling “against changes in color and culture . . . against globalization.”[24] The long neglected “silent majority” responded with marked enthusiasm and sought the candidate that promised them an America in which working people could afford a stable middle-class existence for their families. Trump’s slogan “Make America Great Again”—albeit simplistic at first glance—feeds exactly into these hopes: the adverb “again” indicates the desire to return to better times; the verb “make” bears a strong call for action. His presidential campaign was infused with an appeal for an American reparation that neither Obama’s 2008 slogan “Yes We Can” nor Clinton’s stale response to Trump, “We are great because we are good” could capture. Trump’s promises to bring manufacturing jobs back to the United States and tighten immigration policies endowed this new populist movement with a nationalist bent. As neoliberalism has turned into the status quo and an internationally grounded Left is either nonexistent or fails to build a viable political alternative, the populist Right becomes the voice for people's discontents. Meanwhile, in their complacency, the Democrats continue to accuse working folks of causing their own problems, rather than addressing those problems as products of a failing politics. Unsurprisingly, they refused to see the catastrophe of Trump coming.[25]

Furthermore, the Democrats and their supporters mocked Trump himself, whom their media outlets treated scathingly, as illegitimate from the get-go. But the establishment’s recoil from Trump’s anti-elitist propaganda—bashing his “populism,” political inexperience, and demeanor—proved to be a counterproductive strategy. The elite media’s response only confirmed the efficacy of Trump’s approach and strengthened his message. The more the mainstream media ridiculed him, the more likable he became to ordinary citizens, who already felt dismissed by liberal America. They projected the insults onto themselves and proudly adopted them as their own attributes.[26]

The exit polls confirm the electoral discrepancy between college-educated, mainly liberal Americans and citizens without college degrees. Pew Research reveals the widest gap between college graduates and non-college graduates since 1980: The former mostly supported Clinton whereas the latter predominantly backed Trump. Conversely, race and gender issues played lesser roles than media pundits expected.[27] As the election results suggest, most of Trump’s voters are simply Republicans, who supported their party’s candidate. But then there are the Sanders-Trump crossover voters. 20% of usually loyal Democrats asserted in January 2016 that Trump was their second choice after Sanders for the plain reason that either of these candidates addressed their problems more than a mainstream politician.[28] A Gallup poll from September 2016 reveals that Trump voters are not necessarily the poorest Americans, rather “they tend to be less educated, in poorer health, and less confident in their children’s prospects… They’re more deficient in social capital than in economic capital.”[29] In Marxist terms, they could be seen as prospective participants in a worker’s vanguard, the proletarian layer of society that harbors revolutionary potential and could be organized into a U.S. socialist party. They are explicitly not the most downtrodden that Karl Marx called the counter-revolutionary “Lumpenproletariat,” and Leon Trotsky considered more prone to fascist ideologies.[30] Or as Žižek notes, “this core is dismissed by liberals as the ‘white trash’—but are they not precisely those that should be won over to the radical leftist cause?”[31] The sad truth is, however, that in a politico-historical climate that disallows the development of class consciousness, these people’s dissent merely brought about a new identity, the white working class. They separate themselves from people of color of the same economic class, who could be their brothers and sisters in arms, and hope the right political candidate will finally hear their plea instead of organizing independently. When any change, even if insecure, unknown, and frightening, becomes preferable to no change and a leftist alternative remains absent, a showman like Trump is elected president. Rather than the cause, he is the symptom of the impotence of American politics, an expression of a crisis.

Yet while some blue-collar voters may have been attracted to Trump’s rhetoric, a vast majority feels profoundly disillusioned about all their political choices. George Packer describes how he encountered working people’s desperation and alienation during a visit to a rural town south of Tampa at the height of the 2008 economic recession. Having lost what little they had and with mounds of debt they could never repay in their lifetimes, they experienced the American government as corrupt and unapproachable. When Packer asked these same people eight years later whom they supported in the 2016 election, one man, named Mark Frisbie retorted, “Do they have that line for ‘None of the above’?” Neither the Democratic Clinton nor the Republican Trump were trustworthy candidates for him.[32] Both parties seemed to represent the interests of the powerful, the rich and beautiful, battling over the support of corporations and failing to account for the common man.

For Žižek, a response such as Frisbie’s, is the most adequate in the given political climate. Rather than supporting Trump, Žižek recommends voter abstention. As long as implication with the establishment continues through participating in elections, our opinions can still be influenced, and the system we are trying to oppose may even benefit from it. In this context, eschewing the choice between right-wing options is a valid political intervention. This abstention, however, needs to be a conscious act of protest, rather than a sign of helplessness and renunciation. It must be embedded, in other words, in political organizing and movement building on the Left.[33] At the same time, Žižek still favors the presidency of Trump, whom he calls “scum,” for the simple reason that it harbors a slight possibility for change and may offer a path, however indirect, to the forging of an “emancipatory project.” Trump performs the lousy state of American politics, concretizes its faultiness, and appears like its lone perpetrator. Revealing what we have been unable to acknowledge in this way is the actual source of horror as well as the true opportunity of the Trump regime.

Donald Trump greets a Miami rally on August 25, 2017 as the theme song from "Les Miserables" plays and the video wall displays a reworked image of Eugène Delacroix's 1830 "Liberty Leading the People."

This potential for actual socio-political transformation triggers liberal outrage over Trump much more than his rightist political tendencies. For under capitalism, we have lost the ability to think in dimensions that would allow for genuine reconfiguration. Therefore, real shifts are ungraspable, too terrifying to contemplate. Within this unbalanced system, any activity, any protest, any boycott turns into what Žižek, following Theodor Adorno, calls “pseudo-activity,” superficial dissent that fails to yield actual political change. We must avoid this inactivity disguised as “doing something” at all costs and practice abstention as a dialectical countermeasure to fake praxis. The biggest trap, however, would have been to deem Clinton the “lesser evil” and cast one’s vote for her out of fright. Žižek warns us that in our hysteria over Trump, we idealize the Democrats, who are in reality just as corrupt and not further Left on the political spectrum, thereby strengthening the status quo and continuing to disempower workers. So, if we have to vote, we should vote for Trump.[34]

Žižek has been rather quiet in the tumultuous post-election period. One article on this topic was published in The Philosophical Salon in January 2017, which feels like a long time ago. In an article addressing this, Žižek laments the Democratic response to the election outcome that expresses itself either through panic or complacency. He draws a parallel to the Polish PiS (the ruling rightist populist party) that dedicates itself to anti-austerity measures and improved living standards for the poor in a nationalistic fashion, whereas the so-called Left would have implemented austerity politics under the guise of cosmopolitanism. What if, Žižek asks, Trump would take a similar turn?[35] After all, his final campaign video, as well as victory speech, bear Bernie-esque populist features if one disregards the nationalistic, anti-illegal immigrant elements, as Tad Tietze points out in a Left Flank article from November 2016.[36] Furthermore, while there were wide discrepancies between his campaign policies and those of Sanders, some parallels can be found with regards to rebuilding infrastructure, implementation of fair trade, and retention of Social Security.[37] Whether Trump will have the opportunity to carry out any of these plans—assuming they are genuine—is still to be seen. Considering the amount of discontent with his crude travel ban, apparent support of a regressive Republican health care reform, and abrupt firing of FBI Director James Comey, it becomes increasingly unlikely. But it is also still too early to gauge any long-term effects the election of a figure like Trump—an acutely personified expression of neoliberalism’s crisis—will have on American and global politics.

For the present, it might be advisable to follow Žižek’s recommendation in The Philosophical Salon: self-reflection. He points out the distinction between fear, which focuses on an external object’s threat to one’s identity, and anxiety, which functions through introspection and may thus allow for self-examination. In today’s political climate, both rightist xenophobia and leftist dread of change are products of fear. Instead, Žižek asks us to scrutinize the identities that we strive to protect. Since the Democrats are not a liberal, pro-labor alliance, and the Republicans seem destined to fragment under the pressure of Trump’s presidency, then the parliamentary system is in crisis, which may create the opportunity to forge an alternative, leftist political party. If as Gore Vidal used to say, America is a one-party state with two right-wings, why not unify the right wings and create a genuine two-party system? In this context, it is worth recalling that Bill Clinton signed the 1994 Crime Bill, which contributed to mass incarcerations of African Americans,[38] that under Obamacare 33 million people remained uninsured and 21% of those with insurance were categorized as underinsured,[39] and that the seven Muslim countries that Trump temporarily banned from entering the U.S. were selected under Obama.[40] It is also worth retracing what Trump pointed out in his campaign: that the party political system is “rigged,”[41] that labor participation rates are depressingly low, and that the political class as a whole is hopelessly incompetent and out of touch. The politics of multiculturalism comes to be exposed as the project of a cosmopolitan elite and the concern of human resources departments. As the living conditions of ordinary people fail to improve or even decrease, we need to question our categorizations and potentially revive a class-based politics that appeals to the great majority of America. After all, during Obama’s eight years of presidency, the situation of African Americans failed to improve, and the highest number of deportations was recorded.[42]

If the canon of political correctness amounts to nothing but language policing and the successes of the Left are celebrated as “changing the conversation,” such as Occupy Wall Street’s 99% or Sanders’ destigmatization of the term “socialism” in public discourse, we are setting the bar too low. Let us take a look, for instance, at the widely acclaimed Women’s March on Washington that took place on January 21st, a day after Trump’s inauguration. The main topics of discussion were race and gender in relationship to white male privilege that the 45th president of the United States appears to epitomize, whereas demands that might appeal to working citizens of all backgrounds, such as healthcare, childcare, and parental leave—demands that would have given the march political significance—were scarce.[43] What does this coalition of politically unaffiliated groups, which tails after the Democrats, perform if not pseudo-activity?

Only if we introspect instead of holing up in our fear of change or of an egomaniac president, instead of hoping our misfortunes will be remedied through the right Democratic candidate, then social change may yet be possible. Orienting ourselves this way is what Žižek—somewhat idealistically—proposes. If we want to be critical of Trump, we need to understand how he came to power and to study the people that supported him, so we can oppose him and the social structures that allowed his rise to power. We need to acknowledge and use people’s anti-establishment sentiments instead of dismissing them as the racist ravings of “white trash,” while challenging the illusion that the Democrats represent women and minorities. Most importantly, however, we need to reach even beyond introspection and practice radical self-criticism of our history, the history of the Left, so that we may recognize our errors and learn how to overcome them in an organized manner. Žižek’s hopeful pessimism presupposes that the Left—inert, ossified, and obfuscated by identity politics as it is—might reawaken to address the deepest resentments, and thus the profoundest potential, of working people. But whether this can be accomplished in a society that continues to blur the lines on the political spectrum and has made the development of class consciousness close to impossible, remains an unwritten book for the time being. |P

[1] Ippolit Belinski, “Slavoj Žižek would vote for Trump,” YouTube, 1:52 mins, November 3, 2016: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b4vHSiotAFA

[2] Conor Lynch, “Donald Trump is an actual fascist: What his surging popularity says about the GOP base,” Salon, July 25, 2015: http://www.salon.com/2015/07/25/donald_trump_is_an_actual_fascist_what_his_surging_popularity_says_about_the_gop_base

[3] M. Dov Kent, “Donald Trump's bigotry against Muslims has safety implications we can't ignore,” The Guardian, November 20, 2015: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/nov/20/donald-trump-bigotry-has-real-safety-implications

[4] Nadia Khomami, “Donald's misogyny problem: How Trump has repeatedly targeted women,” The Guardian, October 8, 2016: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/oct/08/trumps-misogyny-problem-how-donald-has-repeatedly-targeted-women

[5] Socialist Worker-Year of the Renegades, Socialist Worker, January 21, 2016: http://socialistworker.org/2016/01/21/year-of-the-renegades

[6] Alexandra Rosenmann, “Noam Chomsky Drops Truth Bomb on Trump’s Election, ” Alternet, November 25, 2016: http://www.alternet.org/election-2016/post-election-noam-chomsky-drops-trump-bomb-trump-voters-wanting-shake-systempost

[7] Hamid Dabashi, “Why Chomsky and Žižek are Wrong on the US Elections,” Al Jazeera, November 30, 2016: http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2016/11/chomsky-zizek-wrong-elections-161129090634539.html

[8] Andre Damon, “The idiot speaks: Slavoj Žižek endorses Donald Trump,” World Socialist Web Site, November 9, 2016: https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2016/11/09/zize-n09.html

[9] Alex Shephard, (2016) Minutes, New Republic: https://newrepublic.com/minutes/134505/slavoj-zizeks-take-donald-trump-zizek-y

[10] Ian Steinman, “From Farce to Tragedy: Žižek endorses Trump,” Left Voice, November 4, 2016: http://www.Leftvoice.org/From-Farce-to-Tragedy-Žižek-Endorses-Trump

[11] Lucas Nolan, “Left-Wing Philosopher Slavoj Žižek: ‘I would vote for Trump’,” Breitbart, November 4, 2016: http://www.breitbart.com/2016-presidential-race/2016/11/04/left-wing-philosopher-slavoj-zizek-i-would-vote-for-trump/

[12] Deutsches Haus, “Slavoj Žižek—Racial Enjoyments: What the Liberal Left Doesn’t Want to Hear,” YouTube, 1:50:10 mins, January 5, 2017: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7lrU_ZX15C8

[13] Daniel Lazare, “Is Trump a Fascist?,” Jacobin, December 15, 2015: https://www.jacobinmag.com/2015/12/donald-trump-fascism-islamophobia-nativism

[14] Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, trans. Daniel de Leon (Digireads 2012).

[15] Michael Mann, “Is Donald Trump a Fascist?” Brooklyn Rail, (May 2016): 105.

[16] Marcus Browne, “Slavoj Žižek: 'Trump is really a centrist liberal’,” The Guardian, April 28, 2016: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/apr/28/slavoj-zizek-donald-trump-is-really-a-centrist-liberal

[17] Nikos Malliaris, “Freedom from progress: Donald Trump, Christopher Lasch, and a Left in fear of America,” The Platypus Review, March, 2017: https://platypus1917.org/2017/03/06/freedom-progress-donald-trump-christopher-lasch-left-fear-america/

[18] Tad Tietze, “A few thoughts on the Trump victory and the Left,” Left Flank, November 10, 2016: https://left-flank.org/2016/11/10/a-few-thoughts-on-the-trump-victory-and-the-left

[19] Slavoj Žižek, “Clinton, Trump and the Triumph of Global Capitalism,” In These Times, August 24, 2016: http://inthesetimes.com/article/19410/clinton-trump-and-the-triumph-of-ideology

[20] Glenn Greenwald, “Tom Perez Apologizes for Telling the Truth, Showing Why Democrats’ Flaws Urgently Need Attention,” The Intercept, February 9, 2017: https://theintercept.com/2017/02/09/tom-perez-apologizes-for-telling-the-truth-showing-why-democrats-flaws-urgently-need-attention/

[21] George Packer, “Hillary Clinton and the Populist Revolt,” The New Yorker, October 31, 2016: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/10/31/hillary-clinton-and-the-populist-revolt

[22] See Jefferson Cowie, Stayin’ Alive (New York: The New Press, 2010), 6-18.

[23] George Packer, “Hillary Clinton and the Populist Revolt,” The New Yorker, October 31, 2016: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/10/31/hillary-clinton-and-the-populist-revolt

[24] Ibid.

[25] Thomas Frank, “The Democrats' Davos ideology won't win back the midwest,” The Guardian, April 27, 2017:

[26] Slavoj Žižek, “Donald Trump’s Topsy-Turvy World,” The Philosophical Salon, January 16, 2017: http://thephilosophicalsalon.com/donald-trumps-topsy-turvy-world

[27] Alec Tyson and Shiva Maniam, “Behind Trump’s victory: Divisions by race, gender, education,” Pew Research Center, November 9, 2016: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/11/09/behind-trumps-victory-divisions-by-race-gender-education

[28] Elizabeth Bruening, “What Explains the Trump-Sanders Crossover Vote?” The New Republic, January 12, 2016: https://newrepublic.com/article/127442/explains-trump-sanders-crossover-vote

[29] George Packer, “Hillary Clinton and the Populist Revolt,” The New Yorker, October 31, 2016: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/10/31/hillary-clinton-and-the-populist-revolt

[30] Leon Trotsky, “How Mussolini Triumphed,” What Next? Vital Question for the German Proletariat, 1932: https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/works/1944/1944-fas.htm - p2

[31] Slavoj Žižek, “Up for Debate: The Lesser Evil,” In These Times, November 6, 2016: http://inthesetimes.com/features/zizek_clinton_trump_lesser_evil.html

[32] George Packer, “Hillary Clinton and the Populist Revolt,” The New Yorker, October 31, 2016: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/10/31/hillary-clinton-and-the-populist-revolt

[33] Slavoj Žižek, “Why bother to vote?” The Guardian, September 29, 2007: https://www.theguardian.com/theobserver/2007/sep/30/featuresreview.review11

[34] Slavoj Žižek, “Up for Debate: The Lesser Evil,” In These Times, November 6, 2016: http://inthesetimes.com/features/zizek_clinton_trump_lesser_evil.html

[35] Slavoj Žižek, “Donald Trump’s Topsy-Turvy World,” The Philosophical Salon, January 16, 2017: http://thephilosophicalsalon.com/donald-trumps-topsy-turvy-world/

[36] Tad Tietze, “A few thoughts on the Trump victory and the Left,” Left Flank, November 10, 2016: https://left-flank.org/2016/11/10/a-few-thoughts-on-the-trump-victory-and-the-left

[37] Tamara Keith, “5 Ways Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump Are More Alike Than You Think,” NPR Politics, February 8, 2016: http://www.npr.org/2016/02/08/465974199/what-do-sanders-and-trump-have-in-common-more-than-you-think

[38] Robert Farley, “Bill Clinton and the 1994 Crime Bill,” Fact Check, April 12, 2016: http://www.factcheck.org/2016/04/bill-clinton-and-the-1994-crime-bill

[39] “Background Fact Sheet Beyond the Affordable Care Act: A Physicians’ Proposal for Single-Payer Health Care Reform,” American Journal of Public Health, June 2016:

[40] Tom Kertscher, “Were the 7 nations identified in Donald Trump's travel ban named by Barack Obama as terror hotbeds?” Politifact Wisconsin, February 7, 2017: http://www.politifact.com/wisconsin/statements/2017/feb/07/reince-priebus/were-7-nations-identified-donald-trumps-travel-ban

[41] “Trump: 'Our system is rigged',” Chicago Tribune, October 13, 2016: http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/91719444-132.html

[42] Serena Marshall, “Obama Has Deported More People Than Any Other President,” ABC News, August 29, 2016: http://abcnews.go.com/Politics/obamas-deportation-policy-numbers/story?id=41715661

[43] Farah Stockman, “Women’s March on Washington Opens Contentious Dialogues About Race,” The New York Times, January 9, 2017: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/09/us/womens-march-on-washington-opens-contentious-dialogues-about-race.html