The ironies of Trump’s education policy

Laura Lee Schmidt

Platypus Review #94 | March 2017

On January 23, two days after his inauguration, President Trump issued a draft order for visa reform proposing to regulate the H-1B visa, which among other things, allows CEOs in Silicon Valley to hire high-skilled foreign-national engineers who work for less in exchange for visas. This reform could increase wages down the line; it could bring more American workers into the ambit of innovation, and increase the ranks of the skilled; it could bring tech hiring practices into the public awareness. Its speculative intent definitely miffed tech CEOs, though.[i] Trump’s lack of motive to articulate what he is doing has not swayed people from their certainty that it will surely end in disaster—and judging from the urgency of some of these claims, probably personal disaster. Not so for the workers who voted for him, to whom his policies have remained faithful.

Trump has not acted on his draft order yet, mostly because of the outcry against his executive order that halted immigration and asylum from seven nation-states (which also rankled tech). The order was geared to national security, but Trump has associated workers with immigration from the first. The protests papered over the question of workers and focused on moral judgment. They were pacified by decisions by regional courts, which upheld the order’s suspension by appealing to education. Minnesota and Washington’s claims of injury (which is necessary to rule against an executive order) were that the order would hurt their public research universities by restricting the movement of faculty from those countries. Alongside the tech CEOs, the research universities have proffered proprietary definitions of immigration as “the free circulation of people,” in other words, the signature of a larger game for the returns on the purchase of labor—for surplus value and the social rules it engenders. Many who do not support Trump’s order have questioned the validity of the ruling, but what’s done is done: it revealed that education has a special knack for concealing its own role in the game of capitalism.[ii]

The administration has chosen not to argue the point, however weak the ruling: Trump will instead issue a new order. Indeed, Trump has been rather mum on education—not like Ronald Reagan, who wanted to dissolve the Department of Education. If his other words and acts loudly proclaim a crisis of capitalism hitting American workers and the political establishment’s silencing of them, he has publicly clarified less about the potential free education plays in that crisis, and more or less repeats Republican positions on schooling. His Secretary of Education, Betsy DeVos, whom he nominated at the close of November, also repeats, in a soft nasal tone, all the usual Republican watchwords. She decries public monopolies, favoring instead charter schools and states’ authority, and she attributes public schools’ failure to lacking market choices, etc. As education loudly comes in to “defend the status quo,”[iii] it might yet open up a possibility that has not been available for a while: to critically think about education by discerning some of its politics.

After the Financial Crisis of 2008 drove many millennials to seek higher education, it has been awash with emotion. This inflated the ranks of academia, increased contract-hiring, and reignited the “culture wars.” The more these labor conditions were publicized, the more productive schooling became for coping. Rather than teaching how to deal with the world, education has muddled thinking about it. Kanye West captured one facet of the psychological typology in 2007: “Scared to face the world, complacent career student.”[iv] The career student’s debt briefly stoked his sympathy for Occupy Wall Street in 2011, which lent an “anti-capitalist” mien to politics that Iraq War protest could not provide. Since 2008, it might have seemed as though the tides of Marxism were coming in—in with Obama—but it was just neoliberalism bridging the growing space between a whole generation and its entrance into life itself. The Democratic Party used the first decades of the new millennium to curry the emotional neediness that contemplating this fate seems to inspire, and with it, made education into its ideological binding agent for depoliticized people.

That DeVos—daughter of a billionaire auto-parts-manufacturing tycoon, sister of the founder of the private security firm Blackwater, wife of Amway scion and owner of the Orlando Magic—whetted great resistance amongst liberal, left Democrats attests to the moral authority of education and its ideological power. Of course, many Democrats under Obama worked with DeVos; many supported charter schools; and Obama’s second Secretary, Arne Duncan, fell out of favor because he lost the unions with his neoliberal agenda. Lily Eskelsen Garcia, the current president of the largest union today, the National Education Association, has said, “Betsy DeVos is an actual danger to students—especially our most vulnerable students. She has made a career trying to destroy neighborhood public schools, the very cornerstone of what's made our nation so strong.”[v] It’s incredible how strong the association with Democrats and education now is when you consider how before the twentieth century, the Democrats as a political party were against education. But because education has helped make critical social issues incomprehensible through neoliberalism, the history of it too has been divested of political import as though education had little to do with thinking itself.

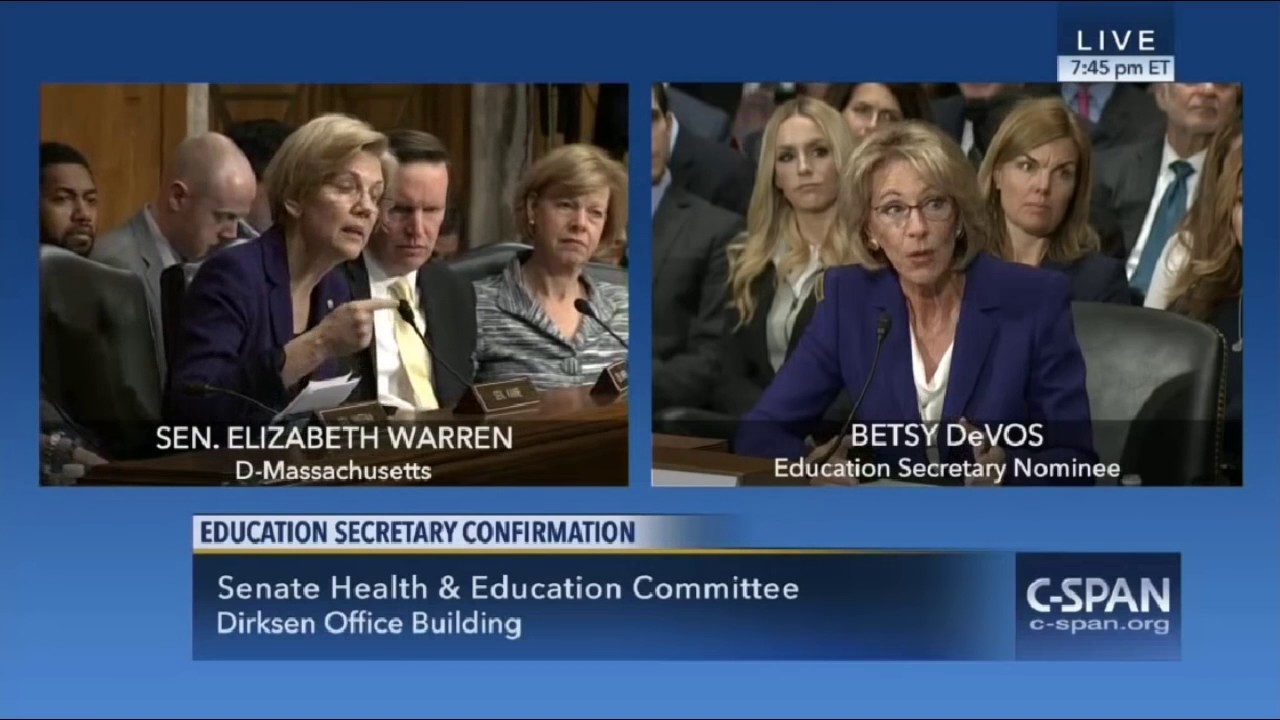

Betsy DeVos faces off against Democrats in Hearing for Secretary of Education. DeVos argued for less government control in education.

Since schools cropped up in the American colonies, and especially after the American Revolution, education has been rooted in a freeholder’s prerogative to send his children to school—it is a bourgeois right. During antebellum industrialization, cities around the expanding country developed sizable systems for “universal free education,” but the uneven absorption of people into the labor market, failed liberal revolutions in Europe, and slavery in America seemed to cast doubt on that claim. All three of these things factored into the Civil War, and a proper national system of public education in America sprang from the political-legal aftermath of Reconstruction. Radical Republicans pushed for the creation of a Bureau of Education (with a non-cabinet Secretary of Education) to collect information on education across the country while contracting out the construction of schools for emancipated youth in the South. Education certainly figured into cultural opportunities opened by emancipation, but that is because emancipation extended a bourgeois right of free labor to the whole country; Radical Reconstruction subordinated the resulting state to the political authority of Northern victory in the Civil War, and Radical Republicans used education to bolster this political domination. Not quite as effective as federal troops deployed to enforce Reconstruction, but a provocation all the same.[vi]

With these changes came great political resistance. After 1876, when the two parties current to this day brokered Republican Rutherford B. Hayes’s presidency in exchange for granting Democrats’ wish for amnesty for ex-Confederates and an end to federal Reconstruction, the inflating scholastic bureaucracy and abundant labor unrest that followed financial crisis marked a shift in the politics of capitalism. In 1880, after Republicans elected their presidential candidate James Garfield, civil rights lawyer Albion Tourgée published an essay called, “Aaron’s Rod in Politics,” in which he commended the party for including education in its platform. Education had become necessary in light of the “new point of departure” of the Civil War. Democrats sneakily co-opted the votes of freedmen, who tended to vote Republican but whose lingering high rates of illiteracy facilitated electoral swindle. Democrats formed alliances with embittered ex-slave-owners, and a coalition that literally spoke of itself as “the South” and spoke too on “the South’s” behalf, hid all this reality from voters.[vii]

Tourgée was not merely claiming freedmen needed to be brought into a public sphere of opinion—that was a longstanding demand for free men black and white. There was something more urgent about the political tenor of education after Reconstruction. Political comprehension had to extend beyond the elections to grasp the stakes of the Civil War, which he likened to revolution and whose thwarting he anticipated. He named his essay after the staffs Moses and his brother Aaron wielded that performed miracles, and commanded authority over the Israelites; education represented “miraculous authority” in politics. It allowed people to learn to desire and achieve higher historical goals. The Democratic Party encouraged its suppression, and the South used that racket to gain domination over the political scene that emerged from Reconstruction, an act which Tourgée at least, seeing the power of education, called counterrevolution.

In the 1880s and ’90s political parties vied for the votes of a group of Southerners whose votes were rescinded by Jim Crow by the end of the century. But during those two decades, the Populist Party promoted bourgeois rights for both black and white workers as they attempted to penetrate the South, and the party seemed capable of facilitating political education. But the South was “the South,” and alongside Northern juridical resistance to Populism, racial superstition was absorbed into law. Racism provided poor whites with high priests, the ex-slaveowners and their hangers-on who made it feasible for the Democratic Party to Latinize and present before Congress. Jim Crow, the ghastly product of the failure of Reconstruction, stripped away many basic rights, and it begot lasting racist segregation of public schools which used education to divide and conquer workers.

Writing books used to teach penmanship during Reconstruction.

At the same time, in the same context, a set of reforms to public schools, Progressive Education, integrated psychological theories formulated by experts and experimenters from the American research universities, which had gained clout with the state bureaucracy by the turn of the century. Concepts like “content of children’s minds” were useful for evaluating the performance of schools, and were adapted to scientific management strategies for maximizing “efficiency” and “output,” although it remained unclear exactly what the product was.[viii] This collapsed pedagogy, or what ought to be taught and how, into management of schools. These scientific innovations helped to neatly divide the estimation of the value of public schooling in two: the social task of spending on the one hand, and the execution of the legal right to schooling on the other. The literal unification of pedagogy and management under the rubric of democracy (and the party that stood for it) separated out spending issues, which by the power of gravitational pull coalesced into an ideological issue.

Milton Friedman came up with the voucher system in 1955. He thought that the state should pay for schools, but not run them. So far, Trump has left unpolished the neoliberal patina of school choice and charter schools. He has also just moved to take out the school restroom transgender protection guideline that the Obama Administration included under the Title IX Act (1972), which forbids schools that receive any federal aid from prohibiting based on “sex” the use of educational programs and facilities. Setting aside for a moment the ire this has drawn from Democrats and left liberals, Trump has argued that the guideline does not fall under federal law, which also includes federal money for private school programs. It might appear to be a partisan move, but it has concerned even Betsy DeVos, who expressed private chagrin with respect to Trump’s restroom reversals.[ix] She might not have the legal expertise to grasp the scope of the reversal, but her interest in a major moral appeal made by the Democratic Party shows how greatly the Democratic Party’s inflections defend the neoliberal status quo. It also points to the fact that, on education, the space between Republican and Democrat is incredibly blurry.[x] Trump stands out against the background.

What both parties tend to say about education betokens a fear of its powers. The most provocative thing about DeVos might be how bluntly she says that public schools, such as they are, have failed. For her, as for most Republicans, the failure of public schools just means teachers’ unions have failed “the nation’s children,” and it translates to a hysterical defense of parents’ choice over what school their kids attend, as though each and every missed opportunity to choose were the result of organized labor knocking at the door, kidnapping the child. But in the paranoid, bipartisan language of neoliberal public education, where “teacher” does not mean “union thug,” it conjures the martyr of a community. Public schools are tools for equality for the Democrats and left liberals, the closest thing to a social welfare ideal. That makes teachers combatants of generational poverty and holds them responsible for the decline of schools: an impossible feat. But both parties fear what education—mass, public, or universal—really invokes, politically, which is the education of the proletariat.

Luckily for them, there is no active pursuit of this, although there is something uncanny about Trump’s orientation to workers.[xi] In the weeks following his declaration of his candidacy in the summer of 2015, onlookers were already embroiled in nomenclature, until a consensus was reached that here was a populist, like Berlusconi, who sometimes leans fascist, like Mussolini. That is the logic of the absence of a socialist party, our realm, in which the enfranchisement of workers smacks of populism, which always was a threat to the Democratic Party. Populism is not a word Trump uses, but its use against him only sows confusion amongst everyone but him.

The charges of stupidity may have suited the era of George W. Bush (and brought out his artistic vision, years later), but they do not suit Trump. Not taking him seriously—not feeling intellectually tasked by the 63 million voters—is a personal choice which, like homework, is only forced the extent to which one believes the teacher assigns it out of abuse of authority. The incoherence introduced into education throughout the twentieth century has helped obscure what an achievement millions of peoples’ education would actually be. At its best, public education’s failure in America, legible through Reconstruction’s failure, insinuates how the social and cultural desires encapsulated in “education” could only be achieved by revolution.

Trump does not want revolution, of course. He does defend the American Revolution. What remains opaque to him is the Civil War and Reconstruction, in which the politics of workers’ education gifted to America a historical legacy of the proletariat. Early in his bid to run for president, claiming to reduce the number of “anchor babies,” Trump did briefly toy with the idea of taking away birthright citizenship, the very thing that made the slave a citizen of a bourgeois republic, and a great political achievement expressed in the Fourteenth Amendment. Trump could never have undone that, because he cannot change history.

Trump’s own experience and education lie in the purview of “industry”: in turning a profit, managing managers who hire a workforce, working with contractors, and contracting deals. He is a capitalist, and so are the members of his executive cabinet. The deal is an art, not a social science. The knowledge he calls for is speculative; it makes you think, and it is not about facts. He manifests no interest in pedagogy. He is not a Democrat or Republican vying for seats to protect special business interests, and he does not tremble at the ideological proposition of mass education because he does not have the historical interest. The simple point he seems to make is that education has impeded on progress—meaning capitalism.

Trump acts to save capitalism on its own terms, a feat which is of course impossible. In a tragedy, the protagonist does not know the full weight of his words. The spectator, however, must try to learn. He too suffers the enunciations. The spectator’s suffering culminates in a tragedy’s argument, which comes crashing down as a revelation of fate, laying waste to the spectator’s own righteousness, for it too lies in the revelation’s path. For tragedy to be more than cheap revelry in knowledge and certainty, the spectator has to risk learning a lesson from the protagonist, who never claimed to be his teacher.

The drama that has been unfolding for the past several months only really just began with the inauguration of its protagonist, President Trump. What would make it a sad story is if no one were watching. It behooves the spectator’s edification—and surely no one would deny him this goal—to coldly observe Trump’s embrace of the worker’s genius of productivity, that which would “make America great again.” He says this earnestly, but the phrase exudes the irony of a classical tragedy. And with respect to education, he seems to anticipate the irony and sticks to textbook Republican values, but his thinking surely goes beyond that. If education got in the way of progress under neoliberalism, imagine what its fulfillment by a proletariat educated as only the bourgeois dreamed could do. Maybe it could change the rules of the game. |P

[i] Elizabeth Dwoskin and Todd Frankel, “Tech Firms Debate how Strongly to Protest Trump’s Order,” Washington Post, January 30, 2017.

[ii] Jeffrey Toobin, “The Ninth Circuit’s Vulnerable Decision,” The New Yorker, February 11, 2017, available online at <http://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/the-vulnerabilities-in-the-ninth-circuits-executive-order-decision >.

[iii] Trump tweeted after DeVos’ confirmation: “Senate Dems protest to keep the failed status quo. Betsy DeVos is a reformer, and she is going to be a great Education Sec. for our kids!” Donald Trump, Twitter post, February 7, 2017, 5:14 a.m., <twitter.com/potus/status/828955104082526208?lang=en>.

[iv] “Good Morning,” Graduation. Chung King Studios, Sony Studios. September 11, 2007.

[v] Emma Brown, “Teachers Unions Mount Campaign Against Betsy DeVos, Trump’s Education Pick” The Washington Post, January 9, 2017. Available online at <www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/teachers-unions-mount-campaign-against-betsy-devos-trumps-education-pick/2017/01/08/1b60f2d2-d452-11e6-a783-cd3fa950f2fd_story.html>.

[vi] This was encapsulated in the Reconstruction Amendments (the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments), which covered emancipation, citizenship, and limited the states’ powers to curtail these rights.

[vii] Albion Tourgée, “Aaron’s Rod in Politics,” North American Review 132:291 (February 1881), 139-162: 141.

[viii] Around the time that Frederick Winslow Taylor published his theories on time-discipline in factories in 1914, they had been around for decades, such that educational reformer and journalist Joseph Mayer Rice devised Scientific Management in Education, a startlingly literal adaptation of Taylor’s works to schools. The point was to render learning less “mechanistic” by calculating the amounts of time that ought to be spent on a certain lesson. G. Stanley Hall, Adolescence: Its Psychology and Its Relations to Physiology, Anthropology, Sex, Crime, Religion, and Education (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1904); John Dewey, Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education (New York: Macmillan, 1916).

[ix] Richard Perez-Peña, “Though Polite in Public, DeVos Is Said to Get Her Way,” New York Times, February 24, 2017.

[x] The Obama administration’s educational track record especially confused the matter. Obama’s second secretary lost the back of the unions—very grave in Democratic circles—with his standards-based policies. Valerie Strauss, “Democrats reject her, but they paved the way for her nomination” Washington Post, January 21, 2017. Available online at <www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2017/01/21/democrats-reject-her-but-they-helped-pave-the-road-to-education-nominee-devos/?utm_term=.79aaf78f2320>.

[xi]After the election, left progressives tried to piggyback off Trump’s “populism” while washing their hands of his “nationalism,” all in an attempt to win back the Democratic Party for Bernie Sanders. Seth Ackerman, “A Blueprint for a New Party,” Jacobin. November 6, 2016. Available online at: < www.jacobinmag.com/2016/11/bernie-sanders-democratic-labor-party-ackerman/>. They conceive of a labor party as a workers’ party, but use an essentially neoliberal notion of workers: obscured by education, but also ignoring its political importance. This was anticipated last December by Chris Cutrone in “The Sandernistas: The final triumph of the 1980s,” Platypus Review 82 (December 2015), available online at <platypus1917.org/2015/12/17/sandernistas-final-triumph-1980s/>, and in a postscript in the context of Trump and the primaries, “The Sandernistas,” Platypus Review 85 (April 2016), available on line at <platypus1917.org/2016/03/30/the-sandernistas/>.