Black politics in the age of Obama

Cedric Johnson and Mel Rothenberg

Platypus Review 57 | June 2013

On May 6, 2013, the Platypus Affiliated Society hosted a conversation on “Black Politics in the Age of Obama” at the University of Chicago. The speakers included Cedric Johnson, the author of Revolutionaries to Race Leaders: Black Power and the Making of African American Politics (2007) and The Neoliberal Deluge: Hurricane Katrina, Late Capitalism, and the Remaking of New Orleans (2011); and Mel Rothenberg, a veteran of the Sojourner Truth Organization and coauthor of The Myth of Capitalism Reborn: A Marxist Critique of Theories of Capitalist Restoration in the USSR (1980). Michael Dawson, author of the forthcoming book, Blacks In and Out of the Left, was unable to attend due to an emergency. The event was moderated on behalf of the Platypus Affiliated Society by Spencer A. Leonard. What follows is an edited transcript of the conversation. Complete audio of the event can be found online by clicking the above link.

Cedric Johnson: I want to demystify the Obama phenomenon, which dates back much further than the 2004 DNC, as it has unfolded over the past decade. I also want to demystify the notion of “black politics” generally.

I am not disappointed with Obama, because being disappointed would mean I had expectations that had not been realized. I certainly disagree with Obama, but he has done just about everything I expected him to do with respect to domestic policy, questions of inequality, or geopolitics. He has been fairly consistent.

The problem with the Obama phenomenon is that too many people got caught in the rhetoric of “change.” As a political slogan it was perfect: No matter where you were, you could find something you could connect with. This operated on at least three different registers. On one level, it simply meant a change to another party’s leadership. For some, simply turning the page on the Bush years counted as change. At another level, there was what might be called the Jackie Robinson effect: There were those who wanted to see Obama break the barrier and become the first black president. Finally, and this was the most dangerous, many believed that Obama was going to deliver some substantive revitalization of liberalism within the United States. The idea was that he would be the second coming of FDR. People have made the same argument more recently. Michael Eric Dyson made this case last year on Democracy Now!, in fact, urging support for Obama’s reelection bid. One or another of these arguments proved convincing for many who ought to have known better—not just liberals, but people who consider themselves Marxists or radical leftists.

One reason Obama emerged as such a powerful figure during the 2008 election season has to do with the context of demobilization, particularly within black life. There was not a large and vibrant enough political movement on the ground, a movement that could connect to people’s realities in terms of their work lives, their everyday lives, and the character of life within neighborhoods. This created a void that was easily filled by a politics of recognition and the symbolism of the Obama campaign. But if we look closely at Obama’s politics, if we go back to that 2004 DNC address, when it comes to domestic politics he has always been clear: a minimized role for government. He wanted to do away with the benevolent role of the state that we had become accustomed to by way of the New Deal and Great Society. He even endorsed the Cosby tirade against the urban black poor. More than once before he announced his candidacy, and many times since—most recently in the address he delivered in February at the Hyde Park Academy—Obama has not emphasized the economy, but parental responsibility and behavior modification as a way of addressing the routinized violence in American cities. What Obama has done skillfully, particularly in his primary race against Clinton, is combine the liberal, public relation society of the new Democrats with neoliberal politics.

Most other black folk do not want to deal with these issues. For them, engaging in criticism of Obama is seen as airing dirty laundry, or as part of some insidious plot to sabotage him. So what we have also seen, in his rise to the presidency, is the wholesale decline of critical engagement within black publics. It is very difficult to find a spot where you can openly criticize Obama and have it heard—actually heard, understood, and appreciated in some meaningful way.

Part of the problem, of course, rests in how we think about black politics. I want to distinguish black political life—a broad category stretching back across multiple decades, even centuries, in reference to black people engaging in various forms of politics, whether slave rebellions or the push for desegregation of the South—from black ethnic politics as a peculiar phenomenon that develops during the 20th century, particularity after the 1960s. When we talk about black ethnic politics, we are talking about a form of politics that is, first of all, predicated on the notion of ethnic group incorporation. Too many people talk about African-American political life and African Americans as a group, as if they constitute a corporate political entity, as if there are clearly defined interests widely shared by all African Americans. The way political scientists do this is to engage in public research—you find some issue for which there is 70% support, and from there make the leap that this constitutes black interests. This is deeply problematic, in my estimation, as it says very little about what black interests look like within real time and space.

Another part of the problem is that we are still burdened in part by some of the arguments made during the 1960s, which were powerfully influential among black power radicals. The result is an epistemology from a racial standpoint, which assumes that because of the common experience of racism within the United States, African Americans attain consciousness of the society distinct from whites, and ultimately their common interests come out of that. Although false, many on the left continue implicitly or explicitly to perpetuate this notion.

Those who dare to criticize Obama openly, in public, are deemed race traitors—people like Glynn Ford, even Tavis Smiley and Cornel West, and certainly Adolph Reed, Jr., and others. Usually the discussion rolls back to the question, “How can we hold Obama more accountable? How do we come up with the black agenda everyone can agree on, bring it to Obama, and have him adopt at least some elements?” However, if we begin to think in a critical way about black political life, rather than being mired in black ethnic politics, I think we can end up with different ways of engaging these questions not only as academics, but also politically.

I want to conclude my opening remarks by referencing a comment made by Harold Cruse, a former Communist intellectual, in a seminal 1962 essay called “Revolutionary Nationalism and the Afro-American.” In it Cruse offered a criticism of Herbert Aptheker, arguing that one of his problems with Aptheker, and other white leftists, is that they can “only see Negroes at the barricades.” That is, they see blacks only as some sort of rebellious force in American society. For Cruse, such a view betrayed little understanding of the internal class politics among African Americans.[1] While Cruse points out the class difference, he ultimately carves out a privileged place for black elites. Whenever this criticism is made you always get the response that you shouldn’t put so much emphasis on these black elites and their participation in the local power bloc within black communities. You often hear that, if anything, they are junior partners. You might even hear people argue that black elites are dupes who simply don’t know better. But that is tacitly racist: Even when black people are in power, they can’t have power, and they can’t be held accountable for the things that they do. On the contrary, particularly right now in the period of neoliberal “roll-back and roll-out,” there is a unique role that black elites play in many cities. They play an important legitimating function—one that whites cannot play. Oftentimes they serve to deflect criticism from the very communities that might oppose these neoliberal policies as they’re being developed.

Mel Rothenberg: I am delighted to participate in this forum with Cedric. I also want to thank Platypus for organizing and inviting me. They do a real service on campus in organizing panels like this. I agree with Cedric’s analysis of Obama. I’m not sure I agree with him about black elites, and I expect he’ll disagree with me on some things. I don’t pretend to compete with Cedric as a scholar. I’m an activist, and my role here is to be the veteran leftist trying to extract from about 60 years of social activism some lessons that bear on the important issues at hand.

After superficial involvement in civil rights activity as a graduate student at Berkeley in the late 1950s, I got involved with the Chicago-area Friends of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in the early 1960s. It was a racially mixed group, primarily of young activists but with a core of experienced leaders. Despite its rather clumsy name, Chicago SNCC became a major force in the blossoming Chicago Civil Rights Movement of the early 1960s, leading a massive public school walkout and strike that succeeded in removing a racist school superintendent. As a result an all-white administration and a highly segregated school system were opened to input from the African-American community. It was one of the more successful struggles of the period.

I had joined Chicago SNCC out of a liberal opposition to racism and racial discrimination, but my years in the organization became a defining experience for deepening my politics and future political activism. Through SNCC, which combined active organizing with many heated debates, I came to understand that the black struggle in the U.S., which went back over 300 years to colonial times, was very complex. It was a shifting struggle against caste, national, and class oppression. I never understood why we had to decide which of these it was: The black liberation movement was all of these things. The struggle against caste, the struggle against national oppression, and the struggle against class were interrelated. At different times different features became predominant, but there’s no one characterization adequate to a struggle this long and this complex.

I became convinced that the struggle for black emancipation was central to any progressive transformation of the U.S. social order. To paraphrase Marx, the emancipation of black labor was key to the emancipation of the American working class. I also became convinced of the converse: A black movement, to be successful, must be animated by a vision of human emancipation. A black movement that narrowed its sights exclusively to the interests of African Americans would be isolated and defeated.

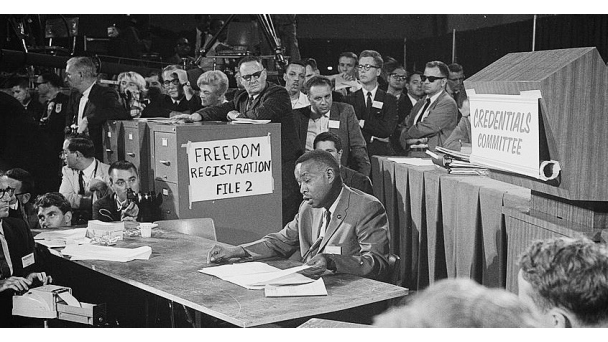

Those are generalities. Now I want to look at a concrete historical moment in light of the themes I’ve raised. In 1964, at the height of Civil Rights Movement, Fanny Lou Hamer and other leading civil rights activists organized the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). They sought to challenge the racist leadership of the Mississippi Democratic Party, which had excluded, both by law and through extra-legal violence, any participation, including voting, of Mississippi blacks in politics. Excluded from the official primary choice of delegates to the Democratic National Convention scheduled for the fall of 1964, MFDP organized its own primary process. They selected a delegation to the convention to challenge the seating of the lily-white racist delegates chosen by the official Mississippi Democratic Party.

Aaron Henry, leader of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, before the Credentials Committee of the 1964 Democratic National Convention.

This was at the height of the Civil Rights Movement. The massive 1963 March on Washington had driven home the 1963 federal civil rights bill, outlawing much legally enforced discrimination. The 1964 civil rights bill, then on the agenda, would prohibit the poll tax and other barriers to black voting. The whole Jim Crow system of legal enforcement of the caste system, which deprived blacks of the elementary political and social rights automatically enjoyed by whites, was crumbling. Within the next few years it would be wiped out. In this context, the black movement was turning to confront national and class oppression beyond discrimination against individuals. This raised issues of enfranchising of the community and the freeing of black workers who were universally relegated to the lower layers of the working class and to the reserve army of labor. At its sharpest this raised the issue of political power for the community, an empowerment that ultimately threatened the existing class and property relationships.

The challenge of the MFDP was then a move for community political power. It occasioned a crisis in the national Democratic Party. The party leadership was extremely concerned with the long-term implications, not just in the 1964 elections. Everyone knew that President Johnson would be nominated and, riding a wave of popular approval aided enormously by his success in passing civil rights legislation, would be reelected. What the Democratic leadership was concerned with was the impact the MFDP challenge would have on their electoral hegemony in the south, overseen by white racist party organizations. Lyndon Johnson was explicit about this.

The decision of the Democratic leadership was to try and juggle both balls. On the one hand, the Democratic Party would embrace—it really had no choice—the end of Jim Crow. On the other hand, it would keep the southern racist electoral apparatus in tact, making some mild cosmetic changes to accommodate the times. The decision was to prove disastrous for the Democrats, as well as for the black movement. The Democrats managed to lose political hegemony in the south, which they have never recovered to this day. At the same time, they set themselves in opposition to, and effectively frustrated, the development of a black movement that could have led the coalition to the next level of struggle.

Walter Reuther, head of the United Auto Workers union (UAW)—probably the leading progressive trade union figure, and a major figure in the Democratic Party—was chosen by the Democratic Party leadership to negotiate with the MFDP’s demand that they be seated instead of the racists.

The UAW was the leading industrial union then. I myself had worked in the Wayne Mercury Auto plant in the 1950s, which was not an unusual assembly plant. Among the thousands of workers, about a third were black, dating from World War II; another third were white, including the majority of skilled workers and those who had been there the longest (mainly of Eastern European background); and the final third were the most recent workers, white southerners from rural and small-town backgrounds who tended to work part of the year, during the busy season, and returned to the south during the slow periods. Auto assembly tended to be seasonal at that time.

The politics in the plant were very complex, yet revealing. The ruling union caucus followed Reuther. This caucus was based on the older white workers, but with a significant following among black workers. The opposition caucus, which was strong and periodically controlled the elected plant union, was a mixed bag in which leftists dominated. Some of these were members of the Communist Party, but also included were a significant number of black workers. The newly arrived white southerners were less active overall, but some formed the basis of a small but visible Klan-affiliated racist white caucus.

The point I want to make is that there was then a significant mass of civil rights supporters among the union members, including in Reuther’s caucus. Reuther himself had been a visible civil rights advocate and the UAW had good relations with the mainline civil rights organizations, such as the NAACP. It was also supportive of the more militant sectors led by King and even provided discreet financial support to the most radical wing led by SNCC. This is why Reuther was chosen to negotiate with the MFDP. He had credibility with them.

What Reuther and the Democratic leadership ended up offering the MFDP was to add a couple of their leaders to the official delegation with the stipulation that the MFDP would abide by the majority decisions of the racist delegation on what issues to raise and what motions to support. This so-called compromise was obviously unacceptable. In the end the racist delegation walked out, offended that they were asked to mingle with MFDP people, but the MFDP delegation was not seated and organized a brief sit-in to protest. It also left the convention.

What were the consequences of this? The black movement learned that when it came to issues of community power and, more broadly, issues of national oppression, their white liberal allies, and in particular those involved in labor politics, would abandon them. This is the lesson they, and SNCC, which I was in at the time, drew from this. The betrayal by labor was particularly damaging because effectively raising class issues, fundamental to black emancipation, was only possible with the active participation of a substantial section of white workers. For this, the active involvement of at least a powerful section of the trade unions was required. The rejection of the MFDP at the 1964 Democratic Convention by even the most progressive section of labor convinced the most advanced elements of the black movement that this coalition would not consolidate.

Within the year, the slogan of “Black Power,” which previously had been raised by only the nationalist fringe of the black movement, had become the dominant battle cry of a much broader militant layer. Stokely Carmichael, who became head of SNCC in 1966, took this slogan up in 1965. He also wrote with Charles Hamilton the most influential argument for Black Power, bringing it into mass action in Birmingham and Watts as the Civil Rights Movement moved north.

One cannot really fault this turn by the militant black leadership. Given the black upsurge generated by the earlier period of the civil rights activism and the rejection of opposition to national oppression by their white liberal supporters, and in particular labor, they had nowhere else to go. If you have to fight the battle against national oppression by yourself, without significant white allies, you have to do it under a banner that can unite the vast majority of blacks. The tragedy, however, is that by narrowing the struggle in this way to being a minority nationality struggle, it became much more difficult to win. In fact, the struggle presumed that the ruling elite—the ruling white elite—despite the vast economic and military resources at their disposal, were too divided and weak, presumably due to international anti-imperialist movements, to sustain their system of white supremacy. The experience of the last 40 years has not born this out.

These issues consumed the Civil Rights Movement. Malcolm X, trying to negotiate the terrain between narrow nationalism and a broader anti-imperialist perspective, was murdered by hardcore nationalists. Martin Luther King, committed to a broad coalition, linked up with the developing anti-war movement. Attempting to maintain unity between the older liberal civil rights forces and an emerging youth-based and multi-racial anti-imperialist movement, in the late 1960s he turned to labor and class-based struggles. This was a promising development, cut short by his assassination by racists. The Civil Rights movement spawned many significant social movements in the decades that followed, but as a black-led broad political movement that presented a fundamental challenge to the existing social order, it was dead by 1970.

Of course, the Civil Rights Movement was not a total failure. In its first phase, up to 1964, when its focus was fighting caste oppression—the system of Jim Crow laws and discriminatory practices—it held together and was largely successful. Its major social impact was to promote the creation of a new black middle class integrated into the mainstream of U.S. economic and social life. The three-generation rise of Michelle Obama’s family is a striking example of this quite significant achievement. Still, though African Americans have benefited from the demise of Jim Crow, the fundamental national and class oppression that weighed on the majority of blacks 50 years ago has not disappeared. In certain basic respects—unemployment, incarceration, lack of community empowerment—it has arguably worsened.

The failures of the movement of the 1950s and ’60s had an equally profound impact on subsequent American history. There had been a white racist backlash since the Supreme Court banned legal school segregation in 1954, and this continued throughout the battles of the next few decades, up to and including the 1974 Boston school boycott organized against the busing of black students to white schools. This backlash was organized politically by George Wallace in his 1968 run for the White House, and then officially cultivated by the Republican Party in their “Southern strategy” first articulated by Nixon in 1968 and perfected by Ronald Reagan in his successful presidential campaign of 1980. They made Lyndon Johnson’s worst fears come true by creating a white multi-class racist political bloc that has guaranteed the national electoral hegemony of the Republican Party and has been a bulwark of reactionary politics for the last 40 years.

With the triumph of neoliberalism over this same period, the capacity of the trade unions to confront the wave of deindustrialization has disintegrated in recent years. The steady decline in the life conditions of workers, both black and white, and the consequent implosion of the trade unions unable to defend against this decline, is due in part to the failure of these unions to make common cause with the black movement of the 1960s. What was at stake was not only the future of black workers but also the soul of white workers. The defection of large sections of the white working class to Ronald Reagan and his right wing movement was not inevitable. It became so when labor leaders, claiming to represent working class interests, declared war on black militancy and its demands. If Walter Reuther had thrown in his forces behind the MFDP, King and his allies would have certainly had to follow. This would have split the Democratic Party. Lyndon Johnson, at the end of the day, might have had to go along with the anti-racist forces, we might have avoided the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights Movement would have been reinvigorated as a coalition between blacks and labor, and U.S. history would have been altered. Of course none of this happened.

I will leave the conclusions about current black politics that one can draw from this to the discussion. I just want to add the following remark. Since 2007 we have entered a period of economic crisis across the entire capitalist world. The condition is analogous more to the situation of the 1930s than to the period of relative prosperity of the 1950s and 1960s, which were at least prosperous for white people. For a large majority of blacks the conditions today are pretty close to the depression conditions of the 1930s, although things are not yet that dire for white folks. The new factor is millions of immigrant workers from Latin America, who suffer in conditions similar to blacks at the moment. If a coalition of working-class blacks and Latinos can be forged—and this is a big if—then the basis of a major explosion of labor politics will be established.

If a black leadership develops with the capacity to fuse the community aspirations of African Americans with the class demands of such a labor explosion, then there will be a basis for a black-led movement that can change America’s future.

Responses

CJ: Two things differ markedly about black politics during the 1950s and 1960s compared to now. The first is Jim Crow segregation in the south and beyond the south. The other circumstance was the de facto segregation in the north, in terms of the racial ghetto, which was different from what people mean by that term now. In the 1940s and ’50s, if you drove around Hyde Park and the surrounding area, you would find neighborhoods that were class diverse but racially homogeneous. That phenomenon gives way to major changes from the 1960s onwards, as we see black suburbs pop up in different parts of the country. That is significant. Indeed, it’s an accomplishment, as is the expansion of the black middle class. Yet, it is this very accomplishment that ultimately erodes the use of some of those older racial justice arguments in our contemporary period.

Consider Michelle Alexander’s recent book The New Jim Crow—which is all the rage right now, with even churches studying it in groups. Of course, I am glad people are concerned about the rise of the prison state. At the same time it’s not helpful, as I think even Alexander herself concedes at times, to talk about the rise of the prison state as a new form of Jim Crow. That is not what we are facing. We are not even facing mass incarceration as such. Rather, I agree more with Loïc Wacquant: This phenomenon is hyper-, not mass, incarceration. It is not the case that everybody in this room or even all black people will spend their lives or parts of their lives in prison. Rather, when we look at this up close, and this is where historical materialism can be helpful, we are talking about specific neighborhoods targeted by police and these areas are where the majority of prisoners at a penitentiary like Statesville hail from. This is not wholesale incarceration. That, for me, erodes the usefulness of a strict racial justice framework. I also don’t want to give the impression that we should focus solely on class, criticize black political elites, and toss out a discussion of race. Rather, we need to think about class politics and how they manifest themselves in a racial idiom.

MR: When you criticize black elites and say that some people don’t even hold them responsible when they have power, there are two notions of power that need to be borne in mind. One is the power of an individual having some influence and links to important people. The other is the power of a class or a community as a collective force behind you. My own sense is that these black elite leaders lack power in this second sense. People like Obama have a middle-class black constituency that is very much behind them, but a lot of these so-called movers and shakers in Chicago don’t have real community support behind them. They have connections, sources of money, and so on, but they don’t really have power in the sense being able to provide leadership. They can provide no real leadership because they’re basically lapdogs of more powerful people who are controlling them.

Q & A

Would you address the divergence on the Left between a nationalist approach and an integrationist approach? Traditionally these can be thought of in terms of organization—for instance, the Black Panthers’ organizing separately from white activists in the early 1970s. But their difference can also be thought of in terms of the final goal, as with the black belt nation thesis, which sought some kind of national independence and autonomy for black people, as opposed to the revolutionary equality that was imagined by others on the Left. What are your touchstones with respect to this question? What are your touchstones from the history of Marxism?

CJ: This notion of nationalism versus integrationism is anachronistic. That way of talking about African-American political life is dated and no longer useful. If we want to come up with some categories for thinking about African-American political life that might be helpful I prefer Preston Smith’s use of “racial democracy” and “social democracy.” On the one hand, you have struggles that are pitched towards the protection of constitutional rights, particularly within this environment in which the gains of the 1960s have been under assault. That co-exists with racial-uplift and self-help politics—easily!

Some of the divisions that we saw historically have been reconciled. For instance, there was a recent symposium featuring Boyce Watkins and the Minister Louis Farrakhan, and I think the title was “Wealth, Education, Family, and Community.” So there you have it, right? The old Black Nationalist arguments and the liberal integrationists have been reconciled.

What is missing, and this is where we need much more public argument, has to do with social democracy. So if the racial democracy view holds that liberal democracy is great, but it is racist, and we need more black people to have access to it—that is the old liberal integrationist argument—that is not as radical as the view of social democracy, which says that whether it is public housing or support from the state in moments of economic downturns, those things should be guaranteed to all people regardless of color. That is a much more expansive argument, and it has been made over and over again throughout history and has been widely embraced by all sorts of folks within the African-American community.

The racial justice approach seems strong in the abstract, as, for instance, when we talk about the likelihood of a black man getting stopped by the cops or how tough it is for a black man to find a cab in New York. But such abstractions lose their luster when you get into concrete politics. Let me give you one quick example: Some of you all may have noticed, a couple weeks back, Ed Gardner was trying to make a pitch to Rahm Emmanuel for 50 percent, I think, of the contracts coming out of the school closures and demolitions, as well as the rehabs and new buildings.[2] That fits with racial democracy—blacks should have access to contracting just as anyone else, especially if we constitute a disproportionate number of folks within the schools. The problem, however, is that this approach suspends critical analysis: Why try to get a piece of the action instead of contesting this project that could disrupt the lives of thousands of kids within the Chicago Public Schools in ways that we can’t even predict? So I think those are two different kinds of politics operating among African Americans, the one that says “Cut us in. Give us a chance to participate in the same way,” and another approach which contests the contemporary arrangement and calls for something that is more expansive, redistributive, and democratic.

MR: Historically there has always been an element of national oppression involved in the oppression of black people in the United States. They have been oppressed as a nationality—as a people, not just individually or as a caste. The push back to that is to demand community power.

Unfortunately, sometimes the struggle against national oppression takes the perspective of a kind of utopian separatism. That is perhaps an inevitable sentiment, but it is ultimately a futile one. Because in a society this complicated and this integrated, economically and socially, separate communities in that sense are inconceivable. It would only make sense if society were actually falling apart. And this was, in fact, a lot of the analysis of the Black Nationalists in the 1960s and 1970s. Many among them assumed that white society was falling apart, it was collapsing, in any case, it was going to chaos, and African Americans have to save themselves by building their own society, building barriers against the craziness and the corruption and the rot outside. But that analysis was wrong. The white society, the dominant society, may be in a lot of trouble. There may be a lot of injustice. But it is not collapsing. It’s not going to disappear in the next period, and therefore, strict separatism doesn’t make any sense. On the other hand, you have to understand that the notion of community power and community control is genuine and remains crucial to the black struggle.

Marxism is a framework, both my framework and Cedric’s framework. It’s not a view that leads to position, as such, since it is not a politics. Various politics can fit within that framework and there’s always a lot to dispute. In the political sense I am a pragmatist. If politics just doesn’t accomplish real goals then it might be fine in theory, but it’s useless, really. For me Marxism has always been a framework within which to analyze things. Of course, that framework leads me to think of the working class as a prime moving force in history and the prime force for social change under capitalism. I still believe that. There is no other force capable of transforming capitalism. But, beyond that, the particular politics of Marxism depend a great deal on the circumstances, the conjuncture, the country you are in, the circumstances you are in, and so on.

My question concerns community oppression and community politics or community empowerment and the connection to racial/ethnic politics. You both talked about the transformation of these politics with respect to the Democratic Party from the period leading up to the Civil Rights Movement and after. Has the Democratic Party operated as a vehicle for community politics in the United States in a way that the Republican Party has not?

MR: As to the Democratic Party, the politics is complicated by the fact that the Republican Party has organized a racist, white multi-class racial bloc that anchors its popular appeal and hegemony. Even though Clinton, Carter, and Obama were elected as Presidents in the last 40 years, the Republicans really have a national electoral hegemony. They control things and set the agenda even when the Democrats hold the presidency. They set the agenda because they have organized this bloc from which the Democrats are excluded by definition. The Democrats have their own political machine—we can see that in Chicago—their own combines, which operate very effectively at the city level and certain state levels. But if you want to oppose the white racial block you have to do it within the Democratic Party. The strategy of taking over or splitting the Democratic Party from the left, however, has no real basis in society. Still, as a way of fighting the most racist and right wing elements it does have some logic. What are black communities going to do, run as Republicans? I mean, if you are going to have any kind of representation whatsoever, in Congress or in the legislature, and if it is going to be at all progressive and anti-racist, it is going to be Democrat. That is the fact we are dealing with. The dilemma is that the Democratic Part is not a way for the Left or for the black movement to advance any deep agenda. But in the short run, as a defensive maneuver to fight the racists, it might very well be a tool, at least locally, that you have to use.

CJ: I want to introduce the question of talking about class politics in a racial idiom. This is something I take from Preston Smith’s work, Racial Democracy and the Black Metropolis. It is really a straightforward proposition, as I see it, though it is an approach to black politics that has been lost, both popularly and in academia. If you go back and read Jim Crow-era social scientists—Abram Harris, W. E. B. Du Bois, Ralph Bunche, even E. Franklin Frazier and Carter G. Woodson—all of them offer an analysis of black politics that looks at it in its full expanse. They address how class manifests itself among African-Americans.

One thing that happens within such discussions, particularly in our own time, is that we conflate race and class. There is a tendency to use race as the symbolic language of class. It used to drive me crazy when I taught at a small liberal arts college where many students automatically equated “black” with “poor.” They saw black people as being synonymous with poverty and they had no understanding of African-American life beyond that kind of image they got from pop culture. So, I tried to talk to them about Bronzeville, or about the fact that even in the small community that I grew up in in the 1970s and 1980s in Louisiana, we had black banks, black doctors, and black lawyers. The idea that there is an integral aspect of African-American life was something new to them. The task for us, and this is what I was trying to lay out before, is to talk about those differences.

Race is not the same as class. When we talk about class we talk about particular roles that people play, their specific relationship to production in our society. Race has its origins in slavery and imperialist expansion. But, ultimately, when we look at contemporary African-American politics, we need to address how communities are organized and how particular kinds of politics and sets of interests emerge. This flows from what I said at the very beginning about the disappearance of critical public engagement among African-Americans: I grew up along the Interstate 10 corridor—most of my family was in either Louisiana, Houston, or Mobile. Most of the people whom I learned from as a kid had grown up under Jim Crow. The teachers I had as far as high school were largely people who had taught at the old Jim Crow high schools in the area. They talked about class. They didn’t talk about it in the ways that academics talk about it. They had their own vocabularies for the differences of opinion and interests among African-Americans. And the discussions were often quite candid. Some of that has since disappeared. You hear it every now and again in, for example, the use of the term ”Uncle Tom,” which was one that I heard constantly as a kid. I recall adult conversations in the other room: They were talking about local politics, they were talking about people they knew personally, and they weren’t afraid to call these people out when their politics were out of step with the broader community of mostly working class African Americans. That kind of internal criticism has evaporated by and large. So why do we no longer have those forms of public engagement, analysis of everyday forms? Why have they evaporated?

MR: The discussion of class has not only dried up in the African-American community, but in the white community as well, including among white workers. There is a notion that everybody is now middle class. If you have a decent job you’re now middle class, not working class. So an entire terminology has disappeared. Or, if it hasn’t disappeared, it has deteriorated because of the absence of a left in this country. One of the functions of the Left, according to Marx, is to raise these issues. We haven’t had an effective Left for some time, so that this kind of talk, these kinds of class discussions, have tended to disappear from public view and even from private conversations. I remember at the time of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s and of the League of Black Revolutionary Workers in Detroit in the 1970s, when there was a surge in working class militancy, especially amongst black workers but also amongst whites, this terminology of class did arise. It was the way people talked, even right-wingers. It became part of the conversation, the hegemonic vernacular, if you will. But it has tended to disappear in our society.

It would seem that politics thought of in terms of the “black community” and ”white community” points to earlier failures of what was termed the “revolutionary integrationist” project. It seems that the radicalism of that vision—that black people wouldn’t just be incorporated into a society that didn’t otherwise change, but that integration necessitate wider social transformation—has been lost. Similarly lost is the recognition of the crisis of liberalism that was expressed by Jim Crow, a crisis that was not itself overcome with the dismantling of Jim Crow. Is this language of black and white communities the best that we can think of now? Are we content to naturalize that there is a black community and that it has its own politics? Where does this leave the question of the political leadership of society? Doesn’t an exclusive preoccupation with the black community actually threaten to limit our political horizon?

Hasn’t the project of social democracy in the United States always had racism woven into it, from the New Deal to the Great Society? This seems to complicate Preston Smith’s contrast between racial democracy versus social democracy. The critique of racism attained some of its most radical forms in variants of revolutionary Black Nationalism. I am curious about that strain of black politics and its place on the Left, especially in light of the Obama administration’s designation of Assata Shakur, who was considered a central figure for part of the Black Liberation Army during the 1970s and 1980s, as the most wanted fugitive on the FBI’s list. Obviously, there are various political considerations involved in that decision, but in some ways it represents a symbolic culmination of COINTELPRO. Can we not say that the military defeat of revolutionary nationalist politics has opened up the space for, and legitimacy of, the more integrationist politics that Obama represents? Where do we understand the place of Black Nationalism, particularly that strain of it engaged with Marxism?

When I first read The Souls of Black Folk, I was impressed with the way Du Bois spoke with such high praise of the use of military force in the South, of Reconstruction as a military project imposed upon the South. If Reconstruction was the height of black politics in the history of the United States, if it was the most progressive time in the history of this country, what would it mean for us to actually have a politics that worked at that level, with elections forcing the key political issues of the day, as opposed to what we have now, where the president is just a symbolic figure? Mel has pointed out that he thinks the major task is the question of jobs, and it certainly was the major issue in the last election, if it isn’t the major issue in all elections. What is the significance of the fact that the black community is used as a surplus labor force alongside immigrant labor?

MR: Yes, community politics can be narrow and provincial. On the other hand, when you have oppressed communities who have no power, you are going to have resistance, you are going to have community-based politics. This just seems to be a natural social law. You cannot be dismissive towards those local political struggles just because they are local.

Generally, one aspect that must be understood is that the ideas of the revolutionary Black Nationalists influenced the white left tremendously in this country. They were very important in the New Communist Movement and in the white left. The New Communist Movement has vanished in a way that the debates of those times, which were occasioned by these revolutionary Black Nationalists’ ideas, has been forgotten and lost, and that is too bad, because it was a very important and fundamental debate. The African-American struggle is—at least one aspect of it is—national. Blacks are a nationally oppressed group, and revolutionary Black Nationalism emerges out of that aspect of the reality of the struggle, as an attempt to integrate responses to the national oppression and the class oppression. Some such integration, in terms of theory and praxis, is crucial if you’re interested in building any kind of revolutionary movement.

Du Bois’s book on Black Reconstruction is to me the high point of Marxist analysis of that period. But I am not sure the issue of violence is central. The issue there was of democratic self-rule, basically, where the planters had mobilized a force of violence to crush democratic self-rule and they fought back. The controversy is whether they could have made it or what allies they needed to sustain the Reconstruction project and avoid defeat. There is no doubt that if they were going to do that they would have to employ armed struggle, because they were under armed attack.

CJ: I actually try to refrain from using the categories black community/white community, partially because when we encounter them within political rhetoric, or even in earlier historical debates, what they refer to is a constituency that someone claims to represent. I try to avoid that as much as possible. Certainly there are black communities, black neighborhoods, but I think whenever we hear them talked about in that broad sense, I have a problem with it, because of its political implications.

Of course, the New Deal was limited and social security did not cover domestics and sharecroppers. I am clear on that; I don’t have a problem about thinking through that historically. The problem I have, though, is that this sometimes provides an exit, provides a way to say, “You know what, unlike Scandinavian societies, we’ve got to deal with race and therefore social democracy is not going to work here in the United States.” When we look at the broader history, despite the racism, there are all sorts of instances of popular struggles that are multiracial.

I don’t really know what to make of Obama and Assata Shakur. I suspect it has more to do with Cuba. I am always leery whenever someone mentions the Black Panther Party. I think that the Black Panthers, in it of itself, was limited. I am glad Mel brought up the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. There is a whole pantheon of radical organizations during that period that needs to be discussed and debated, but ultimately, we have to really think about what modes of organizing are appropriate in our own moment.

The question of jobs is the thread that connects a lot of what we have talked about, whether it is the rise of the right or the emergence of the new Democrats, because they have all helped to further this project of neoliberalism in different ways. Speaking broadly about the Left, I don’t think we’ve come up with effective ways of wrestling with neoliberalization. First of all, it is a complicated process; it is tough to summarize. You can certainly talk about the rejection of social democracy, the rejection of the planned state, but what it looks like on the ground sometimes is much more difficult for people to get a sense of.

I think too many of us have gotten caught up in the shadow theater of symbolic presidential candidacies and whether or not Obama is being offended by the Tea Party, and whether we should get upset about it, instead of tackling those kinds of issues that might be included under this notion of neoliberalism. Also, and this is where I disagree with Mel, I actually don’t think the answer is jobs. We are still stuck in a moment in which we want to focus on job creation even though there has been vast technological change that has made some jobs completely worthless and monotonous, work that nobody really wants to do. The biggest task is for us to rethink what kind of society we want instead of thinking in the short term about how to recreate jobs that once existed.

If you go back and take a look at James Boggs’s American Revolution, a book that came out in 1963, there is a key passage where he begins to talk about the kinds of problems that automation would create within society. He is writing about it as somebody who works in the Chrysler plant in Detroit, with respect to the changes that are happening within the plant—how it is intensifying racism as people become more and more insecure about their jobs in the factory, and how it is creating more of a conservative mood among the UAW folks who are now in a posture of negotiation under technological change. He describes in a few sentences the next 40 years of American history. What he basically says is that the changes produced by automation and technological change more generally are going to produce a society in which people are basically disposable and rely upon the state in order to survive. He talks about people being untouchables—essentially he is talking about those black men that he sees more and more often on the street corners of Detroit. They have no possibility of being incorporated into factory production. Boggs ultimately says that what we need to do is get beyond the focus on jobs and begin to talk about a society in which we are no longer organizing our daily lives around the dogma of work. Ultimately, I think that is where we need to go, from a question of how we patch up society by creating minimum wage jobs in the short term, to how we create a society in which there are no disposable people.

Reflecting on this conversation, I am reminded why Platypus on the one hand says, “The Left is dead,” and on the other hand is dedicated to facilitating the development of conditions for the revitalization of the Left. Part of the way I am thinking about this panel is, “black politics in the age of Obama,” but also, “black politics after Obama.” We are historically faced with the question of whether we live in a post-racial society. Answers in the affirmative are, on one level, a manifest lie, and yet they do seem to be descriptively accurate of a highly conservative overcoming of the question of race, in that the question of what kind of politics would be adequate to the question of race, in our epoch, has now simply become unclear.

Part of the reason we look to the American Civil War is because of its centrality to the history of the Left. The transformative moment of the 19th century is undoubtedly the rise of the Republican Party, the Union’s victory in Reconstruction, and the arming of black soldiers and the army as a whole to uproot slavery with blood and iron. Mel was talking about the way in which questions of race seemed in the moment of 1964 to promise a reconfiguration of American politics in the 20th century, a real opening up of democratic possibilities by provoking a crisis within the prevailing, depoliticizing Democratic-Republican dynamic of the post-WWII period. Cedric has talked about the bad legacy of the 1960s—the specters of the 1960s and 1970s. How are we to begin to push on the question of race on the Left, in order to overcome the rotten legacies that lead to our own present incapacity to reconstitute a force that can change society?

CJ: Let me tackle this question of post-racialism first. I think there is a tendency to equate it with the right-wing, colorblind, neoliberal posture, but I think there is some truth to claims of post-racialism. What some people mean by it is that we are post-Jim Crow segregation, that there has been some racial progress in the country. Yet, I think it is overstated to say that because we now have an African-American president, racism is somehow a thing of the past. There is a problem in the way people talk about progress in this country; it seems we have been unable to think through how it is that oppression and suffering continue even in the midst of progress. That some sort of progress has occurred is evident in the fact that we have now seen, as we said before, the expansion of the black middle class and the emergence of blacks within all areas of American life, to a meaningful extent, even if this has not occurred on terms that are always equal to whites. These facts, these aspects of sociological reality, are implied within the post-racial rhetoric. Of course, I reject all the right-wing politics that often goes along with those claims. I hope that what we have begun to do in this conversation is think through the meaning of these changes: the emergence of an expansive black middle class and, with it, the emergence of a black political elite which is part of the local corporate political bloc in any given city. Even nationally, I think we are living in and through a period in which black people are not just add-ons, but an important sector of a ruling class. That is something that has to be reconciled, or reckoned with, in any formidable and effective leftist politics.

We have talked about the decomposition of labor in this country, and with that we have to think seriously about what the working class looks like now in concrete terms, a concern that is easy to lose track of. There is a tendency to get caught up in metanarratives without looking at the specifics. We have to broaden the spectrum of what the American working class is, because there is still a tendency both within the popular discussion but also within certain corners of the Left to settle on an almost Archie Bunker-type notion of the working class—industrial, racist, and ass-backwards—when it actually looks very different in reality. We need to not only think about it in a different way but also to begin organizing accordingly.

We have to sharpen our understanding of who constitutes the working class and also jettison the focus on electoral politics, which has been an undercurrent in this conversation. While instrumental voting is necessary and we should all participate, especially where we think our participation makes some difference, the struggle that we want entails other kinds of organizing—and, it should be said, Occupy does not appear to have been adequate. To put it provocatively, I do not think we can really view Occupy as a movement. It was a series of demonstrations that were powerful and important in terms of galvanizing public attention to the question of inequality in society, but it was largely inadequate. The talk about the “ninety-nine percent” is a good slogan—much like “Change you can believe in.” But neither offers an analysis that clarifies what class actually looks like in this moment.

MR: Within all these changes we’ve talked about, some facts remain. When you talk about any kind of working class movement, you need to talk about women, Latinos, and blacks, who are going to compose the movement. Yet white workers, especially older, white, male workers who by-and-large have reactionary politics, are a problem for the Left and a problem for the working class movement because they dominate the trade unions, as well as the working class communities in which they live. They have a social force that goes beyond their numbers.

So we have to re-conceptualize the working class in a much broader way. But when you do that you have to understand the variety of the working class—why women workers and black male workers are not the same, how different groups of workers have their own interests, aside from their broad class interest, which are really important to them. It is in that context that the black movement is going to have to play a special role. Historically, it has been the most militant movement that has ever challenged the basis of American society. There is no reason to expect that is going to change. That does not mean that the black movement by itself is going to make a revolution. It is not. It is pretty clear now that the Black Nationalist initiatives, however well-motivated they were, did not succeed in liberating the black masses.

We need a black leadership that can mobilize and organize the black masses; until that happens, I am afraid there is not going to be a general progressive movement that is capable of changing much, and that is unfortunate. It is a pessimistic scenario. The objective possibilities are there, the history and the traditions are there, but other factors that were mentioned are mitigating against truly progressive social transformation—changes in work, and the fact that there is now a large black middle class, which does play a conservative role and has an impact on working class people. So, I am not all that optimistic, but I still believe that without a black movement based in the working class, the possibility of a real social change in the United States is foreclosed. |P

Transcribed by Erica Detemmerman, Joseph Estes, and Carlos Matul

[1]. Harold Cruse, “Revolutionary Nationalism and the Afro-American,” in Rebellion or Revolution? Edited by Cedric Johnson (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 74–96.

[2]. Fran Spielman, “Ed Gardner: Black Contractors Should Get Half of CPS Schools Renovation Work,” Chicago Sun-Times 4/9/2013, available at <http://www.suntimes.com/news/cityhall/19380322-418/ed-gardner-black-contractors-should-get-half-of-the-cps-schools-renovation-work.html>.