For liberty and union: An interview with James McPherson

Spencer A. Leonard

Platypus Review 53 | February 2013

Spencer A. Leonard interviewed noted Civil War historian James McPherson, author of the classic Battle Cry of Freedom (1988), to discuss the new Lincoln biopic by Steven Spielberg and the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. The interview was broadcast on January 29, 2013 on the radio show Radical Minds on WHPK–FM (88.5 FM) Chicago. What follows is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Spencer Leonard: 150 years ago, on January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued his famous Emancipation Proclamation. This constituted an important culmination in the long struggle for the abolition of slavery. What, in brief, is the background to the Proclamation in terms of the long struggle for free labor in North America stretching back to the Revolution and into colonial times? Was the destruction of slavery in America simply a matter of coming to terms with an original American sin or a lingering hypocrisy? Or had the course of history in the 19th century posed the question of chattel slavery in a way that it had not done for the generation of the American Enlightenment and Revolution?

James McPherson: Well, in the first place, slavery was not a uniquely American sin. It had existed in many societies over many centuries even prior to its first introduction into Virginia in 1619. In subsequent decades, slavery took deep root in all of the British North American colonies, as it did in the Caribbean and in South America, where in fact slavery was much more deeply entrenched than it was in most parts of North America.

But starting in the third quarter of the 18th century, a variety of forces began to call the morality and validity of slavery into question—cultural forces and intellectual forces and economic forces. The Enlightenment and, with it, the Age of Revolution—the American Revolution, the French Revolution, the Haitian Revolution, the revolutions in Latin America—these began to attack the philosophical and economic underpinnings of slavery. In the northern states of the new American nation, the Revolution led to a powerful anti-slavery movement which by about 1800 had eliminated slavery or had begun to eliminate slavery from all of the states north of the Mason-Dixon line. The Haitian Revolution beginning in the 1790s liberated that island, albeit violently.

So, there was a gathering movement against slavery in the Western world that had a significant effect in the United States, generating a strong anti-slavery movement first among the Quakers, then spreading. It extended not only to the North but to the South as well, reaching a kind of culmination in the 1830s with the beginning of the militant Abolitionist movement—William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, and the founding of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Gradually, that impulse spread into a political movement, first with the Liberty Party in 1840 and then with the Free Soil Party in 1848 and the Republican Party in the middle 1850s. Together these developed what historian Eric Foner talked about many decades ago as a “free labour ideology.” That politics created a sense of two socioeconomic orders in the United States: One in the North based on free labour with social mobility, a dynamic entrepreneurial society; the other in the South based on slavery, which since the 1780s had become more deeply entrenched.

In the 18th century there was a widespread sense that slavery would disappear. The Founding Fathers, who formed the Constitution in 1787, assumed that slavery would soon die out. This is why they were willing to make certain compromises with the slave states to get them to join the new nation. Though the Constitution-makers assumed that slavery would probably die out soon, quite the opposite happened in the South, starting in the 1790s and early 1800s with the spread of the Cotton Kingdom, which meant that in the very decades that slavery was disappearing in the North and a strong anti-slavery movement was developing in the first half of the 19th century, the institution was becoming much more deeply entrenched in the South. That generated a whole series of cultural, social, and political justifications for the institution of slavery. By the middle of the 19th century the two sections had come to a kind of face-off with each other over the question of the expansion of slavery, which had been made an acute problem by the acquisition of a huge amount of new territory in the Mexican War. A bitter struggle ensued, starting in 1854, over the territories that had originally been acquired through the Louisiana Purchase of 1803; the whole question of whether slavery would be allowed to expand into those territories that were not yet states became acute in the 1850s. So, in a sense, the anti-slavery impulse that had deep roots going back into the latter part of the 18th century was coming into a collision course with a pro-slavery impulse that had become pretty powerful by the 1830s and 1840s in the slave states. This led to the showdown in 1860, with Lincoln’s election and the secession of the southern states.

SL: So, at the time of the Revolution and the drafting of the Constitution, there was not among American revolutionaries North and South indifference towards slavery so much as an expectation that the institution would die out. And, indeed, slavery was abolished throughout the North in subsequent decades. But in the South the expectations of the 18th century proved mistaken. That generation did not foresee, for instance, the sort of changes that the cultivation of cotton for industrial production would bring about.

JM: The cotton textile industry was at the cutting edge of economic change in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. There is a real irony here, as the same industrial changes that encouraged the growth of cotton in the South and thus entrenched slavery there ever more deeply also generated—first in Britain and then in Northern United States—the free labour system that came into violent conflict with the slave power in the war.

SL: In 1862, prior to issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln remarked, “I do not want to issue a document that the whole world will see must necessarily be inoperative, like the Pope’s bull against the comet!”[1] Was the Proclamation inoperative, as Lincoln feared? If not, what was the specific import of the Proclamation in the ongoing process of the war’s destruction of slavery as an institution in the United States? What of the clauses lifting the ban on the enlistment of black soldiers in the Union Army? Finally, was Lincoln dilatory in issuing the Proclamation and confronting slavery?

JM: From the very beginning of the war Lincoln had to walk a narrow path. On one side, there were forces set in motion that eroded slavery. These began at the very start of the war: The moment the first Northern soldier set foot in the South he became an agent of emancipation—even if an unwitting and unintentional one—because slaves started flocking to Union lines. Very early the Lincoln administration made the commitment not to return them to slavery. So, starting in the Virginia Peninsula in May 1861 and expanding to many other places as army and naval forces began to penetrate the Confederacy, thousands, then tens of thousands of slaves came within Union lines. The Lincoln Administration was resolved that they would not be returned.

At first, they were not returned only if the owners supported the Confederacy. But by the late summer or fall of 1861, even in the border states that remained loyal to the Union, slaves were not being returned to masters unless the masters could prove, which turned out often to be very difficult, that they were loyal to the United States—and sometimes not even then. Congress also began passing legislation. First there was the Confiscation Act in August 1861. It said that masters whose slaves had worked to support the Confederate War effort but escaped to Union lines—those masters had forfeited the rights to their slaves. In fact, what they meant was that the slaves had become free. Half a year later, in March 1862, Congress passed legislation prohibiting Union officers from returning slaves to their masters, whether those masters were loyal or not and whether this process took place in the Confederacy or in the loyal border states.

That’s one side. The other is Lincoln’s concern to maintain the northern war coalition that included northern Democrats and border state Unionists. Neither of these groups saw this as a war against slavery but only as a war to restore the Union—the Union of 1861 in which slavery existed in half the country. They threatened to withdraw their support for the war if it became overtly and explicitly a war against slavery. So Lincoln had to walk that path. In the first year and a half of the war he sustained the steps I described above by which thousands of slaves did in fact achieve freedom. At the same time he had to make clear that this was not a war for the abolition of slavery, but only to preserve the Union. Any steps that eroded slavery were just a by-product of this war to defend this Union.

In the summer of 1862 the Confederates launched a series of counter-offensives that ended the hopes of a quick Union victory that had spread following Union success in several theatres of the war earlier in the year. The Confederacy was roaring back. It was also becoming increasingly clear that slave labour was sustaining the Southern war economy. Slaves provided much of the labor required by the Confederate army’s logistical efforts. To “strike against slavery as a military necessity” was therefore the phrase used over and over again in the North in 1862. To undermine the Confederate war effort by striking overtly at slavery, Congress passed a more comprehensive Confiscation Act in July 1862. In that same month Lincoln decided to issue a proclamation freeing the slaves in parts of the Confederacy that were at war with the United States. His proposed proclamation would go well beyond the earlier partial steps by which slaves who came within Union lines achieved freedom.

Lincoln was dissuaded from making this overt proclamation at a time when Union armies were reeling back in defeat. He was anxious that it not be viewed as a desperate measure to incite slave insurrection. So he withheld it until after Union armies won a limited but significant victory at Antietam in September 1862. Five days after that battle Lincoln stated his intention to issue a final proclamation on January 1, 1863. This would apply to all parts of the Confederacy that had not by that time returned to the Union. When January 1, 1863, came and the rebellion still persisted in the seceded states, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. It was the culmination of a process that went back to the beginning of the war. In some ways, of course, it went back decades before, back into the long history of the struggle against slavery, the movement to abolish it or at least to restrict its power.

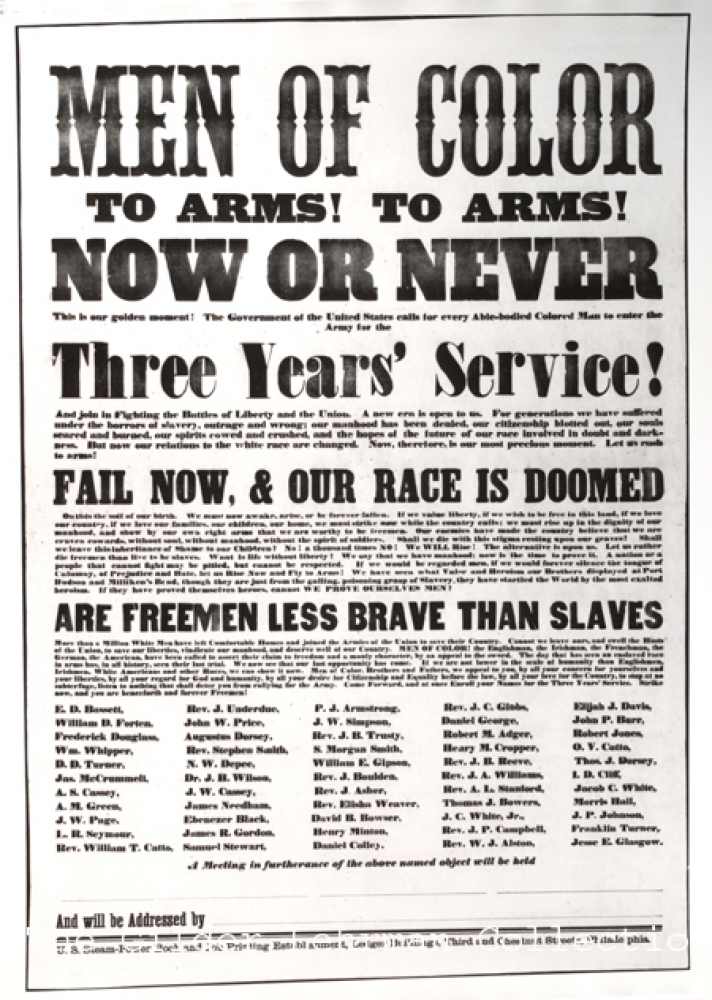

The Emancipation Proclamation had a powerful symbolic as well as substantive impact. It announced that now one of the goals of the war was to bring an end to slavery—maybe not everywhere, maybe not immediately, but it was a much more dramatic statement of purpose than anything that had gone before. It also lifted what had previously been in effect a ban on enlistment of African Americans in the Union Army and announced an explicit intention to recruit freed slaves into the Union army. This added another arrow to the quiver of the Union. In the end, about 200,000 African Americans, most of them former slaves, fought in the Union Army and Navy. As Lincoln himself said on several occasions, these black soldiers made an essential contribution to the Northern war effort. In some ways that might have been the most important part of the Emancipation Proclamation, because now the slaves could not only achieve their own freedom by coming within Union lines but could be armed to fight for their own freedom and for the freedom of the entire slave population.

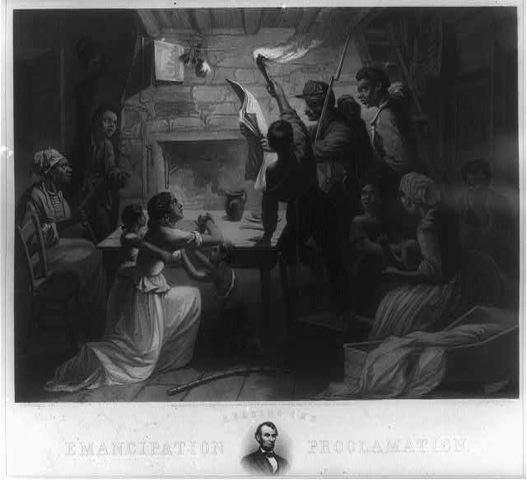

A lithograph of a Union soldier reads the Emancipation Proclamation to newly freed slaves, image from the U.S. National Archives.

SL: Karl Marx’s Civil War writings, many of which were written in his capacity of London correspondent for Greeley’s paper, repeatedly decry the open or at least tacit sympathy for the Confederacy in governing circles in London. It is an aspect of it little remarked upon now, but in its own day the Emancipation Proclamation was as much directed at Europe as it was towards Richmond and the plantations of the South. Thus 150 years ago, on the day the Proclamation was issued, Horace Greeley, editor of what was then the leading Republican newspaper in the country, The New York Tribune, wrote the following[2]:

Our European friends have all desired and hoped that we would take ground against that mother of sedition, that fruitful source of all our woes, Slavery. Victor Hugo, Garibaldi, John Bright—every recognized and honored leader of the party of progress —had impatiently anticipated the Proclamation of Freedom… The policy of Emancipation has won to our cause some valued friends over the water—we do not hear that it has lost us one.

Why was the success or failure of the project to enforce militarily the emancipation of American slaves significant internationally? What was the Emancipation Proclamation’s impact on that plane?

A photograph taken after the Battle of Antietam. Alexander Gardner, “Bloody Lane,” 1862. Library of Congress.

JM: At one level, the Emancipation Proclamation was significant in precluding foreign intervention in the American Civil War. Most civil wars throughout history have attracted foreign intervention. We can think of examples in our own time: Libya last year, Syria right now. There was a real possibility that something of that sort would happen in the American Civil War. If that had happened, foreign intervention certainly would have been on the side of the Confederacy.

SL: There were French armies at the time on the borders of the Confederacy…

JM: That’s right. France had intervened in Mexico in 1861, ultimately sending some 35,000 troops, and in 1864 they installed the Archduke Maximilian of Austria on the Mexican throne. During this time, the Confederates were reaching out to the French and to Maximilian. The French might have provided some assistance to the Confederacy in return for Confederate recognition of Maximilian’s reign in Mexico. That never happened, but it was a real danger.

But the primary fear of the North and hope of the South was British intervention, and, as Karl Marx recognized, there was a lot of sympathy for the Confederacy in Britain, especially among the gentry and the aristocracy. But there was also a countervailing trend of hostility to slavery in Britain. The British had themselves abolished slavery in their West Indian colonies back in 1833. At that time it was the largest single act of emancipation in the history of the world. Within the British working class and among middle class liberals there was a lot of sympathy for the North. After all, for a generation or more before the Civil War the United States was seen by many British workers and middle class liberals as a kind of exemplar of democracy, but with its great, tragic flaw of slavery. So, as long as the North was not openly and overtly fighting a war against slavery but only for the restoration of the Union, it was difficult for those British liberals and radicals to argue that, despite the cutoff of cotton by the war which had caused a kind of economic crisis in Britain, Britain should not intervene in favor of the Confederacy. But once Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, that tragic flaw was removed and British liberals and the British working class could now openly celebrate their support of the Union, and British sympathizers with the Confederacy could no longer use the argument that this was only a war for dominion and not a war for freedom. It became much more difficult to argue that the Union was no better than the Confederacy, that Britain ought to intervene in order to get cotton, that Britain had an obligation to sustain a people fighting for self-government, and so on. So, yes, European and, especially, British opinion was a factor in Lincoln’s decision to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, one major consequence of which was that it put a definitive end to any possibility of military intervention. Such intervention would have been seen as supporting slavery against freedom.

SL: One abiding misconception respecting the war is in regards to its character as a military conflict. Schoolchildren are often told simply that the North had inferior military commanders. But what this leaves aside is the way in which the Civil War was political not only in its aims, but even in its conduct. How does the Emancipation Proclamation grow out of and feed back into the conduct of the war by the Union Army? How did the transformation of the struggle into one for the forcible uprooting of the slave power, signalled by the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation, culminate in Lincoln’s appointment of General Ulysses S. Grant as commander of the Union armies? To take a line from the Speilberg film, how did Lincoln’s Republican Party and Grant’s Army enable each other “to do terrible things”?

JM: Politics and the military are inextricably intertwined. Carl von Clausewitz made the point in his book Vom Kriege that war is a continuation of politics by other means. In the case of the American Civil War, it broke out in the first place because of political differences and a resultant breakdown of the political process. Lincoln was well aware that as President of the United States, as leader of the Republican Party, and as Commander-in-Chief of the United States armies, he was fulfilling both a political and a military role. He knew they could not really be separated from each other.

Early in the war, Lincoln tried to maintain a united coalition of Republicans, of Northern Democrats, and of border-state Unionists for the war effort and he was afraid that any radical steps against slavery would fracture that coalition. But as the war ground on, that equation began to change in his mind and in the North more generally. Steadily demands grew louder from the principal part of his political constituency, the Republican Party, for bolder action against slavery to crush the rebellion—“Bolder action against rebels and traitors!” “Take their property!” And, of course, a principal form of their property was slaves.

So as the war grew harder and more bitter in 1862, the weight of politics became increasingly that of not merely restoring the Union, but of undermining the basis of disunion, which was slavery, the slave power. Lincoln became less and less concerned about maintaining the united support of the various parts of his war coalition and more concerned about striking against slavery and the slave power in order to break the rebellion. That shift in Lincoln’s political calculations resulted in a similar shift in the military.

In the first year or so of the war, Northern generals, and Lincoln himself, tried to avoid destruction of property in the South. He tried to conciliate or win back the support of Southern whites for the Union. But it became increasingly clear that this policy of conciliation or “soft war” was not working. This was especially so, as I have mentioned already, by the summer of 1862, as the Confederacy came storming back from an earlier series of defeats. The pressure grew to “take the kid gloves off” (one of the most frequently used metaphors in soldiers’ letters, newspaper editorials, political speeches in the North in 1862) and turn this into a really “hard war” against traitors. Instead of conciliating the traitors, the military aim was to crush them. This kind of language became increasingly common in the North in the summer of 1862. The Emancipation Proclamation and some of the Congressional confiscation legislation moved in tandem with the change in public opinion and with the actual behaviour of Union armies in the South. Whereas General George McClellan and General Buell, two of the principal Union commanders up until the fall of 1862, went out of their way to avoid hard war measures in the South, generals like Sherman, Sheridan, and Grant in 1864 adopted the policy of destroying anything that sustained the Confederate war effort whether it be railroads or farms or slavery. This was a sharp change not only in military behaviour but in the kind of political will that sustained it. The war aim ceased to be restoration of the old Union and came instead to be destruction of the infrastructure of the Confederacy so as to build a new Union on its ruins.

SL: The recent film “Lincoln” addresses Lincoln the Politician rather than Honest Abe the Plaster Saint or Everyman Lincoln the Log-Splitter. I want to play two brief clips from Spielberg’s movie. The first is Lincoln’s backroom colloquy with Thaddeus Stevens during a party at the White House respecting, in effect, the relations between war aims, strategy, and tactics. The second is Lincoln’s disquisition to his cabinet regarding the necessity of the 13th Amendment, during which he remarks that the hardest thing in politics is to recognize what is required in the here and now. Allow me to play these two clips and have you comment on the film’s portrayal of Lincoln as both leader of the Republican Party and as Commander-in-Chief during the Civil War.

In the White House Kitchen

Thaddeus Stevens: Ashley insists you’re ensuring approval by dispensing patronage to otherwise undeserving Democrats.

Abraham Lincoln: I can’t ensure a single damn thing if you scare the whole House silly with talk of land appropriations and revolutionary tribunals and punitive thisses and thats.

TS: When the war ends, I intend to push for full equality, the Negro vote, and much more. Congress shall mandate the seizure of every foot of rebel land and every dollar of their property. We’ll use their confiscated wealth to establish hundreds of thousands of free Negro farmers, and at their side soldiers armed to occupy and transform the heritage of traitors… The nation needs to know that we have such plans.

AL: That’s the untempered version of reconstruction…

TS: …. The people elected me to represent them, to lead them, and I lead! You ought to try it sometime!

AL: I admire your zeal, Mr. Stevens, and I have tried to profit from the example of it. But, if I’d listened to you, I’d’ve declared every slave free the minute the first shell struck Fort Sumter. Then the border states would’ve gone over to the Confederacy, the war would’ve been lost and the Union along with it, and, instead of abolishing slavery as we hope to do in two weeks, we’d be watching helpless as infants as it spread from the American South into South America.

TS: Oh, how you have longed to say that to me. You claim you trust them, but you know what the people are. You know the inner compass that should direct the soul toward justice has ossified in white men and women, north and south, unto utter uselessness through tolerating the evil of slavery….

AL: A compass, I learnt when I was surveying, it’ll—it’ll point you true north from where you’re standing, but it’s got no advice about the swamps and deserts and chasms that you’ll encounter along the way. If in pursuit of your destination you plunge ahead, heedless of obstacles, and achieve nothing more than to sink in a swamp, what’s the use of knowing true north?

In Lincoln’s Office

AL: I can’t listen to this anymore. I can’t accomplish a goddamn thing of any human meaning or worth until we cure ourselves of slavery and end this pestilential war. And whether any of you or anyone else knows it, I know I need this. This amendment is that cure. We’re stepped out upon the world stage now. Now, with the fate of human dignity in our hands. Blood’s been spilt to afford us this moment. Now! Now! Now! And you grousle and heckle and dodge about like pettifogging Tammany Hall hucksters. See what is before you! See the here and now, that’s the hardest thing, the only thing that counts. These votes must be procured.

What of Lincoln’s political greatness does Spielberg’s film (and Tony Kushner’s script) get at?

JM: In the colloquy with Thaddeus Stevens, Lincoln first of all pays tribute to Stevens’s leadership. Stevens was a radical Republican who from the very beginning insisted this must be a war to destroy slavery and the planter class in the South. As he does in this scene, he frequently expressed his impatience with Lincoln’s dilatory and gradualist approach. Lincoln is here shown acknowledging Stevens’s prescience respecting what the goal of the war had ultimately to be. Stevens was the one who pointed to “true north,” total victory and the destruction of slavery.

Of course, we have no evidence that anything like this conversation ever took place. Still, Kushner here conveys something of Lincoln’s manner of often resorting to metaphor. The compass indicates the direction in which we want to go, but it says nothing about how to get there or how to negotiate the obstacles that will be encountered along the way. As President, he is saying, “You showed me the direction we needed to take.” But, he elaborates, “if I had followed your advice and blindly struck out for true north, we would have lost the support of the war Democrats and border state Unionists, and, ultimately, we would have lost the war.” As Commander-in-Chief and leader of the Republican Party, Lincoln was responsible for figuring out how to get around the swamps and mountains. He justifies his political leadership by saying that this is what he had been doing over the last three and a half years, and had led the country to the brink of abolishing slavery forever. The 13th Amendment was getting ready to pass. Lincoln notes that “it will bring us very near to the end of this long journey.” It’s a brilliant scene that shows Lincoln’s leadership style in contrast with Stevens’s. Both of them were important and necessary. Lincoln’s brilliance was that he recognized how to implement Stevens’s radical vision.

The scene with the cabinet is not true to the reality of Lincoln’s relationship with them. It portrays the cabinet as dragging their feet on the 13th Amendment. That was not really true in January of 1865. Most members of the cabinet were fully committed to Lincoln’s policy. But Kushner uses this scene, nevertheless, to make a historically valid point. Lincoln as Commander-in-Chief demanded that this step has to be taken and that here and now is the time. To use a contemporary metaphor that is much in the news right now, Lincoln says, in effect, “We can’t just keep kicking this can down the road. We must act now and act decisively.” It’s another and important component of Lincoln’s leadership, the matter of timing. There are times when you have to prevaricate and make backroom deals, but there also comes a time when you need to step up to the plate and do what it takes to accomplish the task at hand. In this sense, the scene is very effective even though it is not fair to Lincoln’s 1865 cabinet.

SL: Beyond Lincoln’s presidency, of course, lay peace and Reconstruction. Here, it seems, the contrast between war and peace threatens to obscure underlying political continuities. How did Reconstruction arise as a consequence of the war? We’ve been talking about the connection between the conduct of the war by the Union army and the political project that emerged of suppressing the slaveholders’ rebellion against the federal government. How did Lincoln’s acceptance of the emancipatory logic of the war shape the subsequent project of Reconstruction?

Frederic Edwin Church, Our Banner in the Sky, 1861; Oil on paper, 7.5 x 11.25 in; Fred Keeler Collection, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC.

JM: Reconstruction became an extremely thorny problem for Lincoln, but even more so for his successors. One reason for this is that the word reconstruction had two meanings in the contemporary usage and these were potentially in conflict with one another. In one sense, reconstruction meant to reconstruct the union, to end the war, bring the southern states back in, and to knit the United States together again as one nation. The other meaning denoted the reconstruction of Southern society on a new basis. Now that slavery was gone, the question posed itself: What was freedom going to mean? What was going to be the status of the freed slaves? What was their relationship to their former owners going to be in this reconstructed union? That became the main problem faced by the country for many decades in some ways, most especially during the dozen years after the end of the war, from 1865 to 1877, when federal troops were stationed in the former Confederate states as the agents to enforce Reconstruction.

One way to reconstruct the United States was a degree of forgiveness, of amnesty, of conciliation toward former enemies—that is, the Confederates—in order to entice them to become loyal Americans again. But what would be the fate of the freed slaves if you restored, through conciliation, through amnesty, their former masters, the former Confederates, without any safeguards to protect the freedom of the slaves from some kind of new slavery, some kind of re-imposed quasi-slavery? Such a conciliatory Reconstruction project was what President Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s successor, tried to undertake, and he could invoke some of Lincoln’s legacy by way of precedent and justification. Lincoln had issued a proclamation of amnesty and Reconstruction back in December 1863. In his second inaugural address he had talked about forgiveness and reconciliation. President Andrew Johnson tried to implement that side of Reconstruction to bring the southern states back into the Union as quickly, easily, and painlessly as possible. But the Republican majority in Congress rejected that approach, and I think Lincoln would have come to reject it too had he seen what was happening (if he had lived in 1865 and 1866). At all events, they tried to write a number of safeguards to protect the freedom and expand the civil and eventually political rights of the freed slaves, and that led to a decade, really, of violence and conflict in the south that, in some ways, reversed the aphorism of Clausewitz: The politics of Reconstruction became a continuation of the war. Organizations like the Ku Klux Klan came into conflict with union leagues in the South, organizations of blacks including some former black soldiers. The violence that took place in southern states during Reconstruction was in some ways a continuation of the war. So Reconstruction became a very troubled, controversial, and violent process. Whether Lincoln could have provided the kind of leadership in his second term, had he lived, to avoid the worst of that, is unknowable. Personally, I think he might have. If anybody could have undertaken a more thoroughgoing Reconstruction, he could have!

SL: You are of a generation of historians that emerged in the immediate wake of the Civil Rights Movement. But by the late 1960s, that movement was internally divided with Martin Luther King, Jr. and Bayard Rustin on one side representing liberal integrationism, and Stokely Carmichael and Huey Newton among others on the other side representing an ostensibly revolutionary separatism. So, the fault lines of the New Left seem not to correspond to those of the abolitionist revolution and its opponents in the 19th century. How did the experience of the politics of the 1960s shape your generation’s approach, for good and ill, to the history of abolitionism, the early Republican movement, the Civil War, and its aftermath?

JM: There can be no doubt that the Martin Luther King, Jr. and Bayard Rustin version of the Civil Rights Movement powerfully shaped a generation of historians. I know it shaped my attitude toward the Civil War and Reconstruction. Mine was a liberal integrationist view. Along with others, I have interpreted the abolitionist movement as a liberal integrationist movement in the 19th century. Following on that, together with other historians of my generation, I interpreted Reconstruction as a noble effort to bring about a free and integrated society. This effort passed the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments which, we felt, underlay the civil rights and voting rights legislation of the 1960s. We saw Reconstruction as a kind of tragic failure that had real possibilities that were undermined by Southern counter-revolution, if you will, as well as by a Northern retreat from their goals. What followed was the view that the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s was a second Reconstruction that was now on its way to implementing the liberal and egalitarian goals of the first Reconstruction. I think that the movement toward the New Left, the Black Power movement, Stokely Carmichael, and others in the later 1960s and ’70s, rejected the whole idea that the liberal integrationist movement in the 19th century, the abolitionist movement, the Radical Republicans, and so on, ever had a chance to overcome white racism. For such thinkers equality had been a false promise. Reconstruction was not so much a tragic failure as it was something that never had a chance in the first place. The likes of Carmichael and Newton rejected the sincerity and genuineness of the abolitionists and the Republicans of the 1860s and 1870s. They were just racists, only slightly better than the Southern rednecks. On their view, all of those ideals of liberal egalitarianism needed to be rejected in favor of black nationalism. This view has not had as powerful an effect on the historiography but it certainly had a tendency to influence a good many historians in the 1980s and 1990s. Lerone Bennett’s book on Lincoln as a common, quintessential racist is one example of that.

SL: In his recent book Freedom National, James Oakes speaks of the abolition of slavery in the U.S. as a process of “bourgeois revolution” inconceivable without political leadership and organization. Yet about this revolution, this leadership and the revolution it brought about, the American left has always been ambivalent. Among liberals, there is often a good deal of hand-wringing respecting the constitutionality of measures taken by President Lincoln. Others to their left view the war as somehow compromised or one-sided, an industrialists’ war intended to free the slaves the better to subjugate them to industrial wage slavery. Still others seek to find the overcoming of slavery in a process “from below” that seems to take place outside of the political arena. They praise the abolitionist movement while evincing a certain reticence towards the political and military instruments that movement adopted to defeat the South and uproot slavery: The Republican Party, President Lincoln, and the Union Army. All are suspicious of the enormous growth in the power of the state that resulted from the Civil War and America’s subsequent emergence onto the world stage as a great, ultimately a global imperialist, world power. What is the value in such left criticisms? What to your mind do they grasp and what might they lose sight of? How, if you care to speculate, has the failure to digest (and advance) this history colored or compromised the Left’s subsequent project, whether in terms of the black question and racism or in terms of the politics of freedom more generally?

JM: I think that most of the “hand-wringing” by liberals respecting the constitutionality of Lincoln’s war measures concerns his suspension of the writ of habeas corpus, the declaration of martial law in the North, and the trial of civilians by military courts. At the same time, they tend to approve of his measures to emancipate slaves, including the Emancipation Proclamation, which were based on the same grounds of his war powers as Commander-in-Chief. The suspension of civil liberties probably went too far, as Lincoln himself acknowledged on one or two occasions, but most such actions took place in the border states that were active war zones, with guerrilla warfare and various kinds of sabotage creating circumstances in which martial law seemed the only way to control the situation. Nevertheless, some of Lincoln’s actions are troubling, and created precedents that have been invoked by subsequent presidents with considerably less justification. As for the argument that the emancipation of the slaves was intended to subjugate them to wage slavery in Northern industry, that seems pretty far-fetched to me. The almost universal assumption in the 1860s was that the freed slaves would remain in the South as small family farmers. And, in fact, the large-scale migration to the North and to industrial employment did not begin until a half century after the Civil War. And while it is quite true that the Civil War caused an enormous growth in the power of the state, the central government gave up much of that power in the decades after the war, until it began to grow again in the 1890s and 1900s, in response to circumstances that were quite different from those of the 1860s. The exercise of enlarged government power in the 1860s is something that the Left should approve of, since one of its principal uses was to abolish slavery and enact—on paper at least, and on the ground for a time—civil and political equality for the freed slaves. |P

Transcribed by Wyatt Green, Ed Remus, and Wentai Xiao

[1]. Quoted in James Oakes’s Freedom National.

[2]. Horace Greeley, “The New Base of Freedom,” New York Tribune, January 1, 1863.