Changes in art and society: A view from the present

Mary Jane Jacob, Robert Pippin, and Walter Benn Michaels

Platypus Review 46 | May 2012

[PDF] [Audio Recording] [Video Recording]

On 31 March 2012, the Platypus Affiliated Society invited Mary Jane Jacob (School of the Art Institute of Chicago), Robert Pippin (University of Chicago), and Walter Benn Michaels (University of Illinois at Chicago) to speak on the theme of “Changes in Art and Society: A View from the Present” at the 2012 Platypus International Convention held at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. The complete audio and video recordings of the event are available online by clicking the above links. The original description of the event reads as follows:

Hegel famously remarked that the task of philosophy was to “comprehend its own time in thought.” In a sense, we can extend this as the raison d'être for artistic production, albeit in a modified way: Art's task is to “comprehend its own time in form.” Yet only with the revolutionary rise of modernity can this dictum make sense. Beginning in the 18th century, art sought to register and materialize the way in which social consciousness changed alongside the developing material conditions of social life. Thus, in times of great social transformation, we also bear witness to major shifts in artistic production: The French Revolution and David, The Revolutions of 1848 and Courbet, and the Russian Revolution and Suprematism and Constructivism are three major examples. This panel focuses on the relationship between social and aesthetic transformation.

The panelists were asked several questions in order to flesh out the uneven and at times obscure relationship that art has with a society that is constantly in flux. Full video of the event can be found online at <http://vimeo.com/41013265>. What follows is an edited transcript of the event.

Mary Jane Jacob: Terms like the avant-garde and the underpinnings of modernism are still at the heart of the motivations and activity of many artists—not necessarily in terms of style, but in terms of contributing to changing society. I would like to point to a few concepts at play: a huge part of contemporary art-making is concerned with the dematerialized, not art that is a static object traded on the marketplace; second, it often involves collaboration, which raises questions of authorship on the part of the artist, questions of voice on the part of collaborators, and questions of participation in general; and thirdly, there is a new look to the question of effectiveness in this context—not just the affect of art—and so we should ask, effectiveness to what end?

Here are a few examples. In the 1990s, Christopher Sperandio and Simon Grennan worked with the Chicago Confectioner’s Union at a Nestlé plant to design their own candy bar, including a memorable advertising campaign. The candy bar was sold in stores. Just last night, I was driving south on Halsted; the campus of the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) has changed so dramatically since 1993, when Daniel J. Martinez did a major public intervention there. For all of the 20th century the Maxwell Street Market was a center of a kind of open commerce; then UIC and the city joined forces to make it a campus village. So Martinez’s peoples’ plaza—he knew these redevelopment plans would come in 15–20 years—harkened back to labor events staged in that area, like the McCormick Reaper Strike or the Haymarket riot, along with world events throughout history. The Chicago collaborative HAHA worked on AIDS awareness in their project Flood, teaching kids at once about hydroponics and safe sex, but also coming to a deeper understanding of the epidemic, with each of some 50 members working during the course of the project within the larger AIDS healthcare network. In West Town, Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle’s worked with youth to deconstruct their own images in the media and take control of creating their own images in neighborhood-based forms of presentation, culminating in a huge, 75-monitor video installation along an entire residential block. While the artwork was temporary, it permanently exists in the form of the organization Street Level Youth Media, now about to celebrate its twentieth year.

From 1992 to 1995 the art group Haha cultivated a hydroponic garden, with a focus on nutritional vegetables and therapeutic herbs, in a Chicago storefront.

Though drawn from Chicago, these examples participate in a worldwide movement of artists whose practice consists in taking action into their own hands—sometimes as gestures, sometimes as provocations—in an Alinskian drive to create permanent change. In Puerto Rico, for instance, when the government was about to do away with what they considered a squatters’ village in the mountains, Chemi Rosado painted everyone’s house green so that the community would blend in with the mountain. Kamin Lertchaiprasert and Rirkrit Tiravanija, an alum of SAIC, founded the Land Project in Chiang Mai, Thailand, as a kind of experimental studio for artists, designers, but also for developing bio-gas and other kinds of alternative energy engineering, while, at the same time, farming a rice field with a nearby community that has been devastated by AIDS. Or consider Artway of Thinking, a collective that will be with SAIC this summer, whose projects are often funded by the EU. One project looked at seafarers’ plight around the world and particularly in their homeland of Mestre, Venice. In response to this multi-layered, multi-year art project, a number of actions took place that led to change, among them the creation of two agencies dedicated to services for seafarers and new, more equitable policies regarding access when they are at port. Another one of their projects involved working with 13 provincial governments in Italy to change the law so that people can work legally in Italy while seeking asylum.

We are initiating a research project at SAIC on artists’ social practices in Chicago. My hope is that in the next few years we will explore the relationship between art and social change as it has been practiced in this city and intersects with the thinking and actions here since 1900.

Robert Pippin: The people I look to for help understanding the fate of art in bourgeois society are Kant, Schiller, Schelling, Hegel, the Schlegel brothers, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Adorno, Marcuse, and Heidegger.

The historical events—the simple facts—that define the social reality of the present are not much in dispute. Most count the September 15, 2008 collapse of the massive investment bank, Lehman Brothers—what is sometimes, quite revealingly, referred to as “letting Lehman fail”—as the signal event. It was followed by the nationalization of Fanny May and Freddie Mac, in the hastily conceived, 700 million dollar bailout. With that came the sudden and deep freezing of the international credit markets, the near total ruin of the economy of Iceland, the bankruptcy of Latvia, the destruction, in a little over a year, of what is estimated to be 50 trillion dollars in assets. All of this is well known, but still not well understood. In fact we seem to be drifting rapidly, as if inexorably, back into the same form of finance capitalism that produced the crisis in the first place.

Because these events have not produced even a roughly agreed-upon explanation, their significance remains unclear. The idea that global capitalism may have finally reached its long predicted death spiral is plausible: It appears unable to grow at rates that will provide minimal stability (usually estimated at around 3 percent) and unable to find any novel way to sustain itself without such growth, and all of this for various reasons having to do with unmanageable periodic liquidity crises and the inability of national governments, especially the U.S., to debt-finance its way out of such a crisis, hemmed in by domestic conservatives, foreign creditors, and the massive size of the current deficit—the U.S. has been borrowing at the rate of about 2 billion dollars a day for many years now. That ever more obviously dire consequences will result from our reliance on polluting technology to promote the rapid but deadly modernization that would insure markets for the excess liquidity—or that there may not even be sufficient space on the globe for such expansion—is, I think, a depressingly persuasive argument. And it is persuasively made, by David Harvey in The Enigma of Capital, for instance, whose account I am relying on.

But our question today concerns changes in art and society, and, presumably, the implications for the production and appreciation of art works in the current situation, understood as a now perhaps unending crisis in financial markets, with its attendant high unemployment, right-wing populism, and hyper-dogmatic religious enthusiasms that, in the U.S. at least, seem to be the first manifestation of dangerous, perhaps permanent political instability. Asking about art in this context seems necessary, yet almost impossible to think about.

The category “art” still takes in everything from folk art to commercialized pop art (music, television), to extremely expensive gallery art for an ever-smaller and richer elite, to highly academicized art music (each piece of which is performed, I am told, an average of once), to ambitious and not-so-ambitious graphic novels, to self-consciously avant-garde installation art, and so on. I don’t know how to begin to get a handle on the issue except by ascending to a high altitude and talking about the “present” in much broader terms than those sketched above. Specifically, by talking about the present in terms of the situation of bourgeois society, after the basic institutions necessary for that society began to come into view in the mid-19th century and afterwards, many aspects of which were the subjects of realist and modernist art. I mean by this the establishment of a domain of privacy created mostly by the bourgeois nuclear family; the establishment of the political public sphere; the reconstruction of marriage around the romantic love of partners, eventually equal partners who chose their own mates; what was so famously, and what still should be called, the fetishization of commodities; the establishment of mass consumer societies based in nation-states; and the increasing reliance on technology to produce the expansion and growth necessary to sustain competitive market societies.

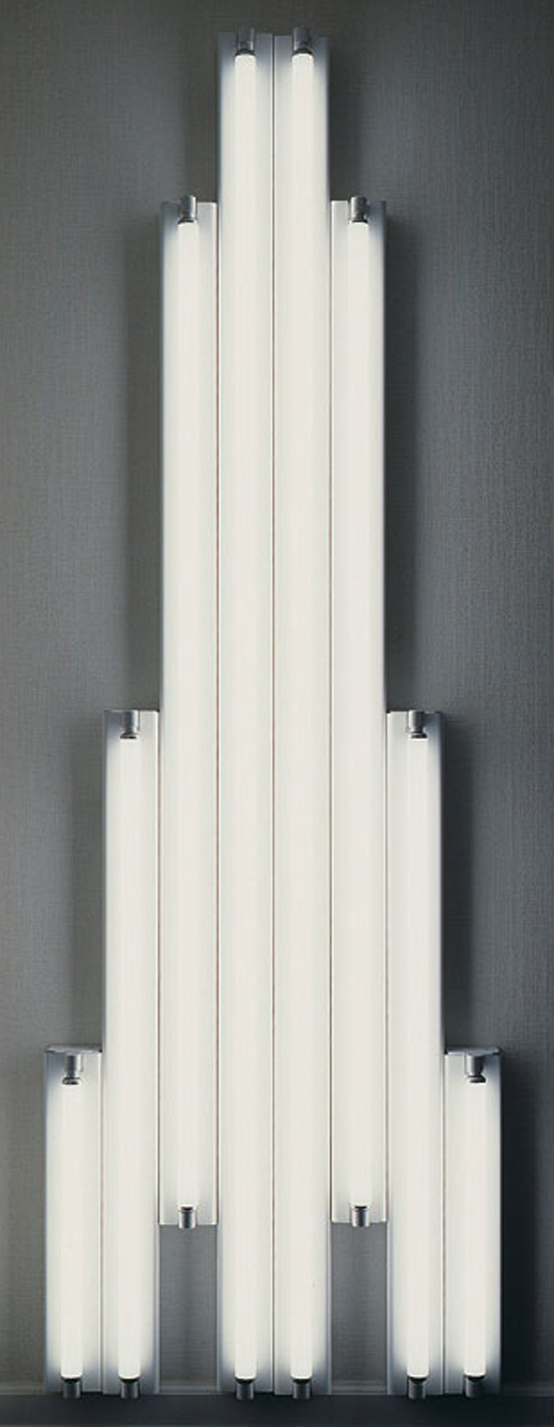

I will assume that many of these aspects are well known and uncontroversial. But at that altitude, we can also say something equally abstract and, at such a level, a bit banal, about art. If we accept that in earlier forms of Western societies, works of great artistic genius were possible—a highly contested claim—then it has become a commonplace to say that the form of life coming into view in Paris and London in the mid-19th century made the production and appreciation of art of that quality, or at least the consensual recognition of such art, much more difficult. Perhaps there might be such art, but the importance of there being such art, its significance, would have changed radically and would have been greatly reduced. Something like this might have been Hegel’s position, which was the first to claim that in modern bourgeois societies, the greatness of art had become a thing of the past. For others, the social institution of art was eventually unable, after the failure of the heroic resistance of high modernism, to resist its commercialization, commodification, and eventual trivialization in the likes of Damien Hirst or Dan Flavin.

Damien Hirst, Pharmacy, glass, faced particle board, painted medium density fiberboard, beech and ramin woods, dowels, aluminum, pharmaceutical packaging; dimensions variable, 1992 (Tate Modern).

I don’t mean to refer to anything much about the implications of the commodity form of value, as such, but to another, deeper problem. The production of art works—let us say, easel paintings—inevitably assumes the possibility of some shareable and non-discursive but primarily sensible, affective, form of intelligibility. If there isn’t such a distinct form, there isn’t art. Moreover, under the historical assumptions about meaning influentially insisted on by Hegel, the conventions necessary for such assumptions to be reasonable change over time. At some basic level, we need to understand that change before we can understand the possibilities of its specific modalities, like aesthetic modalities of shareable meaning.

These same considerations are in play in other bodily incorporations of meaning, for instance in the bodily movements we count as actions. There is some kind of crisis if actions taken by agents to be of certain types are not taken to be such actions by many others. Rousseau began an account of those conditions and their implications: Modern societies had created novel and profoundly deep forms of dependencies, in a novel and profoundly deep way—most famously, but not exclusively, the dependencies that result from ever more divided, specialized, and thus alienated labor. To make Rousseau’s long story short, this situation created a great social pressure for ignoring, for suppressing via conformism, for rendering invisible by various means the vast social inequalities that such unequal positions of dependence and relative independence would inevitably produce. This is the situation that would later be intelligibly called “dialectical.” The social relations and fundamental inequalities of modern capitalism greatly weakens the possibility of common conventions that could be shared in meaningfully fulfilling ways; rather, these sorts of tensions tended to be anaesthetized by a conformity-inducing redirection of human desire to what everyone else desired.

From Hegel to Adorno, the realm of the aesthetic has been called the realm of the negative—that which is not expressible in discursive articulation and so possibly resistant to those processes of conformism. For Hegel, “negative” did not mean unintelligible, but involved bearing truth in its own way, preserving some distinct mode of genuinely shareable meaning, or at least an aspiration for genuinely shareable meaning. The first expression of the crisis of aesthetic modernism was such negativity: the diminishing credibility of the traditional aesthetic forms that had previously made possible such sensible mutual recognition. The painterly conventions of illusionism, perspective, sculptural modeling to evoke solidity, or the traditions of genre, the nude, the ideal—these are all refused, all at once, in Manet’s Olympia, for example. Aesthetic intelligibility would from now on be immensely more difficult because continued reliance upon such conventions came to evoke conformism, a kind of enforced traditionalism, in the face of the looming possibility that prior assumptions about shareability of meaning were becoming irrelevant.

The events of 2008 have not changed any of this, and have added, as an even more effective conformity-inducing phenomenon, a shared mood—namely, deep anxiety—and the kind of neurotic, racist hysteria we see in the Tea Party movement. What we should expect is, at the very least, something very simple: that the occurrence of great art—art that means in a way that escapes the kind of social conventions necessary for a mass consumer society to sustain the conditions of its own survival, but still manages to embody a kind of shareable meaning not anticipated and normalized by such conventions—will be extremely rare. Perhaps so extremely rare as to be acknowledgeable and appreciated only many years after its appearance.

Dan Flavin, “monument” 1 for V. Tatlin, fluorescent lights and metal fixtures, 8’ x 23 1/8” x 4 1/2” (243.8 x 58.7 x 10.8 cm), 1964 (Museum of Modern Art).

Walter Benn Michaels: Maggie Nelson’s collection of poems, Jane: A Murder, centers on the murder of Nelson’s aunt Jane in 1969, four years before Nelson herself was born. At the time, and for a long while after, it was thought that Jane’s death was one of what were thought to be the “Michigan murders”: seven young women killed in Washtenaw county, Michigan, over a period of two years. In 1970 a man was arrested and convicted for what turned out to be the last of the murders. The assumption was that he had probably killed Jane. And Jane itself, the book, is written on that theory. As the book was going to the press, however, Nelson learned that a different man had been arrested for Jane’s murder. Her next book, The Red Parts, is about the trial and conviction of that man. Edgar Allen Poe makes an appearance in The Red Parts. Watching a TV show about the murder of a “beautiful Peace Corps volunteer in Tonga,” Nelson was taken aback to hear someone on the show explain his obsession with this crime by referring to Poe, who “once declared the death of a beautiful woman to be the most poetic topic in the world.” But while Poe was only incidental for The Red Parts, he is central to Jane.

One way that Nelson imagines this centrality is as a critique of Poe’s sexual poetic, which she suggests in an interview is an example of what she calls the ethically unsound practice of treating beautiful women as if their lives were “more grievable,” because somehow more valuable, than others. Hence it matters to her that Jane, unlike the Peace Corps volunteer, was not particularly beautiful. Indeed, she puts Jane’s picture on the cover of the book at least partially to prove it. But the picture plays another role as well, one that matches the other interest Nelson has in Poe. As she tells the interviewer, Poe made this comment in his Philosophy of Composition while describing, with what seems to be at least some glibness, how to make the perfect poem. The ambition to make the perfect poem—which is, she says, also a part of her book Jane—is not easily dismissed. The idea that a woman ought to be beautiful is one thing, the idea that a work of art ought to be perfect is another, and the idea that the beauty of a work of art is its perfection is something else. Nelson herself insists on this difference. A poem near the end of Jane begins, “Does it matter if I tell you now that Jane was not beautiful?” It goes on to describe Jane, her skin, white and chalky, her eyes set close together. It ends with a description of Nelson’s favorite photo of Jane, her face half bleached out, and the point is no longer that Jane is not beautiful, but that the picture is beautiful. The poem’s last words are, “the whole picture is beautiful.” The beauty of the photo is made out of someone who is not beautiful. More precisely, the kind of beauty the photo attains has nothing to do with the kind of beauty that the person in the photo might or might not have. This is emphasized by the insistence that it is the “whole picture” that is beautiful; the invocation of the whole calls attention in particular to the form of the work of art, to its ambition to be perfect, in a way that no person can ever be. We might say that just as the photograph of Jane must be made beautiful even though its subject is not, the poem Jane must be made into a whole even though the occasion of its production, Jane’s death, is loss.

There is a difference between the question of whether the person needs to be beautiful and the question of whether the poem ought to be perfect. This difference might plausibly be understood as the difference between a set of ethical or even political concerns, and a set of aesthetic ones. For example, the question of whether some lives are or should be more grievable than others might be understood as political in a way that the question of the possible beauty or perfection of the work of art is not. But this opposition, emptying the aesthetic of the political, is certainly not one that Nelson would herself accept, and in fact we might better understand the politics of the grievable as opposed, not to a set of aesthetic concerns, but to another politics, for which the question of grievability would not arise, or at least would not be primary. Similarly, we might understand the aesthetic of perfection as opposed, not to the political as such, but to another aesthetic, distinguished by its repudiation of the commitments that accompany the entire intellectual apparatus of perfection.

In photography, the most brilliant and influential exponent of the aesthetic of the grievable would be Roland Barthes, for whom the most important thing about the photograph, the punctum, was the element that shoots out of it like an arrow and pierces the beholder. That is why the most important photograph in Barthes’ wonderful book about photography, Camera Lucida, is the one we do not see, as it is not in the book: the picture of Barthes’ mother. The reason we do not see it is that it would not pierce us; she is his mother, not ours. For us, he says, “It would be nothing but an indifferent picture.” When Nelson reproduces the photo of Jane, she is going against both Barthes’ practice—Jane was her aunt, not ours, but she includes the photograph—as well as his theory. It is the picture defined in terms of its internal relations, face and torso against the sky, and thus turned into a whole, that Nelson finds beautiful. It is, in other words, the picture disconnected from the interest its beholders might have in a beautiful Jane, or even a Jane they might be drawn by the poem to grieve for. For Barthes, our indifference to his mother makes her picture not worth reproducing, but our indifference to Maggie Nelson’s aunt is the desired response. It is precisely the imagination of the beholder’s indifference to the person Jane that marks the ambition to achieve perfection in the poem Jane. If the aesthetic of the whole is thus the aesthetic of indifference, the politics it evokes is also, I want to suggest, a politics of indifference: namely, indifference to worries about whether beautiful women should be more grievable than others, or whether anyone should be more grievable than anyone else.

The question of Jane’s beauty and the critique of the idea that it should matter belong, as Nelson herself suggests, to a feminist politics, and more generally to what she calls the cultural moment of the triple liberation of the Civil Rights Movement, the Women’s Movement, and the Gay and Lesbian Rights Movement. These represent liberations from the idea that the lives of white people, straight people, men, are more grievable than others’. The refusal of these hierarchies, the refusal of the hierarchy of grievability, is in Nancy Fraser’s useful shorthand “the politics of recognition,” a politics that is given further specificity by the distinction Fraser makes between recognition and redistribution. This distinction is not itself an opposition, of course; there is no logical contradiction between recognition and redistribution, no reason why a politics seeking to eliminate or minimize class difference could not collaborate with a politics seeking to respect racial and sexual difference. But in practice, beginning in the 1970s, there has been no such collaboration. On the contrary, in the years during which the triple liberations had become central, not only to progressive politics, but also in varying degrees to American society itself, economic inequality of the kind that would be addressed by redistribution, rather than recognition, has radically increased. The increase in inequality, the increased immiseration of the American working and non-working classes, Black, White, Chicano, and Asian, is a phenomenon that does not date to 2008, but on the contrary dates to somewhere between 1969 and 1974 or 1975.

One way to understand the differing fates of recognition, its increasing centrality in redistribution, its increasing marginality, might be just a question of emphasis. In its commitment to social justice, the Left has, for various reasons, focused on issues of identity but not on issues of class for the past generation, at least. Part of the utility of the concept of neoliberalism, if we accept its periodization as primarily a phenomenon of the mid-1970s, is that it helps us see what is misleading about that way of putting the point. It helps us to see instead that the commitment to anti-discrimination at the heart of liberal politics is also at the heart of neoliberal economics, and has been ever since Gary Becker argued that an employer’s racism could only add to his labor costs since, for example, the refusal to hire black labor increased the cost of white labor. Following this line, virtually all neoclassical economists understand racism, sexism, and heterosexism as obstacles to success in competitive markets. This argument about efficiency has been doubled by an ethical argument against preferring one prospective employee over another on the basis of any characteristic not relevant to doing the job. That is, economic commitment to the primacy of markets has been accompanied by an economic and ethical commitment to equality of access to those markets. Thus, far from opposing neoliberalism, the commitment to anti-discrimination is foundational for it. This is not to say that anti-discrimination is always or sufficiently defended in all cases, but only that sexism and racism, and increasingly all inequalities of access to markets, like homophobia, are understood abstractly to be both unproductive and wrong. Inequalities actually produced by those markets, unlike inequalities of access to them, are not understood by neoliberal economics to be wrong. By this I mean just that the increasing economic inequalities of neoliberal societies are a problem for neoliberalism only insofar as they are raced or gendered. Those critics whose way of protesting economic inequality consists precisely in focusing on disparities between men and women or Black and White—think of every complaint about the disproportionate poverty of minorities, every complaint about the glass ceiling—are defending the ideals of neoliberalism, not criticizing them. They are protesting the ways in which the raced and gendered subject has been classed; they are not protesting class itself. Another way to put this is just to say that racism and sexism are liberalism today functioning badly; when it is working well, you get economic inequality, which has nothing to do with our feelings of whose lives are more or less grievable.

Just as an alternative to the aesthetics of the grievable is an aesthetics of indifference, the alternative to a politics of the grievable is a politics of indifference. That is, inasmuch as the goal was to minimize inequality, what a class politics requires is redistribution of wealth without regard to the race and gender of the beneficiaries, without regard to whether we see them as inferior, without regard to our regard itself. That is why today it is only as form that art does class. Produced by capitalism, rather than racism or sexism, poverty is independent of how we feel about or see the poor, just as the formal unity in the photograph Jane is independent of how we feel about the person Jane. In fact, that independence is the very meaning of the photograph’s unity, of its being a whole. It is in this context that the ambition to produce a perfect work of art has taken on a political meaning and that it has the particular political meaning it has. For the perfect work is one that, asserting the difference between it and the world, asserts its autonomy, an autonomy that in our period may be understood as above all autonomy from—here thematized as indifference to—its reader or beholder. It is the production of the work of art’s difference from the world that counts as the work it does in the world.

Q&A

Professor Pippin, I wonder where a figure like Hölderlin fits in your narrative and, with him, the Romantic notion of the possibility of the transcendent? It seems to me that the crisis of art in modern bourgeois society is also tied to the crisis of religion. Secondly, do the panelists see a parallel between the high modernist aesthetic and what one might call a high modernist politics, which aimed at the abolition of capitalism? In what ways does this differ from a postmodernist aesthetic?

RP: Hölderlin is usually taken to represent a moment of rejection of the emergent forms of civil society that were visible in the early 19th century. He is seen in terms of a nostalgic retreat driven by a deep sense of the fragmentation, disunity, alienation, and anomie of modern life. That is the traditional and perhaps typical reading. A different reading would hinge on a very difficult issue: the politics and the cultural valence of the aesthetic ideal of the beautiful. I say this because Hölderlin certainly represents the last fluorescence of an approach that attributed real philosophical depth to the Beautiful. That approach would begin to evaporate after the 1820s–1830s, in the last gasp of the German Romantic Movement. Central to that approach was the conviction that the possibility of the presentation and experience of the beautiful intimates an actual harmony between the fundamental disunifications of modern society, between sensibility and intellect, reason, understanding, and so forth. One way of answering your question is just to say that something like the historical fate of Hölderlin, tied as it was to aspiration of the beautiful, had something to do with the fate of the beautiful, which in the modernist movement ceased to have the same credibility as an aesthetic ideal as it did for the Romantics.

If what you say is true and one presupposition, acknowledged or not, of high modernism is complete non-complicity with the commodification essential to capitalism, then you have to ask what the position of refusal is supposed to entail. If you believe that there is at bottom no reformable moment internal to late capitalism, what do you do, as an intellectual, if there is no longer the Party? That is, after all, the situation that begins to emerge after the failure of the German Revolution in 1918, and intensifies in subsequent moments—the dates 1939, 1956, 1968, 1989, and others stand out. If you’re an intellectual who believes that there is no internally reformable trajectory visible in modern capitalism, what does the rejectionist stand that you attribute to high modernism actually entail, politically? That is a question for which no one has a good answer, really.

MJ: Can I just ask, are there other artists here in the room? It is unfortunate in panels like this that there is often not a full sense of what contemporary artists are doing, what work they are making. What are their motivations, ethical stances, and commitment to change? Instead, some here are working from a historical position. At the same time, we need to have a pre-modern, a pre-museum, a pre-market sense of what we mean when we say the word “art,” and how some essential reasons for making art still function for artists in society today. As with the examples I pointed to earlier, the actual practice of many artists today seeks join art with life, even to dissolve any such barrier. This has been such an important theme in modernism and essentially in all art.

I want to read something from Foucault that articulates my disappointment in the inability to locate our discussions in what artists today are actually doing. Foucault says, appropriately, “What strikes me is the fact that in our society art has become something that is related only to objects and not to individuals or to life. That art is something that is specialized or done by experts who are artists, but couldn’t everyone’s life become a work of art? Why should a lamp or the house be an art object, but not our life?”

But my co-panelists’ presentations still address art as objects, when what Foucault points to is what many artists are dealing with now, which often doesn’t involve art objects at all—at least in the traditional sense—much less worrying about how individual art objects will perform in the market.

WBM: Foucault has been very influential, but actually is one of the early exponents and defenders of neoliberalism. Post-modernism is and has been the more or less official culture of neoliberalism. No doubt, post-modernism is in some sense an avant-garde, but the idea that it has been a politically useful avant-garde is completely mistaken, in my opinion.

I think it is important to go back to the question that Robert was raising, a question I don’t have an answer to, but which is highly significant: He said art, great art, at this moment is going to be rare, and that sounds right. On the other hand I’m very much struck by the fact that there has been a kind of renewal in the last decade, and I think it’s probably above all in photography.

MJ: To clarify, there is the work of art that you’re referring to, which is done by the artist, and then there is also the work of the artist. Not all artists make works of art, per se. Being such a capitalist society, we unfortunately have fewer outlets for artists to be doing that kind of work, because such work doesn’t necessarily involve the creation of a discrete “product.” Moreover, a great deal of art today does not seem interested in participating in the discourse around the question, “What is great art?”

If art offers a way of understanding the possibility for freedom in modern life, characterized by free labor and free love, and if the difficulty of discerning great art in the present speaks to conditions of conformity that affect us all, how do you see the art and artists you have referenced as offering us a real hope of an emancipated future? To what extent do you feel confident in their present transcendent capacity to shed light on the possibilities of our moment?

MJ: Back to the notion of context, an aesthetic object might give us a sense of freedom, but what happens on our way to even having an experience with that art object? How are we free to even have experience and what do we understand experience to be? When we pay 18 dollars to get into the Art Institute, we enter it knowing that accessing these objects is worth a certain amount. How does this affect our experience of the object? I am interested in artists like Seamus McGuinness who spent five years working with a psychiatrist in Ireland developing the Visual Arts Autopsy to change policies, procedures, and laws within that country, addressing its post-Catholic crisis and the stigmatisms around suicide. The more-than-one-hundred families’ participation in those aesthetic moments of the Visual Arts Autopsy gave them an enormous sense of freedom, agency, and chances for personal change, as well as coming together to institute change.

RP: One important distinction seems to transcend the notion of produced works of art that could be or could resist being commodities, and your life as a work of art. I think the immediate question that one needs to ask, which I would argue is inevitable once the entire category of art is invoked, is not what it would take to make your life a work of art, but what it would mean to make it a successful work of art? There has to be a difference between attempting to make your life a work of art and failing, and attempting and succeeding. Perhaps there is another difference, in succeeding very well. The thing I’ve tried to argue very briefly today is that the possibilities of successful art are actually not self-definable by the artist. This has something to do with the issue of the avant-garde, but it also—more fundamentally, I’d argue—depends on shareable conditions for the possibility of non-discursive but nonetheless articulable meaning in a community at a given time. Art has a particular modality of rendering things intelligible. It is non-discursive and it is largely sensible and affective, even as it lends itself to certain forms of discursive articulation. The reliance of artwork of a historical period on various conventional conditions for the possibility of such shareability seems to me inevitable. It is at least conceivable that at certain stages of history it might be reasonable to think that the conditions for such shareability have been so distorted and degraded that it’s very unlikely that anything other than the minimal satisfactions of the conditions of art would prevail.

Art addresses itself to us as individuals, whereas politics by necessity addresses us in some sense as a collective, as humanity as such. I felt like the tension between those two issues, the relationship between the individual and the collective as addressees of art and politics, came out in different ways in each of the talks. Good politics doesn’t assume that the state of humanity in the present is the only possible state of humanity; does good art assume the same?

About the materialist account of art, I would say that art is an object not simply in the sense that it is a thing the artist has made, a “product,” but also in terms of what we might call the “social being” in the work. It seems like an artist can’t really get around the commodity form of the art object today, given that the predominant form of production today is commodity production. In this context, the socially engaged art practices I’ve seen recently seem driven to eliminate metaphor as a way of communicating, and so the art relies on this direct, one-to-one relationship between itself and the audience. A lot of it is about getting across a “message”—usually, a message concerning the lack of and need for services that the state once provided, but no longer does. On the other hand, with a Hegelian account of art, I feel like there is a problem the degree to which it posits a type of artist who doesn’t really know what he’s doing, but who simply gives form to things that don’t really quite have a form. Such an account seems to imply that it may be better that the artist is completely unaware of what he’s doing, so that later on it’s available for and completely open to interpretation. In such an account, how would it be even theoretically possible for an artist to self-consciously produce a work that’s adequate to the material conditions we live in?

MJ: Metaphor is something that creates possibility for shared experience, I think. But we also have to look at process. An artist’s process can be deeply invested within a place or within a constituency with people, with their activities. Process can look like the back-and-forth dialogue of permissions and checkpoints as a work develops, as with McGuinness’s project. The work of art also offers possibilities for reflection, and sharing that reflection. Our own, individual interpretation of a work of art, both deepens our relationship with the work and becomes the basis for communicative possibility—moving us, as Dewey would say, to the art’s ultimate ends of participation and communication. Your own life that you draw upon for such communication is your experience. You don’t necessarily need the art history, or other information; you just need to be aware, remain present in the experience. I’m interested in the possibility of works of art as this kind of mode of social communication.

WBM: If we think about art and politics in terms of the history of art, the question being raised is, what does it mean to make great works of art? Foucault has that well-known remark, which is that people ordinarily know what they do and why they do it; what they don’t know is, what does what they do, do? I think the artist has a pretty good idea of what he or she is doing in making these works—there is the sense of trying to make something like the perfect work of art, with an insistence on form. What I am suggesting is that there is a certain kind of work today that has both the capacity to produce major works of art and the capacity to produce an interesting, significant critique of our contemporary moment and that, in the main, these are not works of art that as their point take up the business of trying to help people. These are works of art that are produced as an attempt to make great works of art.

MJ: The fact that artists don’t know what the work does comes directly as a definition of art. I don’t think it is controversial to say that art involves both a creative act on the part of the artist and a re-creative act on the part of the viewer, and that those are more or less equal ends. The work of art is not finished when the artist finishes with it.

RP: The “German idea” is that works of art, as works of art, are essentially liberationist: They are connected deeply with the aspiration for the realization for freedom. What that means is an enormous and very thorny issue, but one that has come to the surface several times in our discussion. The idea that there could be a sensible embodiment of an intended meaning that is uniquely sensible, but shareable, evokes a resolution of the central modern antimony concerning freedom: We are corporeal, spacio-temporal objects, and at the same time we are subjects. With respect to our discussion today, the idea is that art preserves the possibility of this unity, as a kind of anticipation of its full realization, and this anticipation consists in the moment of actual sensible embodiment of an intended meaning in the artwork. The reason it’s supposed to be a moment of potential liberation is that the circulation and shareability of that meaning is in some way to be viewed, can be viewed, as the expression of free and equal subjects in a communicative relation of a sort that isn’t in the interest of anyone. Stating it so baldly makes it seem naïve, perhaps. This wouldn’t mean that art would not involve ideas, nor does it mean that the artist must remain ignorant of those ideas. However, I do think it is hard to imagine how art made—“in advance,” so to speak—specifically in service of certain ideas, could serve the ideal of freedom that this framework articulates. Nor is this freedom art points to, in this conception, simply the occasion for the individual to explore his or her own psyche; it is not the freedom that self-expression, per se, can express. This aspect I’ve tried to draw attention to, this shareability without the interests of anyone being served by the regime of shareability, is the aspiration that art embodies just by being art.

The discussion of the German idealist notion of freedom makes me wonder about fascism: Can great art be reactionary?

RP: I think of art as a normative term. That is, fascist art is not art; it’s just a façon de parler to call it art. It doesn’t achieve the conditions of art, so it’s not art. But then, of course, you would raise the question: How do you distinguish between bad art and good art? To put it most radically, there’s no such thing as bad art. Rather, that art which doesn’t achieve the condition of art, is not art.

WBM: Many of the major modernist poets of the first half of the 20th century completely understood themselves as fascists. Ezra Pound would only be the most obvious example. We could think of this as a discrepancy between Pound’s aesthetic commitments—that is, the kind of art he thought he was trying to make—and his political commitments. However, he himself was entirely convinced. Indeed, many lines in the cantos do explicitly profess sentiments that could only be attributed to Italian fascism. If you’re going to say that it can’t be great art if it’s fascist then you are going to have to say either Pound’s Cantos suck—which is a very implausible claim for anybody who is interested in the history of poetry—or you’re going to have to say that the thing that makes them great art somehow disconnects them from the fascism that they themselves profess. There is no question, moreover, that fascism had a profound aesthetic component; however, it does not follow from this acknowledgment that there are therefore great works of fascist art.

MJ: This, too, is a question in the design field. What is good design? One could conceivably create a very well-designed crematorium in a Nazi death camp. So we come to a question of values and ends. I think we work from personal values, which come about in terms of our position and our perspective within society. Those are things that form personal ethics and larger civic ethics. Those have everything to do with making art, making design, and living life.

WBM: Indeed, it raises the question of the relevance of the artist’s ethics, and even of the artist’s politics, to the politics of the work of art. I am skeptical of the idea that people’s political intentions and political motives have much to do with the politics of the works of art they produce. However, their aesthetic intentions, their aesthetic motives, have a great deal to do with their politics. |P

Transcribed by Carolyn Graham and Divya Menon Kohn