The most revolutionary weapon: An interview with Nelson Peery

Edward Remus with Greg Gabrellas

Platypus Review #81 | November 2015

Nelson Peery was active in revolutionary politics for 76 years until his death on September 6, 2015. Politicized in the Communist Party, USA (CP) and later its Left Caucus, Peery left the CP in the 1950s on anti-revisionist grounds to form the Provisional Organizing Committee to Reconstitute a Marxist-Leninist Communist Party (POC). Expelled from the POC in the wake of the 1965 Watts rebellion, Peery helped to found the California Communist League and played a leading role in this tendency’s subsequent formations: the Communist League, the Communist Labor Party, and the extant League of Revolutionaries for a New America. Peery’s death prompted members of the Platypus Affiliated Society to recover and transcribe the recordings of two interviews conducted some years earlier. The first interview, conducted by Greg Gabrellas and Edward Remus on September 13, 2011, was broadcast live on the Chicago- based radio station WHPK 88.5 FM. Remus conducted an extended follow-up interview in Peery’s home on March 9, 2012. What follows is a compiled and edited transcript of these conversations.

Edward Remus: Since the founding of the American Communist Party and John Reed’s report to the Second Congress of the Communist International, Marxist thinkers in America have tasked themselves with understanding the implications of race and racism for revolutionary politics. How has your thinking on this question changed over time?

Nelson Peery: The question of race in America has changed along with the changing economy. The modern period of the race question in America started with the destruction of Reconstruction after the Civil War. The role of the individual in history is very important. If Lincoln had lived, they would have perhaps solved the problem to a great extent within four or five years of Reconstruction. They murdered Lincoln because he was willing to give the right to vote to black veterans and literate blacks. When Johnson took over as President it took another hundred years to achieve what Lincoln could have achieved in about five years. But what was the foundation of Reconstruction after Lincoln? It was based on using the results of the Civil War—“waving the bloody shirt,” so to speak—in order to galvanize American opinion to punish the South. And punishing the South meant that Wall Street bought up the South and reduced the Black Belt area of the South to the level of a colony. The consequence was that the South became a hinterland.

At the beginning of the Civil War, the South was twenty per cent richer than the North, and richer in culture too. After the Civil War, the South was progressively reduced to a backwater, whether we’re talking about education, healthcare, or housing. This colonial situation was exacerbated by the color question. The race question was used to hold the entire area down. There’s nothing new about instigating tribes to fight one another, having different peoples of the same nation or of the same geographic area—in this case, the Black Belt—fight one another to the benefit of an invader. The Indians conquered India for the British, the Africans conquered Africa for the British and the French, the Vietnamese conquered Vietnam for the French, etc. In America it was the race question that was pervasive. Chattel slavery had reduced human beings to the level of property, such that trying to integrate freed blacks into American society was very, very difficult. A culture of a hundred years had to be overcome. The situation of the black didn’t allow anything to move: The poorest white people were in the Black Belt too. This made it an area with the greatest possible return on investment, much like Brazil and the Congo. By the end of Reconstruction that area was a secure domain for Wall Street. Three-fifths of the plantations in the Black Belt were owned by Wall Street corporations, especially by United States Steel. They had Southern whites run them but these corporations owned them. However, it was easier to deal with the superficial features of the problem rather than look at its fundamental characteristic—namely, imperialism, the investment of finance capital.

I was a bricklayer when bricklayers in Chicago got twice the rate of the bricklayers in Birmingham, Alabama. It was a given that we didn’t organize the South—“We will let you organize Chicago provided you stay out of Birmingham.” I didn’t consider the entire South to be a developing nation but I did consider the Black Belt one. And most parts of the Black Belt were either very heavily or completely African-American. In the development of the current reaction within the United States, going back to the late 1940s and early 1950s, there was a drive toward glorifying southern culture, eating goober peas, celebrating Robert E. Lee, etc. That reaction is based in the Black Belt. Things have changed now, but I’ve differed from the Communist movement in seeing this as a question of (at least an incipient) national development. We’re talking about the oppression of an area, not simply about the oppression of blacks.

ER: How does your view differ from that of the Communist Party USA (CP) during the 1930s?

NP: Recall the story of the blind men and an elephant. That has been the American people on the African- American question. Is it class? Is it caste? Is it race? Is it nationality? Is it color? We were totally blind; we didn’t know how to describe the question. Neither did the CP. Hitler said of Stalin: “You can’t help but admire him. He took 168 warring nationalities and combined them into one unified state. If I capture him I think I’ll send him to a spa, but I’ll hang Roosevelt and Churchill!” The only example of solving the question of warring nationalities was provided by the Soviet Union so the easiest thing to do was to treat the African-American question as a national question. But this was wrong from the beginning. America isn’t the Soviet Union!

Above everything else, a nation is a community. They say that the community is the black people, the African-American people, but I don’t think so. They live all across the country, they lack a common religion, etc. Nothing held the African-American people together except for segregation. The minute that segregation was lifted they flew into their respective classes. Even the term “African-American” is chauvinistic. Africa is not a nation! Africa is a series of nations, and warring nations at that. Am I supposed to call you European- American? No, you’re Polish-American, and only for one generation—after that you’re American! When am I going to be American? This color question is so deep in the consciousness of Americans, black and white, that they can’t see reality. Remember that there’s no color racism before 1400 or 1500! There was a racial distinction between Slavs and Romans, etc., but no color question. It was only to justify African slavery that the color question was created.

Is there a national question? I’m convinced there is. That national question concerns the community we call the Black Belt. It’s lying dormant right now; it’s going to erupt again later. Political reaction in America has its foundation in the Black Belt. Poor whites and poor blacks have a common history there. There is a community, but it’s not only black. It’s black and white. There’s a difference in saying the question is a national question but not a color question. We tried to prove this in Negro National Colonial Question (1975). You can’t solve an objective process subjectively. Your ideas are not going to make reality; reality has to make your ideas! That’s the difference between Marxism and all the rest. Marxism says: “It’s the interaction!” Yes, your ideas impact reality, but reality creates your ideas.

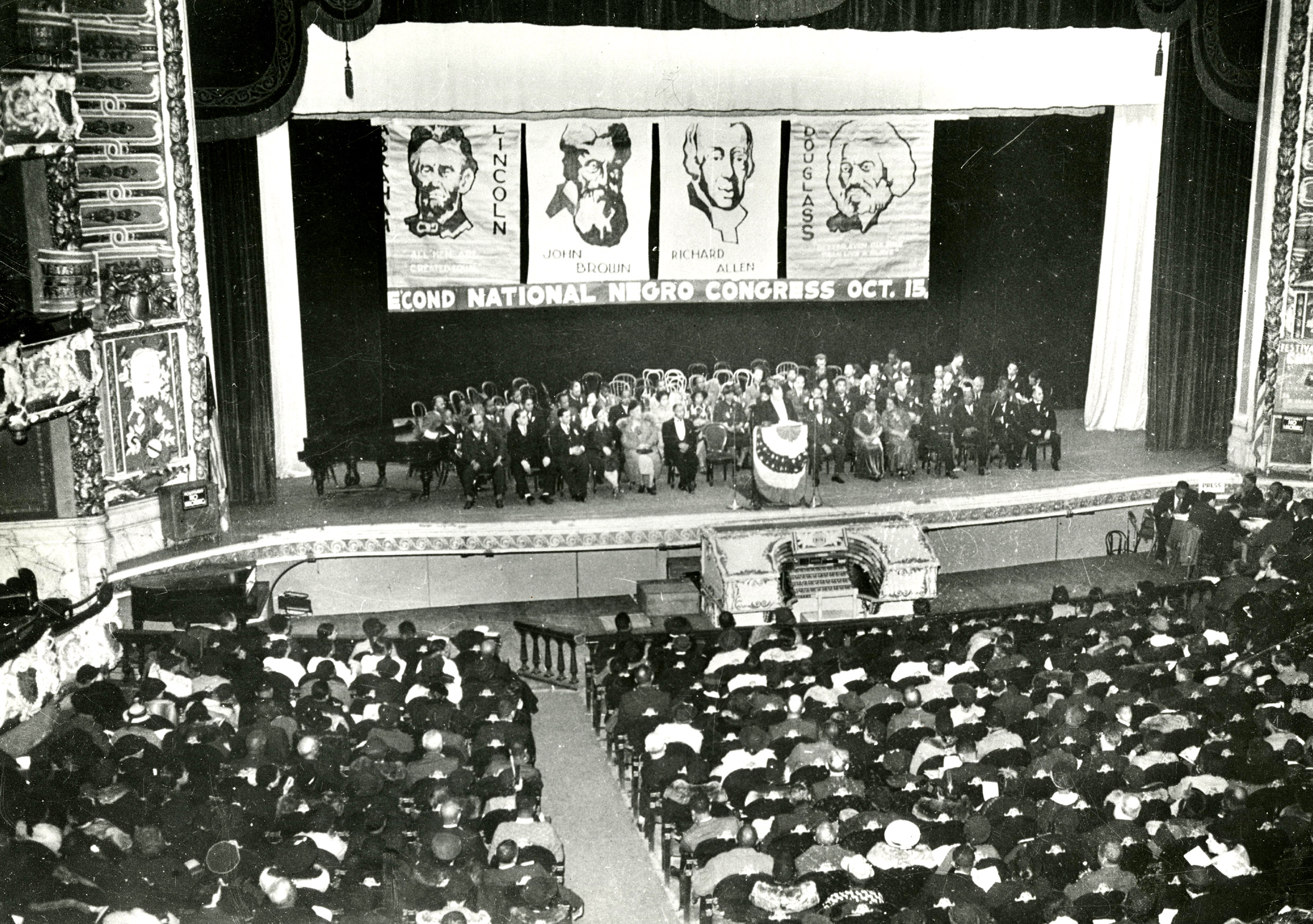

Meeting of the Second National Negro Congress (NNC), Philadelphia on October 15, 1937. The backdrop banners include Lincoln, John Brown, Richard Allen and Frederick Douglass. The NNC was created in 1935 at Howard University with the goal of uniting black and white workers and intellectuals to pressure the New Deal administration for labor and civil rights. It was affiliated with the Communist Party.

ER: I would expect that, like you and me, most people living in the Black Belt today wouldn’t see themselves as members of a distinct nation. They see themselves as Americans.

NP: In fact, they’re the most patriotic section of the country! Is it a mature nation? No, of course not, but I think all the elements are there. The poorest whites and the poorest blacks in the country are in the Black Belt. Of course things change, but have they been able to solve that question? I don’t think so. The most poorly educated, sickest, and most unemployed area in the United States is still the Black Belt. Just look at the statistics. This area is oppressed as a historically- evolved community.

ER: Moving forward to the late 1950s and early 1960s, how did you assess the emerging Civil Rights Movement? Do you think this movement posed a challenge to the Communist movement and did the Communist movement meet that challenge?

NP: The freedom movement was bringing the Civil War to an end. I don’t want to underestimate the subjective factor because I was part of it: the incredible bravery and tenacity of the African-American people, against all odds, to stand up, fight, and suffer the way they did— these are admirable things. But the real motive force was the mechanization of Southern agriculture, driving the blacks off the farm and into the smaller towns, and from there into the major northern cities. This made it absolutely inevitable that blacks would finally win that freedom. Marx points out in Capital, correctly, that you can’t free serfs without replacing them with more productive equipment. The freedom movement was only the political and social expression of the economic revolution that had taken place. Don’t treat it as a subjective question, although it’s expressed subjectively. It’s an objective process!

Tactically, every thinking revolutionary understood that the battle wasn’t over whether or not you were going to support the freedom movement but rather over which wing you were going to support. Were you going to support the black petit-bourgeoisie and their backers? Or were you going to support the emergence— they didn’t get very far—of certain black working-class and lower-middle-class groupings that had a much different view from the right wing (that was supported by the government)? It was a question of how we were going to work with them and what we wanted to get out of it. You have to work with objective reality, but you have to have a program and it can’t be a subjective program. The program had to be based upon the objective, motive forces behind the freedom movement. And the freedom movement was the inevitable prelude to some unity of the American working class. I’m afraid it might come too late. The result is a black president who is probably going to bring a fascist America into being. Is that what we fought for?

Greg Gabrellas: Given this trajectory of the movement for black liberation since the middle-to-late 20th century, how have developments within so-called “black politics” prompted you to reinvestigate or reconsider the problem of race and revolution over the years?

NP: Developments have only confirmed my perspective. If it’s essentially a national question and not a race question then we can expect the development of a national bourgeoisie that is going to be co-opted by the bourgeoisie of the imperial country. This happened in Angola, Algeria, Vietnam, everywhere. Given the development in the United States it was absolutely imperative that an upper stratum of blacks be created and that they be integrated into the bourgeoisie. I wasn’t disillusioned at all by the development of a Colin Powell or a Barack Obama or of black millionaires; these have only confirmed my perspective. Are the black masses any better off than they were before? In Chicago, sixty per cent are unemployed, their brains and bodies wasted. The black bourgeoisie is much better off, but not the black working class. In fact, we’ve lost one of the most precious things we had: our dignity as being “Negro.” We stuck together and we felt responsible for one another. We’ve even lost that.

GG: Granted that the Civil Rights Movement has led us where we are today, in which a small black bourgeoisie is able to make use of the privileges hard won through struggle while leaving behind the majority of blacks in a state of social desperation, a strain of black nationalist thought nevertheless remains more or less univocal in arguing that racism remains the problem of America. How has racism changed over the decades since the Civil Rights movement?

NP: What is racism? Is it cultural? Is it political? We have to come to the conclusion that racism is a political question. Racism in America is color-based, but does this mean there isn’t any racism in Ireland, or between French groupings in France? There is! When I was a youngster, we were taught there were a number of different races. The Mediterranean race of Spanish, Italians, Greeks, and so forth was considered much inferior to the Nordic peoples. Another form of racism in America evolved out of slavery. The point is that they can manipulate this term “racism” any way they need in order to reinforce the economic situation. Right now, we’re seeing a merging of the “trailer trash” and the “ghetto” blacks and the black bourgeoisie goes right along with it. It isn’t as if the black bourgeoisie isn’t just as racist as the white bourgeoisie. What does the black bourgeoisie do for the black worker today? They get as far away from them as possible! Jesse Jackson summed it up when he said that there’s nothing more terrifying than to be approached by three black youth.

ER: In 1974 the Black Workers Congress wrote a polemic against the Communist League and the Revolutionary Union, accusing the latter of “having reached the social- fascist level of recently spreading the imperialist- racist line that the bourgeois nationalism of the oppressed nationalities is the main danger within the U.S. Communist movement today.” ((Black Workers Congress, The Struggle Against Revisionism and Opportunism: Against the Communist League and the Revolutionary Union, May-June, 1974. <https://www.marxists.org/history/erol/ncm-2/bwc-2/index.htm>)) This polemic emerged out of the competition between anti-revisionist Marxist groups for the membership of workers and students. Many groups followed a strategy of theory, unity, and fusion: develop the correct theoretical line, unite revolutionaries behind this line, and then “fuse” these revolutionaries with working people in factories, neighborhoods, and communities of color. What do you make of those who would characterize your criticisms of the black bourgeoisie as "imperialist-racist"?

NP: The black bourgeoisie had to gain hegemony over the black movement in order to accomplish their economic goals and they had to do so on the basis of black nationalism. How else were they going to unite the disparate goals of the black bourgeoisie and the black worker? The black worker’s tendency is to unite with whatever workers are in the plant. The black bourgeoisie’s tendency is to separate the workers in order to gain some kind of foothold in American capitalism. So, yes, I think the black bourgeoisie was and is the most dangerous element as far as the black worker is concerned. The welfare of the black bourgeoisie depends on the destitution and poverty of the black worker. If the black worker became integrated in America then what would the black bourgeoisie stand on? They couldn’t continue to exist.

Most of the contradictions that arose between our group and the other anti-revisionist groups turned on whether or not the goal of the black workers was to fully integrate themselves into the American working class. Of course, they were a part of the working class. I never believed in this “white working class, black working class” business. They were all one working class. But black workers were isolated and subject to segregation. The black bourgeoisie had to maintain that isolation, that poverty of the black masses, as the foundation of their upward development.

The so-called Black Workers Congress was really the black petit-bourgeois congress! They all became professors and small businessmen. What happened to the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, or to the Detroit Revolutionary Union Movement, which was the foundation of this thing? They’re all unemployed, living in Detroit on handouts now. The black worker is still the black worker and the black bourgeoisie is still the black bourgeoisie.

ER: Reading Max Elbaum’s Revolution in the Air (2006) or Mike Staudenmaier’s Truth and Revolution: A History of the Sojourner Truth Organization, 1969-1986 (2012), it becomes clear that various tendencies within the New Communist Movement took up theoretical lines that emphasized black particularity and white privilege. Such theoretical commitments remain widespread among avowedly anti-racist activists and academics on the Left despite critiques of this approach by Adolph Reed and others. What, in your view, was the political result of the lines on race and racism developed within the New Communist Movement? Do you see the widespread emphasis on black particularity as a retreat, politically, from the universalism of the earlier Civil Rights Movement?

NP: I’m quite sure that if the proletarian elements of the African-American movement had been in control there would have been a different kind of political expression. It was petit-bourgeois all the way down, from top to bottom. Exclusiveness is an aspect of petit- bourgeois politics. Just as the British bourgeoisie had to fence off their market in order to develop, so the black bourgeoisie also had to fence off theirs. They had to use the motion of the black masses as their marketplace in order to get these concessions. Look at Jesse Jackson!

Black nationalism was the class movement of the black petit-bourgeoisie against the natural instincts of the worker. When Stokely Carmichael came to the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party with his black nationalism, Fannie Lou Hamer fought like hell for an integrated movement and finally had to resign from SNCC. The Stokely Carmichaels split the movement and by splitting the movement they were able to defeat us. They couldn’t defeat us while we were united and organically connected to the white liberal intelligentsia and to the few workers who supported us. It’s just like a military maneuver: You split the enemy, destroy this section, then destroy that section. That’s what Stokely Carmichael did. This move toward nationalism was first of all in the interests of a black bourgeoisie but it was also indispensable to containing the entire movement. The worst part of it was that the white radicals supported the black nationalists.

ER: Many white radicals embraced separatist approaches to revolutionary organization—and, perhaps relatedly, embraced theories of racial particularity, inter-group oppression, and interpersonal privilege—out of a sense that it would be impossible for an integrated movement to overcome the racism, sexism, and other forms of prejudice that manifested within many New Left organizations. You seem to have built a racially- and gender-integrated organization without adopting theories of racial particularism or interpersonal privilege. To many on the Left today this would seem to be an impossible feat. How has your organization approached internal conflicts over identity and privilege while maintaining this sharp line against black nationalism?

NP: What makes a leader capable of a contribution is that they just happen to have the characteristics needed at a particular time. When I was fifteen years old, I was walking with my father past a guy in the doorway of a tavern, drunk on a Sunday morning. I said, “That’s disgusting.” My dad said, “No! He’s a military genius, there just isn’t any war.” I grew up in Wabasha, Minnesota. Of 1,800 people we were the only black family. Black nationalism never hit a chord with me. I had too many white friends with high moral standards who were ready to die for their beliefs—and these beliefs included real democracy. I was eighteen when I went into the war and twenty-four when I came out. I went to a university for two years on the G.I. Bill of Rights but I finally decided to quit college and become a professional revolutionary. I soon learned that being a professional revolutionary is the same as being a professor or doctor. You have to practice with people who know what they’re doing. Amongst my comrades were people like Joe Dougher and Admiral Kilpatrick, a black worker who taught at the Lenin Institute. Kilpatrick was the political liaison between the Lincoln Battalion and the Fifteenth Brigade, which was the international brigade. These were Communists who spent their lives in combat and trade-union organization. Nobody could hand me this crap about black nationalism.

From the time we established our organization we were debating the question of women. As early as the 1960s, it was clear that the growth of women in the working class meant that they were destined to play a big role in the revolutionary movement. We had to start that training immediately, but we faced the same problem with women that we faced with blacks. We could elect them to office when they were prepared to carry out their duties but that would never happen on its own. So, I finally got a rule passed to the convention that fifty-one per cent of our leaders had to be women. This solved the problem. At the heyday of the Communist Labor Party, we were one third Latino, one third black, one third white, and fifty-one per cent women. Even Elbaum gives us credit for that, writing in a sentence or two that perhaps we were the only organization in the history of the revolutionary movement in America in which minorities and women constituted the majority of the leadership. Fifty-one per cent had to be women and fifty-one per cent had to be a national minority. It was a question of doing it, not a question of theorizing about it. But they’re not capable when you get them, just like nobody is. You’ve got to train them, criticize them, give them history, and insist that they read books.

A gang of black intellectuals has come through our organization. None of them stayed because nobody kow-towed to them. If you don’t submit yourself to the authority of democratic centralism then you can’t stay here. We’ve lost people with great potential who couldn’t get rid of their bourgeois side. They wanted privilege and didn’t get it here. We have a lot of smart black people, but they’re all workers – people like General Baker, the chair of our organization, who formed the League of Revolutionary Black Workers in Detroit.

GG: Based on the political orientation and internal structure you’ve outlined so far, when you formed the Communist Labor Party in 1974 and backed away from inter-group polemics with other New Communist Movement tendencies in order to concentrate on organizing the working class, what obstacles and challenges did you encounter? How do you account for the failure of the Communist Labor Party to organize the working class beyond a certain point?

NP: By that point it was clear that the struggle against revisionism in the Soviet Union had been lost. What lay before us, then, was the question of how to go about the struggle under existing conditions. The Communist Labor Party set about the task of what we call “teaching as we fight,” of putting the question of communism in the context of the history of the American people and of the American social order, not in the Russian or Chinese context.

A new class of people has developed in America by robotics and electronics. More and more people are being thrown out of bourgeois society or are just barely clinging on to it by their fingernails. The Europeans call it a “precariat,” and we call it a “new class.” For the first time, we’re seeing the development of machinery that is making capitalism impossible. The private ownership of the socially-necessary means of production is becoming impossible. But the communist class is ideologically anti-communist. So the role of any revolutionary party today is first of all in the intellectual field. I don’t mean “high intellectualism.” I mean the introduction of ideas that reflect the reality of the new economic situation in America.

GG: Much of the innovative theoretical work that came out of the CLP during the 1970s anticipated the increasing role of science and technology in transforming the character of the working class, in making it harder and harder for workers to organize and for working-class politics to play a leading role in transforming and improving society. What was the role and effectiveness of your intellectual grasp of these wide-ranging social transformations—what was the payoff, to use a very vulgar term, of your theoretical work—if you were still unable to make the most of the historical development that brought us where we are today?

NP: What is the revolutionary process? Essentially, it’s that the spontaneous development of the means of production—the economic revolution—produces a social revolution, creates a crisis. It begins with the destruction of the existing society. We’ve been in that situation for twenty or thirty years now. We’re seeing the destruction of one social order by the economic revolution. The contradiction between the old social order and the new economic order is eventually going to bring about a political revolution. That political stage is only a small part of the revolutionary process. The revolutionary process itself is a social revolution. So, under these conditions, any revolutionary who deals simply with the working class is not being serious. The working class is over with. You have to deal with society, with the social upheaval developing in America.

ER: What are the political implications of your concept of a “new class”?

NP: Any dictionary will tell you that a political party is a subjective expression of an objective process in society. In Entering an Epoch of Social Revolution (1991) we pointed out that the critical weakness of the world communist movement up to this point is that there have been communist parties (and they have had the ideology of Marxism) but there has never been an actual communist movement that these parties can represent. The Democratic and Republican parties weather these storms because they represent an actual motion in society—that is, the capitalist system is real, and they represent that! There’s a class in society that is capitalist! There has never been a socialist or a communist class—up until this point—because there has never been machinery, means of production, that will allow for the creation of that class.

We can mark the evolution of capital with the development of manufacturing. When manufacturing reached a certain point, capital became possible. Someone came up with the idea that instead of buying a person and enslaving him for life he would get much more out of him with the wage system. There was a practical motion towards the evolution of capital before there was a political movement for capital. The political movement sprang out of the practical movement. That is not true with the communist movement. In Russia, Stalin and Lenin wrote over and over again about the Russian proletariat being the most revolutionary in the world—but they never called that working class “communist” because they could not be.

Today we’re faced with machinery—productive equipment—that does not require human labor anymore. It’s accelerating. We’re looking at the practical possibility, within my lifetime perhaps, of the majority of labor (and a lot of intellectual labor) being done away with by electronics. How are people going to eat if one section of society owns the productive processes and the other side has nothing to sell? The only way that the majority of people can survive is if these marvelous means of production belong to society, the resources of society are distributed by need, and the individual contributes to society whatever he or she is capable of. We see the possibility of an actual communist class developing for the first time in world history. A different kind of communist party has to represent that. Every communist party in the past has been based on ideology. The Communist party that must evolve out of this practical situation has to be political, not ideological—not that ideology doesn’t play a role, of course it does! But the salient task of the party is going to be the pathbreaking and practical development of the communist society. In the same way, the task of the Republican Party was to break open the path for the practical development of modern industry based on the steam engine.

ER: It seems that much of your work, especially coming out of the 1970s, 80s, and 90s, suggested that capitalist society has never yet been “ripe” for communism and that any revolution seeking communism has been “premature.” I want to play devil’s advocate. Lenin might have thought that if a revolution had succeeded in his lifetime in Germany, England, or the United States, then conditions might have been made ripe for communism fairly quickly. Likewise, Trotsky wrote in the late 1930s that “All talk to the effect that historical conditions have not yet “ripened” for socialism is the product of ignorance or conscious deception. The objective prerequisites for the proletarian revolution have not only “ripened”; they have begun to get somewhat rotten.” ((Trotsky, Leon, The Death Agony of Capitalism and the Tasks of the Fourth International, May-June, 1938. <https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1938/tp/index.htm#contents>)) This was during the Great Depression, a period of mass unemployment that many associated with labor-saving advances in production. This would seem to signal that the “objective conditions” were ripe for socialism by the beginning of the 20th century, if not earlier, and that socialism did not fail on account of insufficient productive forces.

NP: No matter how bad the situation was in the U.S., the reality was that about two-thirds of the world—Asia, Africa, Latin America—was still ripe for expansion within the capitalist system. But they had to get rid of the closed colonial system. Looking back, the war against Hitler was essentially a war against this closed colonial system. It was a war against England, against France, against Germany, against all of the colonial forces. Hitler was only the worst of them. The Second World War was about whether global finance capital or global industrial capital would be in control. Japan, Germany, etc., represented the past. Roosevelt represented the future. Today we’re seeing the completion of the capitalist consolidation of the world. This is a dangerous thing to say, but I don’t think there’s anywhere for capital to expand.

ER: Are we really reaching the limits of capitalist expansion today? Jobs are still being automated across the world—in the U.S. alone, tens of millions of jobs stand ready to be automated based on current or near-future technologies—while people continue to be proletarianized across the world. But it’s easy for us to imagine that the slum conditions of much of humanity will simply persist and expand as these processes occur, leading to more of the same and worse. What would it mean to complete the social revolution?

NP: One of the most important elements in dialectics is the relationship between quantitative development and qualitative change. If you don’t have a nodal line or nodal point—a point where quality changes—then everything becomes quantitative. In Entering an Epoch of Social Revolution I was trying to say that, since capitalism is based on wage labor and the intensification of the labor process, it is in the interest of the capitalist system to constantly improve the means of production, to make wage labor more productive. But the nodal line is reached when machinery replaces wage labor rather than assists wage labor. Every day more and more of these labor-replacing devices are coming on the market. Cisco is advertising an assembly line that repairs itself. You can’t tell me that self-repairing robots are labor-assisting devices! There isn’t one person on that assembly line. It’s no longer capitalism when you have done away with wage labor. Cisco’s going to make money, but the money is going to be worthless, because money represents labor! The whole thing is headed for collapse. Revolution isn’t one act; it’s a whole epoch. It’s not an uprising but a process of economic revolution to political revolution to social revolution to the end of the social revolution through reconstruction.

The Communist Party USA usually thinks it’s better to ignore us but every now and then they’ll take a whack at us. They insist that electronics is nothing but another quantitative stage of development of capitalist industry. Our position is that a device that replaces the worker is qualitatively different from a device that assists the worker. It’s not a question of ideology, of what I think. It’s a question of objective reality.

ER: Wal-Mart has developed one of the most advanced automated distribution systems that the world has ever known. It’s almost the sort of distribution system that some were hoping would emerge out of the Soviet Union (as opposed to the more bureaucratic distribution system that did in fact exist under 20th- century socialism). Yet much of the U.S. left fails to recognize how much emancipatory potential there is in such technologies. Of course, in order to tap this emancipatory potential, we would need to organize society very differently.

NP: I’m with Marx on this: we rejoice with every single technological advance because it makes the revolution more inevitable and brings it closer. Just imagine the paradise we can create!

ER: Your approach to the societal implications of recent technological changes seems somewhat similar to that of the futurist author Alvin Toffler. When I first encountered Toffler’s work I had no idea that he had a background in the CP. Have you engaged Toffler’s thinking?

NP: I was in the same club with Al for about a year and a half in Cleveland! We were friends and comrades. When the Party made the call for as many people as possible to quit school and work in industry to re-establish the Party’s base in industry, Al and Heidi Toffler left lucrative and important positions to work in steel mills. This was around 1949-51. By 1951 it was clear that Al had serious differences with the CP. Then he got drafted and went to Korea. When he came out he never got back in touch with the movement. At that period of time the Party was beginning to fall apart. A lot of people were striking out for themselves. Al began writing for some futurist groupings. Then he came out with his first big book, Future Shock (1970). The Third Wave (1980) was of great importance. I have my differences with the “third wave”—we’re not dealing with the third wave, but with something on par with the conquest of fire, a whole new epoch of human history—but when Al wrote The Third Wave it was way ahead of the thinking of most people.

ER: Do you consider Toffler a Marxist?

NP: Al utilizes some aspects of Marxism but I’m not sure that I would call him a Marxist. The Third Wave is no contribution to the revolutionary movement; it’s a disorientation. Given Al’s intellectual development, he could have been another Karl Marx, but he chose not to be.

ER: In Black Radical, you describe how “The sense of loyalty and the desperate need for unity was easily transposed into weapons that intellectually deadened and threatened to destroy the Party.” Considering the trajectory of ex-Communist intellectuals such as Toffler, how chiefly would you rank this intellectual death among the causes of the Party’s failure?

NP: I want to make a distinction between Communists and those who struggled alongside Communists. During the Spanish Civil War, for example, a large number of intellectuals joined the Lincoln Brigades to fight against fascism in Spain. They weren’t fighting for communism, they were fighting against fascism—but they could only do so under the leadership of the Communists because no one else was leading that fight. I could name hundreds of similar examples. The singer and actor Burl Ives summed it up when testifying before the House Un-American Activities Committee. They asked, “Why did you sing in front of the Communists?” and he replied, “because nobody else would listen to me!” The Communist Party opened the doors for thousands of cultural workers, especially among minorities and the black cultural intelligentsia. Later on a lot of them became anti-Communist because they knew where their bread was buttered.

GG: The 1930s are often seen as a high-water mark for politics on the Left: sit-down strikes, homeless people’s demonstrations, the Popular Front, the New Deal, and the hegemony of the Communist Party in social and artistic movements. But if the Party was in dire straits by the 1950s, how was this crisis already manifest in the 1930s? Was the 1930s both a high point of the Left and a period of profound Communist Party mis-leadership?

NP: The rise of fascism was the most dangerous thing at that time, not only to the Soviet Union and communism but to the common people of the world. The Third International was correct in taking the position that everything had to be subordinated to the destruction of fascism, that we couldn’t achieve anything until fascism was destroyed. But the American party applied this very mechanically. Earl Browder, the chair of the CP, was imprisoned for a petty violation of his passport. Roosevelt pardoned him, took him out of prison, and had dinner with him. When Browder left the White House, Roosevelt had the Communist Party in his hip pocket and that meant Roosevelt had the left wing of the CIO, and everything that was influenced by it, in his hip pocket. The Communist Party dropped a good number of things they should not have dropped in order to remain a hidden but very influential sector of the Roosevelt coalition.

But it’s intellectually dishonest to condemn people fifty years later for things which they had very little choice. The CP was under intense pressure; the anti-Communist violence in the United States during the 1930s was very serious. People were being lynched for being labor organizers. There was a role for the CP and it played that role. The CP put up fronts, organizations like the Civil Rights Congress, itself made out of five other civil rights groups. The Scottsboro Boys, Angelo Herndon, Rosie Ingram—the CP stood at the forefront of these struggles. Practically all of the slogans of the Civil Rights Movement, and many of the goals, originated with the Communist Party. But they had the wrong conception of the “Negro question” and they therefore came to the wrong conclusions about how to approach it.

GG: Yet many who were in or near the Party and who later played a role in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s, including people like Bayard Rustin, Ella Baker, and even Richard Wright, became anti- Communists, suggesting that there was something about the politics of Marxism in 1930s America which, while heroic in its fight to combat the fascists, ultimately led to a broader depoliticization. What accounts for this ambiguity within Communist politics in the 1930s—that it was both the highest expression of American Marxism, but also the turning point against which American reaction still stands victorious?

NP: The high point of the CP’s influence was really during the war. Certain doors were opened because of the alliance with the Soviet Union against Hitler; the pressure against the CP was eased off to some extent. But during this period, the CP began losing its working- class base. The Party was inundated with a petty- bourgeois strata, especially the cultural intelligentsia. Later on the United States government simply bought them off. The CIA put out a book entitled The God That Failed (1949), full of ex-Communist writers who were paid immensely to take this position. Richard Wright is a good example. During the 1950s it was murder—you couldn’t earn a living! If you were a professor, for example, they told you, “Either you’re going to sign this anti-Communist oath or you’re not going to keep your job.” The same applied in the labor movement. The CP had control of 11 or 12 international unions, but the labor leaders were told, “If you intend to use the Labor Relations Board for negotiations, you’re going to have to sign the anti-Communist oath,” and they had to take that position against the Party. Doing so, they had to justify it, and the justification was generally rotten.

Now, there were some people who had some genuine gripes against the Party. My differences with the Party were based on internal legality. As the pressure against the Party increased, it became necessary for decisions to be made by a very small group of people, on-the-spot more or less. This tendency to have people not responsible by law to the apparatus arose out of necessity and finally ended up destroying the Party. It was expressed by the ability to throw people with whom you disagreed out of the organization. But I was not like the intellectual Howard Fast who claimed, “Stalin fooled me.” Stalin didn’t fool me! Whatever I did, I did with a clean conscience. This idea that somehow the Russians brainwashed them and Stalin lied to them is nonsense.

ER: On what basis did you criticize the Party in the 1950s? What made you decide to leave?

NP: The critical change was that the CP became a party of anti-fascism rather than a party of communism. Not that I think communism was possible—nothing like that!—but the Party should have been guided by the contradiction between the productive forces and the productive relations rather than the contradiction between fascism and democracy. Several things laid the foundation for this. The Jews suffered terribly, as is well known, under the fascist system. The Jewish section has always been a very powerful element within the Communist movement. They have provided the thinkers. At the end of the war, about seventy per cent of the CP was Jewish, concentrated heavily in the New York area, and I would say about fifty per cent of them were more anti-fascist than they were communist—but the Communist movement everywhere was leading the fight against the fascists.

By 1944-45, the Roosevelt coalition had become the heart and soul of the CP. I was one of the people arguing that we had to have a party based on a scientific evaluation of the evolution of society and not at all based on the question of anti-fascism. The question of anti-fascism is tactical, not strategic. I was fighting for the orthodoxy but the vast majority of the comrades accepted this revisionist compromise, even to the extent that a section of the CP declared that the Roosevelt coalition would lead the world to socialism. The financiers are going to need you in the struggle against the industrialists, but how is that going to lead to socialism? Looking back, you can’t believe that serious people believed that! At the same time, people high up in the U.S. government, in the scientific community, and in academia were “talking socialism”—not necessarily Soviet socialism, but an orderly society rather than the jungle.

I fought what I considered to be a principled fight. I was expelled without charges or trial. I joined a group of others who had either walked out of the CP or had been expelled and who were trying to form another CP. This was the Provisional Organizing Committee. These were primarily people who had been minor officials within the CP. (But some of them weren’t so minor. The head of the organization, Joe Dougher, was the military commander of the Lincoln battalion in Spain and was head of what we called the “Iron Triangle” unit: Pittsburgh, Chicago, Detroit, the heartland of the industrial working class in the United States.) The POC was marginalized. Nobody talked about it: not the press, not the FBI, not the CP. They killed it with silence and it finally degenerated, splitting into three or four different factions.

ER: Given your criticism of the Party’s orientation to the Roosevelt coalition, why wasn’t Trotskyism a live option for you in the way that anti-revisionism was? Many American Marxists saw Trotskyism as stillborn by the postwar years but some continued to flock to its banner.

NP: In the Communist-influenced movement you didn’t talk to Trotskyites and you didn’t talk to people who did talk to Trotskyites. I once asked one of the leading Trotskyites about their early relations with the fascist movement. They told me that nothing could be done until the Russian regime was destroyed. That set me against them forever! The Communist movement was fighting for something that was attainable. The Trotskyite movement was fighting for the same goal but they were fighting for it all at once and it was not tactically attainable. Consequently, they formed an extreme Left and split the movement.

ER: With a politics reminiscent of the CP during the Popular Front years, some veterans of the New Communist Movement (such as Carl Davidson) have argued for some time that leftists ought to work within the left wing of the Democratic Party—within organizations like the Progressive Democrats of America—to “fight the right,” to raise political consciousness within such organizations, and to potentially play a role in the eventual formation of a leftist third party that would split the Democrats. Lenny Brody and Luis Rodriguez, former members of LRNA (your organization), have been working with the Justice Party to this effect. What do you make of this strategy?

NP: The old slogan of the First International is the correct slogan: “To the forge, comrades, and strike where the iron is hot!” We should, to the extent that we’re capable, be where the social motion is. We should also not be there just because there’s activity. We should be there as part of a general plan based on a scientific understanding of how a political process plays out. The social process is that the capitalist parties begin to split tactically over how to achieve their various goals. A third party begins to emerge out of these splits. I take the defeat of Kucinich as a very important step along this way. The Barney Franks and the Kucinichs, who left the Democratic Party in disgust or who have been defeated, are coalescing towards forming a third party that will do properly what the Democratic and Republican parties aren’t able to do. We’re a very small organization; we don’t have the cadre to really make any impact on this. The American left is not going to impact anything! The impact is going to come from the liberal sections of the intelligentsia and certain sections of the bourgeoisie who see the danger of going in the other direction. They’ll form a third party, and it might have progressive talk, but it’s not going to have any progressive activity. It will mean the end, though, of the total domination of the working class by the two parties. It will be the last gasp of the bourgeois-democratic political process but it’s an absolutely inevitable one. We have to go through it. Out of the struggle for the third party we’ll create the conditions for a workers’ party. To that extent, on a tactical level, I’m all for it! But these people out of the New Left greatly overestimate their importance.

ER: Given that Brody and Rodriguez are part of a larger group of New Left-generation cadre that has recently left LRNA to form the Network for Revolutionary Change, and that some of these ex-LRNA cadre are playing leading roles in the formation of the Justice Party, why did they take a different direction and leave LRNA?

NP: There are two foundations for revolutionary movements. One is the objectivity of capital, the struggle that arises from the contradiction between productive forces and productive relations, and the subjective ideology that solves this problem. The other is the spontaneous reaction to oppression that arises from social conditions. Which side do you want to be on? Like most of the New Left, they want to be on the side of the spontaneous reaction to oppression, but that’s inevitably going to have plenty of organizers anyways. If they want to contribute to that, OK—but turn us loose! A faction of about ten people quit when they couldn’t get what they wanted. They’re a grouping primarily around Luis Rodriguez who got the idea that powerful individuals determine what happens in history. They’re based on the nationalism of the Latino movement and of the black movement coming out of the 1960s and 70s. We didn’t base ourselves on the African-American movement and we got some very good people out of that: 178 people joined us from the Detroit Revolutionary Union Movement. They were all black nationalists. When we told them who we were and how we functioned they stopped immediately with their black nationalism and became real communists. They still are! They were the spontaneous movement. We worked with them but we didn’t base ourselves on them or worship them!

ER: What do those who have left LRNA want to do that wouldn’t be possible for them to do in LRNA?

NP: A complicated example is what happened in Madison and what is happening in Detroit. In Detroit, you have a political fascist offensive, not an economic struggle. Madison is a trade-union struggle. It’s important, but very limited—a question of maintaining their rights. They say that the trade unions are important. The trade unions have never been important! I’ve been a union bricklayer all my life—I have more trade-union experience than any of them—but in the revolutionary movement the unions cannot, never have and never will, play any decisive role, because they’re an integral part of the capitalist system. I went into the Steelworkers for the Party. The Steelworkers had a mixed union and the union had a clause that blacks could not rise above the labor gang. The employers were not our problem—the union was! The petit- bourgeoisie worships this ideology of spontaneous union action without any consideration of the history of American unions. The biggest obstacle to communism in the world has been the American unions! Look at Walter Reuther and David McDonald.

ER: Why then did Marx decide to become involved with the British trade unions during the 1860s and form the First International? How should a Marxist recognize the reformist character of trade unions while keeping in mind Marx’s own involvement with unions at certain times?

NP: Marx was very self-critical about his position on unions. Engels especially was. They thought that unions were somehow an incipient form of what communism was going to be, the workers learning how to run a government by learning how to run a union. They finally concluded otherwise. Unions play a certain role in intensifying a social struggle, but as far as a class struggle is concerned—that is to say, the question of political power—they’re never going to be able to do anything because they’re such all-inclusive organizations. It’s interesting to note that the first victim of the Soviet revolution was the transportation workers’ union. They struck against Soviet power and Lenin crushed them! The revolution in the United States is going to come from the contradiction between the revolutionary character of the productive forces and the stability of the productive relations, not from the unions.

ER: Speaking of the politics of the labor movement, how do you assess the accomplishments and ultimate failure of the U.S. Labor Party?

NP: I once had a short talk with Tony Mazzochi, the head of the party, around the time of its formation. I told him: We’re all for a labor party, and if you want to head that party, we’re going to stand behind you. But we warn you in advance: Conditions are not ripe! You’re going to end up with a trade-union party and that can’t survive. You have to go through a process in which a bourgeois third party emerges and fails; then you’ll have an opportunity. What we warned them about and predicted was exactly what happened! It became a trade-union party and then it collapsed.

ER: Yes, and it collapsed largely over the question of how to approach the electoral arena in the 2000 election, over how to approach not only the Democrats but also Ralph Nader and the Greens.

NP: The experience of the Progressive Party taught me these things. The greatest people in the world were in our leadership, including from the trade unions. At the time of the formation of the Progressive Party, the Communist Party was in control of 11 international unions and a huge section of the African-American movement. People of the very best caliber, like DuBois and Robeson, were close to or in the Communist Party. Even the anti-Communists like Henry Wallace would not red-bait anyone; Wallace was scared of the CP and he didn’t move against them. A section of the liberal bourgeoisie was terrified by Truman. There was a moment of possibility. But the reality was that America had the possibility of taking over the entire devastated and starving world. How are you going to form a party against expansion, against wealth? As Marx said, prosperity is the death of a revolution. What we’re seeing today that we couldn’t see in 1948 is a fundamental shift in the productive process, perhaps the greatest social revolution there has ever been: destroyed neighborhoods, shuttered factories, kids standing on the street with no past and no future. The first phase of a social revolution is the destruction of the old society. Our society is being destroyed! Does there have to be a political change to express this? Of course! The first change is going to be the attempt of the petit- bourgeoisie—the Kucinichs—to hold this together on a different level. They’re going to be part of a third party. The Left is going to jump in that party and do exactly what they did with the Progressive Party: They’re going to become absolutely alienated from revolutionary activity because they can’t afford to destroy what they’re creating.

ER: Given that you view the League as a propaganda organization whose purpose is primarily educational, what would success look like in the present?

NP: This was one of the bones of contention within our organization! Any organization of professional revolutionaries is an organization of propagandists. Is the main obstacle to revolutionary development in America today not the political and intellectual backwardness of the American working class? Can anything be done with a working class that’s anti-Communist? Is our first task not to win them away from the bourgeoisie ideologically? Lenny Brody believes that if we fan the flames they’ll learn. I’ve been a Communist for seventy-two years and I’ll tell you that they’re not going to learn from experience! Marx and Engels were clear about this: The most revolutionary weapon in the world is the human mind. If you don’t win that, you’re not going to win anything.

What we’re doing now couldn’t be done before in American history. Anyone my age will tell you that the anti-Communist movement in America was anti-black. They hated the Communists because of their demand for equality for blacks, for integration. The American people couldn’t be won to communism because of the race question. So it became part of American Communist history to simply deal with the spontaneous movement and not with the ideology. But the upheavals of the 60s were fights to get into the capitalist system, not out of it. The blacks welcomed the Communists for their fighting capacity, for their morality, but they totally rejected them for their ideology. It’s easy to glorify these movements, to make them into what you want them to be, but history doesn’t allow you to do that. The American people are going to suffer before they come to the conclusion that they have to unite around the objective reality of the American economy. This reality demands that we take over the economy and run it in the interests of the American people. It can no longer be done on the level of private property. |P

Transcribed by Joseph Estes.