Marx’s liberalism? An interview with Jonathan Sperber

Spencer A. Leonard and Sunit Singh

Platypus Review 58 | July 2013

On June 25, 2013, Spencer A. Leonard and Sunit Singh interviewed Jonathan Sperber, historian of the 1848 revolutions and author of the acclaimed new biography Karl Marx: A Nineteenth Century Life (2013), on the radio show Radical Minds broadcast on WHPK–FM (88.5 FM) Chicago. What follows is an edited version of the interview that was conducted on air.

Spencer Leonard: Let me start off by asking a very general question. As indicated by the book’s subtitle, this is a “19th Century life”: You are placing Marx in his context, and claiming that Marx is not our contemporary, but best understood within the 19th century, a century you view as both fading into the past and distinctively still with us. So, if Marx is more a figure of the past than a “prophet of the present,” one could ask, Why bother writing a new biography of him?

Jonathan Sperber: In his history of the 19th century, The Transformation of the World, Jürgen Osterhammel argues that the 19th century is sometimes extremely close to us, but more often it is very distant. That’s how I look at Marx. There are ways in which he seems relevant to present concerns, but most often when we look at his writings—stripped of their 20th century reinterpretations—we find Marx is dealing with a different historical era than our own, with different problems and different issues. Though he uses many of the same words, like “capitalism,” this means something very different from today’s global capitalist economy.

Sunit Singh: When Marx confronted the possibility that a university career might be closed (once Friedrich Wilhelm IV initiated a rightward, anti-Hegelian shift in Prussia around 1840) Marx turned to work as a journalist and editor. You describe Marx the crusading young newspaperman as follows:

Marx blasted [the] enemies [of the freedom of the press], linking their arguments to an archaic society of orders, to an authoritarian Prussian state trying to prop up this society, and to intellectual trends defending it…. [He also set about] praising freedom of the press as part of a broader encomium of freedom, articulated in opposition to the nature of the Prussian monarchy… [and] the debates on freedom of the press in the recently concluded Rhenish Provincial Diet…. Marx brought together liberal aspirations for an effective legislature, and for a constitution guaranteeing basic rights, such as freedom of the press, and liberal hostility to the society of orders…. [Marx argued] in Hegelian fashion, [for] a free press as the objectification of the people’s spirit and not an objectification alienated from its spirit, but one that knew itself as such (83-87).

As editor of the Rhineland News, Marx adopted a “liberal, anti-protectionist, and even anti-communist stance” that the “bourgeois liberals who were financing the newspaper” could rally around. Moreover, this commitment to free trade or even his criticisms of communism were, on your account, not the ideas of a liberal youth that Marx would later discard. So what were Marx’s formative political experiences and how does a Nineteenth Century Life reframe our understanding of them?

JS: I’ll mention four places where I show Marx’s formative political experiences. One was his relationship with the Prussian monarchy. Marx was born in Trier, a city that had been annexed by Prussia by the time of the Congress of Vienna. Its inhabitants were deeply hostile to Prussia. Marx himself was profoundly ambivalent towards Prussia. Nevertheless, as a Young Hegelian, he looked to it as a source of liberalism, reform, and enlightened ideas. However, he would ultimately become a strong enemy of Prussia. This break with liberal illusions about Prussia was formative for Marx. It led to him becoming a radical, who saw the resolution of political confrontations in violent revolution. Then, there are the ideas of Hegel, which shaped Marx’s views of historical process, and social and political struggle. Third, was Marx’s confrontation with the ideas of classical political economy in the form of figures like Adam Smith, and Smith’s most important disciples, such as David Ricardo, and James and John Stuart Mill. We see this in a very early form in Marx’s advocacy of free trade, which was something he maintained throughout his life. Although Marx, of course, broke with nineteenth century pro-free-market and pro-private property liberalism, becoming a communist, he did so while retaining the basic tenets of classical political economy. Marx always criticized socialist thinkers like Proudhon, who tried to prove Ricardo wrong. (This was one of the central points of Marx’s critique of Proudhon in his polemic, The Poverty of Philosophy.) Finally, there is Marx’s confrontation with the French Revolution, the dominant political event of the first two-thirds of the 19th century. The revolutions that Marx the radical advocated were modeled on those occurring in France in 1789 and 1793. These were Marx’s formative political experiences. His developed theory was an attempt to combine all four into a cohesive view of the past development and future trends of European history. This developed theory reminds me a little of what happens when you put a cat into a box. Cats like boxes, and they often climb into them even if they aren’t big enough. No matter how much they contort their bodies, there’s always some part sticking out. Marx’s effort to combine all of these influences into one theory strikes me as very much like this.

SL: While editing the Rhineland News in Cologne, Marx criticized many of his fellow Young Hegelians for their foppish “lifestyle-based radicalism.” How did this critique of bohemianism develop into more politically pointed criticisms of fellow socialists in Paris and Brussels?

JS: What Marx disliked about the Young Hegelians was the way their interests revolved around carrying on an atheist lifestyle, making fun of established religion and gender relations. When Marx became a newspaper editor, and began to hang around with businessmen and politicians who were actually trying to change things, he began to see the Young Hegelians as a frivolous lot and their efforts as non-serious, as leading to no changes in state and society. This attitude was expanded and developed in his various critiques of fellow socialists in the 1840s, such as Proudhon and Karl Grün. Marx criticized them for trying to smuggle communism into existing capitalist society by making it a lifestyle choice (e.g., by joining workers' cooperatives or Fourierist phalansteries) instead of seeing it as a political issue involving revolutionary social struggle. So Marx developed this critique of the lifestyle-based politics of the Young Hegelians into one of communists skeptical of political struggle. They saw the implementation of communism as a matter of changing people’s opinions and social habits, rather than of overthrowing the government.

SL: They thought if people’s ideas changed, political change would follow?

JS: Yes, but in that case political change would become unnecessary. If people’s ideas changed, then there would be no problem. Marx was well aware that people’s ideas must be changed, but he saw such change as being effected through political struggles.

SS: You argue that Marx’s developing worldview in the mid-1840s is perhaps best captured by his articles, “Introduction to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Law” and the review of Bruno Bauer's “On the Jewish Question,” both written for the Franco-German Yearbooks. The two articles represent his attempt to digest Hegel’s theory of modern society after the collapse of the society of orders and, despite this collapse, the apparent antagonism between the state and civil society. While the rhetoric of, especially, “On the Jewish Question” has forced “Marx’s defenders [to] tiptoe around the essay in embarrassed fashion” (127), you take Marx’s engagement with Bruno Bauer over Jewish emancipation to mark a crucial stage in his development as, so to speak, a late Hegelian. How did Marx’s position in these pieces mark a real crystallization of his thought?

JS: As far as Marx’s review of “On the Jewish Question,” in the second part in particular, Marx really lets loose on Jews, accusing them of being greedy, selfish, and capitalistic. He claimed that in a communist society, Judaism would no longer exist, and Jews would no longer be an identifiable group. Seen from the point of view of the 20th century, with the Nazi and Stalinist persecutions of the Jews, this is very embarrassing. Indeed, many have denounced Marx as an anti-Semite and a proto-Nazi. One of the things I argue in the book is that this is a false perspective on the essay. What we actually see here is Marx making a very interesting distinction between what he calls “political emancipation” and “human emancipation.” He argues that the emancipation of the Jews would involve granting them equal rights with Christians and the creation of a society like in the United States with a separation between church and state, which marked a crucial step in the completion of the program of the French Revolution.

Now if Marx had stopped there, no one could have accused him of being an anti-Semite. But Marx believed that the completion of the program of the French Revolution (the creation of a democratic republic, a society in which people were equal under the law, an end to discrimination on the basis of religion or race), while a historic step forward from the old regime society of orders, itself created a society marked by alienation and capitalist exploitation. So, in the second part of the essay "On the Jewish Question," the part which tends to offend people, he went on to argue that true human emancipation requires an end to this capitalist society of alienation, exploitation, and the separation of state and society. This is the beginning of his Hegelian argument for the creation of a communist regime. It seems in some ways an odd argument. Marx was saying that Jews needed to be emancipated in order to act freely as members of civil society, but that when they do that, the moneyed among them will simply end up as capitalist exploiters. So the question becomes: Why would you bother doing this in the first place? What was Marx talking about? And this becomes a central element of his political aspirations, a dilemma he would wrestle with for the subsequent 40 years: How would it be possible to do both, to complete the tasks of the French Revolution by overthrowing monarchies and creating democratic republics and societies of equal citizens, but also go beyond that by creating a communist society in which alienation was abolished, and society, the state, and individuals were harmonized. Trying to carry out these two revolutionary acts at once turned out to be impossible. Marx never found a way to resolve this issue.

SL: One major theme of Karl Marx: A Nineteenth Century Life is that, as you have indicated already, Marx understood himself as heir to the French Revolution. Specifically, Marx expected and, indeed, in perhaps the most famous passages of The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, described 19th century revolution as a repetition of the 18th century French Revolution, particularly in its 1789–1794 phase. Thus, Marx simultaneously longs for the revolutionary poetry of the future, even as he argues that the past necessarily recurs. You describe Marx’s thinking at the time of the Revolution of 1848–49 as follows:

Using his influential position within the newly reorganized Communist League… Marx took scant time to join the revolutionary fray. For a little over a year, from the spring of 1848 through the spring of 1849, Marx was, for the first and last time in his life, an insurgent revolutionary: editing in brash, subversive style the New Rhineland News; becoming a leader of the radical democrats of the city of Cologne and of the Prussian Rhineland; trying to organize the working class in Cologne and across Germany; and repeatedly encouraging and fomenting revolution. In all of these activities, Marx persistently promoted the revolutionary strategy he had first envisioned in his essay on the Jewish Question, and would present in scintillating language in the Communist Manifesto. He pressed for a democratic revolution to destroy the authoritarian Prussian monarchy. At the same time he aspired to organize the working class to carry out a communist uprising against a capitalist regime he expected such a democratic revolution to establish. In effect, Marx was proposing a double recurrence of the French Revolution: A repetition of its 1789–1794 phase in mid-nineteenth century Prussia, and also a workers’ seizure of power… (195)

And, again, when you come to address the Manifesto itself, you note the magnetic influence of the French Revolution upon its programmatic aspect. “The ten-point program in the Manifesto,” you write, “was designed for a revolutionary government, one modeled on the radical, Jacobin phase of the French Revolution in 1789” (210). How and why does Marx, who is after all, the great theorist of modernity’s historical dynamism, also view history as subject to this sort of repetition such that he expects the French Revolutionary past to return under changed conditions?

JS: Maybe we need to revise our notions about Marx’s attitude toward modernity’s historical dynamism. Marx’s political thought—like most of his contemporaries’—was centered on the French Revolution. This was just a reality that dominated the first two-thirds of 19th century Europe. When people thought about politics, they thought about it in terms of the French Revolution. Marx was no exception in that respect. What’s interesting about Marx is this idea of what I like to call the “double recurrence” of the French Revolution. On the one hand, the French Revolution would literally recur in Central and Eastern Europe, with an uprising against the Prussian and Austrian monarchies and their replacement by a revolutionary German Republic. This would probably include a revolutionary war against the Tsar—a literal rerun of 1793 in mid-19th-century Germany. But there would also be a recurrence by analogy. That is, Marx saw the bourgeoisie as seizing power, bringing the feudal society of orders to an end, and replacing it with a capitalist economy. By analogy, the workers would do the same thing: They would overthrow capitalism and create a communist society. Marx wants to do both at once in 1848, but he finds it very difficult. He discovers, in trying to overthrow the Prussian monarchy, that you can’t get the workers riled up against the bourgeoisie, because the bourgeoisie then won’t support you in overthrowing the monarchy. In his speech to the Cologne Democratic Society in August 1848, he ends up describing the class struggle as nonsense. The problem was that organizing the workers against the capitalists did not necessarily mean opposing the Prussian state.

SL: What I meant by Marx as a thinker of historical dynamism is the way that Marx thinks about industrialization as producing constant historical change. It is in this respect that the 19th century looks different from the 18th century, the century of the French Revolution. In this sense Marx is quite conscious of holding on to the French Revolutionary conception of politics under vastly changed circumstances.

JS: I really think that Marx here is a primarily backwards-looking figure, who is reading capitalism’s future out of its past. He sees the future political crisis of capitalism being resolved by a movement along the lines of the French Revolution. His whole economic vision of the future of capitalism (e.g., the labor theory of value, the falling rate of profit) is based upon the ideas of David Ricardo, who wrote in the early 19th century, the earliest phase of the Industrial Revolution. Marx saw these conditions, which by the mid-1800s were capitalism’s past, as being capitalism’s future. All of Marx’s invocations of dynamism and constant change—we all know the famous (and actually mistranslated) section of the Communist Manifesto proclaiming that “all that is solid melts into air”—tend to end up parsed in terms of Marx’s past.

SS: Could you provide your translation of “all that is solid melts into air”?

JS: The German original is “Alles Ständische und Stehende verdampft.” “Stehende” and “Ständische” both come from the verb “to stand,” and is used here as sort of a pun—it refers to both “that which exists” and the society of orders, the old regime world that still existed in Prussia and Austria. “Verdampft” means to “evaporate,” to “go up in smoke.” What Marx was suggesting here is that the power of capitalism—capitalist steam engines (“Dampf” means “steam” in German)—would “evaporate” the society of orders. This would also bring to an end the intellectual world that went along with it: Romanticism, the glorification of the Middle Ages, and religion. Marx’s comment at the end about “man is at last compelled to face, with sober senses, his real conditions of life” is about an age of realism, e.g., literary realism. One of Marx’s friends when he was in exile in Paris was Heinrich Heine, the great early German realist.

Mine is a very different take on the passage. The way it has been interpreted in the 20th century is that capitalism produces many new consumer demands; we have a world which is constantly changing in communications, artistic trends, etc. That’s a 20th century reinterpretation of Marx’s ideas.

SS: One of “Marx’s least successful predictions” from the Communist Manifesto, you note, is that of the imminent end of nations and nationalism: “National distinctiveness and conflicts between nations disappear more and more with the development of the bourgeoisie, with free trade, the world market, the uniformity of industrial production and the relations of life corresponding to them.” As you note, the resurgence of nationalism in pre-1914 Europe belies any straightforward affirmation of what Marx wrote. But as you also note, Marx’s view nevertheless contained an element of truth rooted in Marx’s own experience. Marx had participated with the London Fraternal Democrats and the Brussels Democratic Association, both of which “were based on the cooperation of radicals of different nationalities” (207) and, of course, Marx, whose own perspective was resolutely internationalist, went on to participate in other organizations dedicated to international cooperation. Given this, might we not take Marx’s observation in the Communist Manifesto as indicating, if not straightforward dissolution of nationalism, then its substantial, if subtle, transformation from British patriotism or, later French revolutionary nationalism of the 18th century? In the history of European nationalism, how does the revolution of 1848 serve as a watershed moment? How did Marx and Engels relate to post-1848 nationalisms—particularly Polish and Irish (we’ll get to Marx’s brand of German nationalism later)—and how did this shape their political outlook?

JS: The early advocates of nationalism in the first half of the 19th century tended to envisage antagonisms and military conflicts between different countries as the result of the lusts of monarchs for conquest, glory, and expansion of their domains. They imagined that when states were ruled by nations, by peoples, all of this would come to an end, and nations would spontaneously cooperate with each other. These were the ideas of Giuseppe Mazzini, the leading democrat in 1830s and ’40s Europe, whose organizations Young Italy and Young Europe were designed to be an alliance of different nationalist groups against the existing monarchical order. The Brussels Democratic Association had an absolutely fabulous name: The Democratic Association Having as its Goal the Union and Fraternity of all Peoples. This expresses exactly what nationalists thought. But in 1848, the old regimes are swept away, bringing nationalist governments in power and the first thing that happens as a result is that all these different nationalisms go to war with each other. This is especially the case in the Austrian Empire, with the Germans, the Slavs, the Hungarians, and the Italians all at war with each other. This also happens to some extent in Prussia with the Germans and the Poles, and in the far north of Germany between Germans and Danes. That is, it then became clear that nationalist movements were profoundly antagonistic to one another and that nationalism was a militaristic, bellicose ideology. This was a great disappointment and left many nationalists frustrated.

Marx and Engels developed an instrumental relationship to nationalism. For instance, Marx was a fan of Polish nationalism because it was violently anti-Russian, and he saw the destruction of the Tsarist Empire as a central revolutionary step. Marx’s daughter Jenny, who followed in her father’s political footsteps and became a left-wing journalist in her own right, wrote mostly about her support for Irish nationalism, not communism or the labor movement. Marx and Engels ended up supporting Irish nationalism, because they thought it might ultimately destroy the position of the landowning Anglo-Irish aristocracy, and this, they thought, would be a blow to English capitalism and capitalism worldwide. There were lots of other nationalisms that they didn’t like, like that of the Slavic peoples of Eastern Europe—which tended to be anti-German and pro-Russian. Engels states in Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Germany, which is a sort of post-mortem of the revolutions of 1848, that if we have a revolution in Germany and the Czechs are opposed to it, we’ll just kill all of them—frankly genocidal rhetoric. We see here the way that that these disillusioned nationalities will not in fact spontaneously fraternize, and so it is necessary to view nationalism through its usefulness for revolutionary goals.

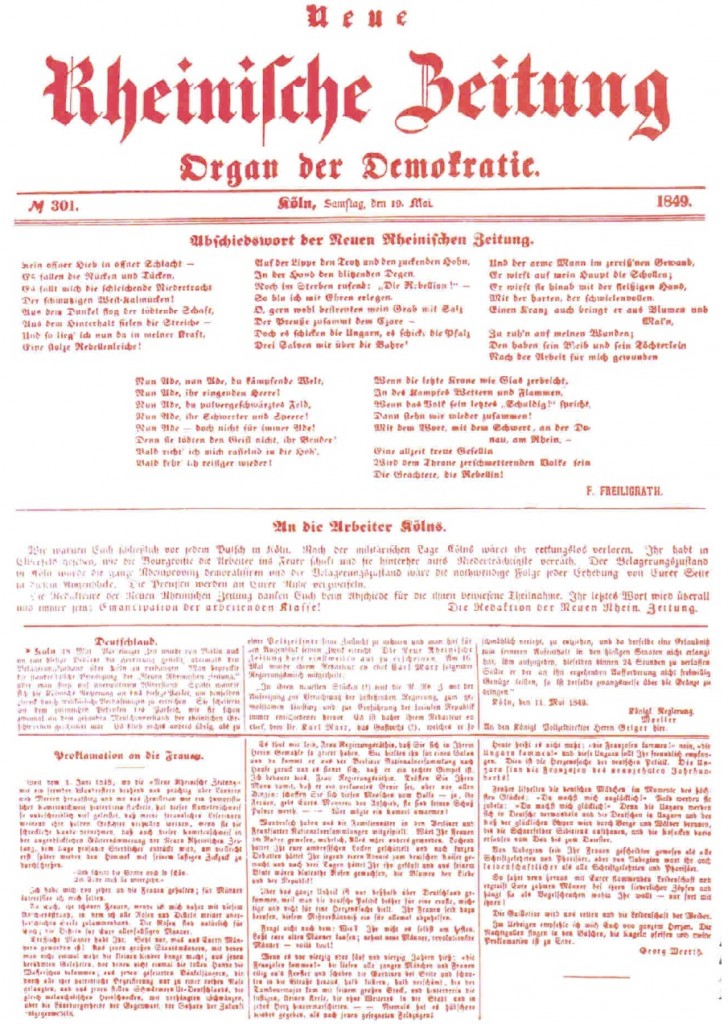

The final issue of the Neue Rheinische Zeitung.

SL: Marx’s stint as an active revolutionary was spent editing the Neue Rheinische Zeitung in Cologne. Reminiscing about the paper in later years, Engels asserted that “war with Russia and the creation of a united German republic were its two main themes” (226).[1] Explain the logic of this and, more generally, the strategic orientation of the paper vis-à-vis other socialists, such as Andreas Gottschalk, whom you described as a “True Socialist, [and] a friend, pupil, and close confidant of [the Young Hegelian philosopher] Moses Hess” (220). What was Marx’s political aim in the revolution of 1848? How did Marx’s political development over the previous half decade or so prepare him for the role he played as editor-in-chief of the New Rhineland News? How did his position evolve over the course of the 1848–49 revolution?

JS: You will remember this idea of the “double recurrence” of the French Revolution, the literal and analogous. Marx had a “double-track” political strategy in 1848 of achieving both of these revolutionary goals at once. His work in Cologne on the New Rhineland News represented the literal, “Jacobin” wing of this strategy that would call for a united German republic, the overthrow of the Prussian monarchy, and revolutionary war with Russia. Marx spent a lot of his time really socking it to the Prussians: making fun of the monarch, the royal family, government officials, tax collectors, and army officers. He stirred up the population against them all. The Prussian officials got angry because Marx was quite good at it. And in the western provinces, the Prussians were widely despised.

The other thing that Marx wanted to do was to organize the workers and to form a nationwide German workers’ association that would prepare for a new revolutionary struggle against the capitalists once this democratic republic was achieved. The first “Jacobin” part worked pretty well, but the workers’ association did not. Marx’s working-class, communist followers were disappointing. They spent a lot of time drinking in the cafes and playing dominoes, rather than trying to organize their fellow workers. In Cologne itself, Gottschalk headed a very large workers’ association—something like every one in three adult males in the city belonged to it—but to be honest it would be fair to describe him and his mentor Moses Hess in contemporary terminology as “airheads”—fabulists who believed that everybody was in favor of communism, and all you had to do was wait a little while in order for communism to emerge on its own. Gottschalk was notorious for refusing to take part in political campaigns. He sabotaged the elections to the German National Assembly by calling the democrats bourgeois frauds and calling on workers not to vote, thereby allowing the Cologne conservatives to dominate the election. He refused to join the republican and anti-Prussian campaigns. He was really screwing everything up, and all the democrats in Cologne were hostile to Gottschalk—Marx was no exception in this respect. When Gottschalk was arrested by the Prussian government in June 1848, Marx and his followers took control of his organization and attempted to use it to support the democrats. But instead the organization itself collapsed, so that Marx found himself, in 1848, pursuing only the Jacobin/democratic half of his political agenda.

In the fall of 1848, a period of revolutionary crises, Marx was busy stirring up efforts to overthrow the Prussian government, and in November these came very close to succeeding. He continued in this vein until the very end of the revolution, until in the spring of 1849 he suddenly changed his mind and began trying to organize the workers again. He broke with the democrats and the movement for German National Unity, and stood aside in the last revolutionary crisis of May 1849. There’s this odd back-and-forth pattern, which would be the same with the International Workingmen’s Association, within which we see the difficulty Marx had in getting both prongs of his “double recurrence” to work simultaneously.

SS: As the U.S. Civil War reached a revolutionary pitch and Polish nationalists rose in revolt against the czar, Marx came to help form the International Workingmen’s Association. Respecting Marx’s involvement in the association and its original aims, you write,

Marx’s plans for the association appeared in his agenda for the First Congress of the IWMA... The items for action included the advocacy of social reform—a shorter workday, limitations on women and children’s labor, the replacement of indirect with direct taxation, an international inquiry into workplace conditions, and the endorsement of producers’ cooperatives and trade unions. There were just two expressly political points, both taken from the arsenal of nineteenth century radicalism: the replacement of standing armies with militias; and “the necessity of annihilating the Muscovite influence in Europe... [via] the reconstitution of Poland on a social and democratic basis.” (358, ellipsis in original)

Starting from this basis, how did the IWMA politically evolve? What developments did it face and what were the central tensions within it? What were the primary aims Marx sought to advance in his struggles over the direction of the First International? How did these evolve into a struggle with the Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin and what was at stake there?

JS: As you can see in the quote, one might think of Marx’s objectives in the IMWA as not involving any specifically revolutionary goals. He saw the IMWA primarily in terms of trade union and workplace-related reform movements. Marx believed that these would ultimately be revolutionary in nature because of his theory of surplus value, according to which capitalists gain their profits by taking part of the product that workers have produced. Marx saw unions as trying to seize some of that surplus value back from the capitalists. He hoped that, if the unions continued this effort with the support of the IMWA, it would tend to reduce capitalist profits and lead to a revolutionary crisis. This was a long-term strategy that would take a while to work out. Marx was supported in these ideas by the English trade unionists that formed the backbone of the IWMA and provided it with most of its meager finances.

The opponents of Marx were revolutionary adherents of secret societies, who saw the IWMA as a means by which to overthrow the existing order in Europe. They were interested above all in this idea of a secret society organization. At first, this was less the case for Bakunin than for the followers of the French revolutionary Louis Auguste Blanqui, who spent the 1830s–1870s plotting revolutions, trying them out, going to jail, being released, and plotting new ones.

There were two things that created tensions in the IWMA. One was its spread, from Northern and Western Europe (where it began), to countries in Southern Europe, where there weren’t really any trade unions, but where the tradition of secret societies was still very active. The second was the Franco–Prussian war of 1870, which disrupted politics all across the European continent. Marx was actually not at first hostile to Bakunin. The two became friends when they met in exile in France in the late 1840s, and Marx was always very impressed with him. When they met again some 15 years later, Marx wrote to Engels saying that Bakunin was one of the few people who had moved forward in the interval rather than backwards. Bakunin was an enormous fan of secret societies, and became involved with some very dubious ones like that of Sergey Nechayev, who was famously depicted in Dostoevsky’s The Possessed. He therefore found himself increasingly in opposition to Marx. This eventually led to a break between the two, and a struggle for control of the IWMA. As part of this struggle, Marx decided that the IWMA had to endorse the idea of workers’ political parties. At the time, very few workers’ political parties existed. There were two competing ones in Germany at the time, but Marx trusted neither entirely. This led to a ferocious struggle between Marx and his followers, and frankly every other element in the IWMA. In the 1872 Hague conference, Marx’s followers were victorious and they expelled Bakunin. They then moved the headquarters of the IWMA to New York, basically with the intention of destroying the organization; Marx realized that plans for revolution probably had to be shelved after the repression of the Paris Commune. Just as Marx took control of the organization, he chose to bring it to an end.

SL: Why was Marx concerned to maintain the IWMA as an open, democratic political activity? A quarter century before, Marx and Engels had fought to publicize the activities of the Communist League, though it is true that, after the reverses of 1849, the Communist League took on a secret, underground form. Still, is it fair to say that the struggles in the IWMA repeat his struggles in 1847 for an open form of politics and publication?

JS: I think so. The Communist League did adopt a clandestine form after 1849, but that’s because open political activity was essentially impossible in an age of revolutionary repression. Marx was always a proponent of open politics. He was a newspaper editor—this was always one of his chief forms of political activism. Marx was suspicious of secret societies and believed wholeheartedly in open politics. One of the ironies of his struggles against Bakunin was that Marx was convinced Bakunin was trying to undermine the IWMA by smuggling in his followers in order to form a secret society within the IWMA itself. This was actually not the case, and it was ironically one of Marx’s allies who was proposing this idea, the veteran German revolutionary Johann Philipp Becker. Marx flew off the handle at Becker’s suggestions, and thought he was being manipulated by Bakunin.

SS: Two of Marx and Engels’s key associates in the German workers movement were Ferdinand Lassalle and Wilhelm Liebknecht. Eventually, it was Liebknecht, who opposed Lassalle’s coziness with Bismarck, who came to enjoy Marx and Engels’s support. One crucial division between the two, and what eventually divided Lassalle from Marx as well, was again the question of nationalism. As veterans of 1848, they all supported in some sense the cause of Germany, but Marx articulated this as an anti-Prussian demand for a German republic. Yet, in the face of eventual German unification enforced by Prussia, Marx and Liebknecht were forced to make something of it. This meant coming to some sort of terms with the followers of Lassalle. What were the fundamental underlying tensions expressed by Liebknecht’s opposition to the Lassalleans and to what extent were these overcome?

JS: There were three issues here. One was the question of the nature of a united German nation-state. Would it be a Grossdeutsch one that included the ethnic Germans of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, or would it be a Kleindeutsch one, without those Germans, and so exclusively dominated by Prussia? Marx was always a Grossdeutscher and, certainly, Liebknecht was a follower of Marx on this point, while Lassalle was strongly opposed. But the issue was ultimately decided by war: The Prussians trounced the Austrians in 1866, therefore Bismarck’s state would be a Prussian–dominated Kleindeutsch state. Marx was unhappy with this, but he understood that he had to come to terms with it.

The second issue was whether the German nation-state would be a democratic republic or not. Liebknecht, as a veteran of the revolution of 1848, was a strong adherent of the idea of a democratic republic. Lassalle was too, though he flirted with the idea of a constitutional monarchy, and had conspiratorial meetings with Bismarck. This tension too was decided by history. The united German nation‑state persecuted both the followers of Liebknecht and Lassalle equally, and the followers of Lassalle increasingly became opponents of the existing monarchical order.

The third issue, and this was the really tricky one, was the question of relations between the labor movement and liberal–progressive parties in the German government. Lassalle and his followers clearly despised the liberals and made deals with the conservatives, while Liebknecht and his followers were willing to make deals with at least those democrats that shunned the conservatives. This was an issue that, even after the two wings of the labor movement united at the Gotha Congress of 1875, remained alive in the German socialist party. There were some who felt that opposing liberalism was their primary aim, even if it meant collaborating with conservative authorities. Others felt that opposing the conservative authorities should be the primary aim, even if that meant collaborating with the liberals. |P

Transcribed by Tom Willis

[1]. See Friedrich Engels, “Marx and the Neue Rheinische Zeitung (1848-49)” available at <ahref="http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1884/03/13.htm">http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1884/03/13.htm. In that 1884 piece, Engels observes, “The political program of the Neue Rheinische Zeitung consisted of two main points: A single, indivisible, democratic German republic and war with Russia, including the restoration of Poland.”