The occupation of art’s labor: An interview with Julia Bryan-Wilson

Chris Mansour

Platypus Review 45 | April 2012

On November 28, 2011, Chris Mansour interviewed Julia Bryan-Wilson, Associate Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art at the University of California, Berkeley and the author of Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam War Era (2009). Mansour and Bryan-Wilson talked about the history of the Art Workers' Coalition and its political relevance today, in light of the increasing involvement of artists and artistic strategies in the Occupy movement. What follows is an edited transcript.

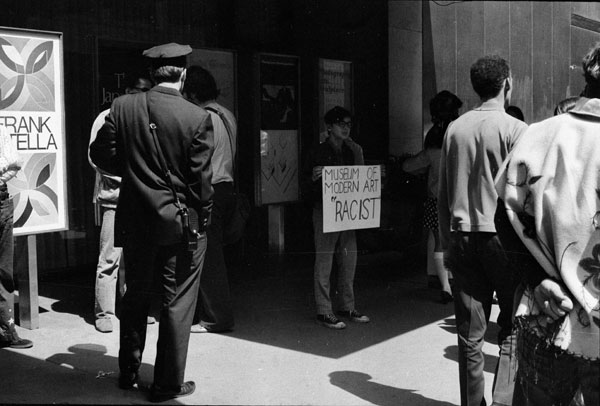

Art Workers' Coalition (AWC) with the Art Action Group (GAAG), and the Black & Puerto Rican Emergency Cultural Coalition stiking outside the MoMA in 1970.

Chris Mansour: How did you come to study the artwork of what you call the “Vietnam War Era” and its relationship to the Art Workers' Coalition (AWC)?

Julia Bryan-Wilson: In the beginning—when I was still a young graduate student—I was drawn to a performance by the Guerrilla Art Action Group (GAAG) that occurred in the lobby of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1969. It was a bloody, visceral action that called for the immediate resignation of all Rockefellers from MoMA’s Board of Trustees. At the time I was thinking about performance art as a form of protest, and how bodies in space—occupying space—meant to register certain activist concerns. Digging further into GAAG, I learned more about how they functioned as a direct action offshoot of the AWC. I wanted to do a project about the AWC, perhaps plumbing its history and laying out what really happened there, because there had at that point only been scattered accounts, and most of them were by people who were involved themselves, so there was not much critical distance.

To me the AWC was a compelling, if short-lived, organization. I was also very intrigued by how many artists and well-known figures within the circle of contemporary art criticism participated in it. So it was not just people like Carl Andre and Dan Graham, but also critics such as Gregory Battcock, who was the editor of significant anthologies about “minimal art” and “idea art.” Some critics like Lucy Lippard and what were referred to as “low level curators” also saw themselves working within and amongst the AWC. But my focus shifted the further I delved into my research, and increasingly moved away from a strictly chronological account of the AWC towards larger questions of the politics of artistic labor in this moment, a moment when labor itself was radically transforming because of a shift to a postindustrial age. To me the intriguing question became not, “What happened to the AWC?” but rather, “How did understandings of artistic labor change in the wake of the formation of the AWC?” Also, how was artistic labor and broader political activism in mutual dialogue for a few key figures, such as Lippard or Hans Haacke? With my book, Art Workers, I never set out to write the comprehensive history of the AWC, but instead to think about the redefinition of artistic labor through figures that are very influential in contemporary art history, whose work has never been substantially talked about in relationship to this activism.

CM: The main redefinition of artistic labor, as you elucidate in your book, starts with the distinct division between art and craft during the Renaissance era, as articulated by the art historian Michael Baxandall. But art as a form of labor really takes sway with the development of capitalism as a social structure. You reference a lot of Marx’s writings on art as labor in your book to make this case. You also mention the Artist Guild in England in the 1800s, the Artists Union in the 1930s, and so on. How did these diverse conceptualizations of art as a form of labor influence the AWC, and how do you see the AWC’s understanding of art as a form of labor as differing from older aesthetic concepts?

JB-W: Those involved in the AWC had many different, and quite uneven, levels of sophistication regarding Marxist theory. Some of them knew nothing about Marxism, and were kind of going along with the flow or absorbing things that were ever-present in the atmosphere of the times. Others, like Carl Andre, were rather more serious students of Marxist theory. Of course, Marxist theories are also contentious and contradictory with regards to how art might or might not function as a kind of labor under capitalist forms of production. Even for Marx himself there is some friction regarding the role of patronage, creating a product for a potential market, and how making art might be understood as “free” or unalienated labor. So when artists turned to what was often half-understood Marxist theory in the late 1960s to call themselves workers, it proved to be fairly unstable ground.

But the people in the AWC did have some historical precedents regarding the relationship of art and politics: They knew something about the Russian Constructivists, who called themselves “art workers.” They also knew a lot about the WPA moment and the Artists’ Union in New York, because some of those involved were still around. But the AWC was founded during a totally different cultural context than the Artists Union in the 1930s. The WPA employed artists under the rubric of a state sponsored program. Artists in the 1960s–70s were working with strongly anti-governmental precepts, and it was difficult to make the WPA type of artistic labor fit their vision, since that was, in their minds, akin to making Social Realist murals under the guidance of a corrupt state. Those in the AWC wanted to be free to make recalcitrant art like Minimalism and Conceptualism. But they still wanted their work to be considered a form of labor.

Artists' Union

CM: You also note that the members of the Artists’ Union—who were employed by the government—were substantially wage laborers, whereas a lot of the artists in the AWC and those affiliated with it supported freelance workers. So was it the case that the kind of political mobilization that the AWC had to seek out was qualitatively different in nature than the Artists’ Union given the structural changes of capital?

JB-W: It had to be different. The issue, which I even see today, is that there were calls to “occupy, organize, and unionize.” However, one question the AWC could never quite resolve was, “Who are the employers that you are directing your demands to?” When artists were wage laborers in the 1930s, there was actually a target: the U.S. government. So the artists could actually go on strike and withhold their labor if they wanted. Artists had some collective agency, in part, because there was a body to which they were clearly accountable. A rather more volatile question is, “How is art productive in society?” If artists today withhold their labor, who does it impact, exactly? The 1930s, the 1960s, and 2011 are crucially dissimilar. I hope the current Occupy movements continue to take into account the meaningful differences between these historical moments.

CM: What are the fundamental advantages and disadvantages you see in the strategies enacted by the present-day Occupy Museums movement? Is their historical imagination really following the footsteps of the AWC, or are the similarities unfolding haphazardly, or coincidently?

JB-W: For one thing, the AWC started in 1969 primarily around the issue of artists’ rights in museums. It is important to know that the kernel of its idea came from artists who felt their work was being put in contexts that they disagreed with, and that they were not being compensated fairly for how their work was displayed and distributed. It therefore started with concerns about the procedures and policies in places like MoMA, which was of course a highly powerful institution even in 1969. However, the AWC moved quickly into hosting a series of open hearings where hundreds of people aired complaints precisely about the question of the relevance of museums, and about how to formulate a kind of political-artistic practice. People had extremely divergent ideas about this. Some people wanted the museum to wither away, others wanted alternative methods of art distribution to flourish, others wanted to just infiltrate museums, and others just wanted “their piece of pie” and were happy if their work was shown at places like MoMA. So these disparate views were one of the fundamental contradictions that led to the AWC’s demise.

On the other hand, museums were absolutely central to what the AWC did, including the question of racial diversity, which was one of the primary items on the list of the AWC’s demands. The AWC called for greater representations of African American and Puerto Rican artists. A little bit later, the AWC also realized that gender inequities should be a focus of their activity. It also pushed for artists to be on the board of trustees of the museum, and advocated for greater transparency of museum procedures, and so forth. Part of my argument in Art Workers is that the artists of the AWC were a major part of instigating a broad institutional critique of how museums were run and managed. Given the centrality of the Vietnam War and the acceleration of anti-war activism at this time, it was easy for the AWC to realize that these issues were interconnected, in part because there were very powerful connections between museum trustees and the military-industrial complex, notably the Rockefellers.

The AWC focused a lot of their demonstrations in the space of the museums, such as protests within the MoMA or strikes outside on the steps of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, trying to shut down the Met for one day after the U.S. bombings in Cambodia. But the history that has not been talked about as much are the moments that the AWC tried to think not only about art issues. Artists at that time also tried to strike with the postal workers, and marched for abortion rights, issues that were not actually in the purview of the art institution or the art world, but, rather, were about building broader solidarities. Those moments are intriguing, and, in some ways, these actions arguably diluted the art workers movement, but also invigorated it in important ways.

CM: When or why did political ideology start to clash? You mentioned the instance when Robert Morris was interested in showing solidarity with the construction workers, but his interaction with them indicated a difference in ideologies. Could you elaborate?

JB-W: These questions are alive today: Think of the Occupy demonstration in solidarity with the Teamsters when art handlers at Sotheby’s went on strike. These issues of labor and how art is a productive force in the economy are still central. But activist organizing around economic questions cannot be merely about asking, “When do I get paid?” That question is extremely limited, and it is one that exposed the limitations of the Art Workers’ Coalition. Obviously the question of compensation and value is critical, and everyone should be valued for the work that they do. But if it comes down to just making lists of demands about individual needs, the critique is a lot less compelling, and not necessarily about how we re-envision society, inequality, and economics in the widest possible sense. What was interesting about the AWC was the sense that there were broader struggles that mattered alongside and in concert with the art industry, for example the Vietnam War, questions of race, class, and gender.

CM: This seems to raise the age-old problem between reform and revolution, and highlights the differences in ideology that encompass the whole organization. Since the AWC never really came to adopt a broad vision of how they sought to change society or express some kind of future vision, these absences may have been subject to its downfall.

JB-W: There were all kinds of ad hoc committees and splinter groups forming, in part because the AWC failed to develop a self-critique of how it conducted its own business. There were a lot of black artists and white women who felt like it was becoming a platform for grandstanding by white male artists.

No less than in 1969–71, those questions about ideology and reform versus revolution are critical today. In addition, some of the people in the AWC were on the cusp of becoming famous, and as they began getting more institutional support, they felt less urgency regarding the questions of exclusion that had once compelled them.

An Occupy Museums protester at Zuccoti Park, wearing a guerrilla mask in reference to the Guerrilla Art Action Group (GAAG).

CM: We could bring this back to what we see going on with Occupy Museums because a lot of the political rhetoric of the group is “anti-hierarchy.” Do you see a lot of similarities between the moment of the 1969–71 and Occupy Museums?

JB-W: Those similarities are some of the hopeful things about Occupy. I don’t think we need a rigid voice to come down from up high to say what the crucial issues are, what the goals should be, or to lend it more shape. Right now, the inchoate form of it is the most exciting aspect, because it’s a space of potential and openness. Partly, what we're seeing is a new calibration regarding historical shifts in the economy, and I think artists feel the move towards precarity palpably—especially adjunct art teachers, or artists having to scrap together bare minimum wages to support their practice. At the same time, we need to maintain a thorough analysis of how art is different from labor. First of all, there is no one type of work and no one type of worker; these are not monolithic constructs. Simultaneously, art is itself a category that is fragile and tenuous. It is challenging to place someone who sells hand-thrown ceramics at a craft fair together with someone who is in the Venice Biennale: the markets are different, the value structures are different, the gendered valences are different, etc. So there is a huge range here, from what might be called the “low” to what we think of as the “high,” in levels of production, levels of cultural capital, levels of access, and the question of free time. We have to be careful to not collapse all these things, even as it is helpful to consider the moments of vital connection between all modalities of making. The moniker “art worker” has always been contradictory. Art, in some regards, maintains a distinction from other forms of labor because of its unruliness. So let’s not pretend that there is a total symmetry there. In fact, one of the helpful things about the phrase “art workers” might be that it contains within it some kind of explosive juxtaposition, some reminder that those words are held in tension, and I don’t want to see that antagonism get smoothed over.

In the past, there was more clarity on the stakes of what was being fought for and who the logical targets might be. For example, it’s curious that Occupy cares so much about museums or biennials, when museums or exhibitions are not necessarily where the production of culture is at its most visible or vital. The art world has really expanded, and there are so many other alternative sites where these issues are being addressed and debated. Museums used to be a central forum for questions of democratic ideals; they were seen as political institutions that have a trust or mission to a public, a pubic defined in its broadest and most optimistic terms. But hasn’t that ceased to be so, for the most part? At this point the imbrication of corporate interest and art institutions is the air we breathe. Museums are no longer seen as sacred or vaunted institutions; they are hybrid spaces like any other, riven with compromise.

There are still pertinent questions that need to be asked regarding labor in the art world, of course. For example, it is crucial that people are now publically asking what it means to be an art handler, to have your labor go unrecognized, when that work is critical to the function of the institution. And there is a push to think about art schools producing incredible student debt loans. I am not sure museums are the places where those questions will be answered. Museums are of course critical reservoirs of culture—I am not advocating that we ignore them or give up on them—but there are a lot of other spaces currently being activated that could also be addressed.

CM: This touches on the issue of what kind of culture is being produced and in what context. The general terms that seeks to politicize artistic labor today is “cultural producers” (used often in the e-flux crowd, for instance). This redefinition, it can be argued, replaces the category of “art worker” in order to include forms of cultural production that are not relegated to the fine art arena. How apt do you think the term “cultural producer” is as a mode to politicizing artistic—or cultural—labor? Could trying to politicize all forms of cultural production in this way be casting the net too wide, or, is this a politically important move for today’s conditions?

JB-W: As much as Dadists and others tried to dismantle it in the 20th century, art is still a category that has a lot of built-in assumptions about taste, class, privilege, gender, and so on. So to widen art, to turn it into “cultural production” as a further expansion of artistic labor is, on the one hand, an important move and it does understand that culture gets produced in all kinds of forms. Cultural production could include musicians as well as teachers, and so is interestingly broad. Yet it doesn’t have the same kind of political charge that “art workers” has. As I said, if we can recognize that “art workers” as a phrase is loaded with tension, rather than taking it at face value, then it has a certain traction. I think the term “cultural producer” does a different service, as it does remind us that culture is a specialized model of production.

The self-descriptor “art worker” has recently been given a new life among some artists who rally around the 99 percent. I am fascinated by how that phrase disappears and then reemerges in moments of crisis. Because of the Occupy Art and Labor sub-group, the collisions between art and work have a fresh resonance. So it will be curious to see what people do with the idea of the art worker, where it goes, how people make distinctions between artistic labor and the “creative class,” which is also a category that has gotten a lot of attention recently.

CM: Artists like Carl Andre and Robert Morris were entrenching their art or their kind of performative social existence in stereotypes of the working class, e.g., Andre wore overalls and dressed like a “working class” laborer, while Robert Morris incorporated a lot of working class machinery and construction methods into his art production. What were these artists trying to convey?

JB-W: It was one of the basic shifts of the New Left to define itself in opposition to what they perceived the Old Left was about: rank and file, union politics, and organizing blue collar laborers. The New Left had a different focal point, which was more about students, drafting off of the Civil Rights Movement, and questions of identity. I think people in the 1960s understood rightly or wrongly that the working class was no longer the subject of revolutionary change—because they were mollified by high enough wages, because of mass infantilism through popular culture, and so forth. That’s the pessimistic and cynical view. There are all kinds of condescending texts you can read that were written in the 1960s, in brutally ugly terms, about who the working class folks ostensibly really are, and how they are no longer the people to care about in terms of political organizing.

Art workers were navigating this complex terrain. In some ways, blue collar manufacturing was becomes less important in terms of the U.S. economy—and terms like post-industrialism, immaterial labor, service work, and knowledge production were coming into focus. Some people in the AWC had nostalgia for the working class, because they were personally familiar with it, and their own personal affinities problematized any clarity vis-à-vis their own class status. This romantic affiliation with the working class is part of what made the moment so complicated. The idea that the artist is a working class man is a longstanding trope with the avant-garde, stretching back to Courbet, for example, or David Smith as a member of the United Steelworkers of America.

In the 1960s, however, there was growing confusion regarding who the working class actually was. Carl Andre in his overalls is a visible registration of the change of guard from the Old Left to the New Left. He’s wearing his overalls, and he has this formal affiliation with the working class through bricklaying, but at the same time he is adamant that his work is artisanal. He wants to align himself with the working class, but at the same time he understands that his art has nothing to do with that kind of labor. Similarly, this sort of tension led to the massive break within Robert Morris’s work circa 1970. He created a massive installation that was made with construction materials, in concert with construction workers. But then in the middle of his exhibit’s run, there were the well-publicized “hard hat riots,” where construction workers appeared pro-war and repressive, and Morris closed his exhibition down early as part of the Art Strike. The hard hat riots seemed to prove that the working class was actually promoting regressive demands. To me this illustrates the contradictions of that moment: Inserting whatever you think of as working class procedures into your art doesn’t necessarily make you one of them.

CM: In the 1970s, after the deflation of New Left’s student movements such as the SDS, many students believed it was important to redirect their political attention towards more classic concepts of working class politics. However, if we consider what artists and art institutions were interested in politically, issues surrounding multiculturalism and identity politics really shaped the art world following the New Left in the 70s. Can it be argued that this trajectory was even more of a divergence from grounding the art world’s politics on class issues?

JB-W: It points to a rupture in a structure that was already somewhat untenable. Some in the AWC urged a feminist perspective or demanded racial inclusivity in art institutions, such as building an African-American wing of the Museum of Modern Art—which never happened. At the time, those political goals seemed a lot more achievable than they might now. Most people in the AWC were never comfortable with the idea of fomenting revolution alongside, say, postal workers. Most of their concerns actually revolved around institutional inclusivity. In fact, most postal workers, and what we might simplistically call the working-class in general, did not want to have anything to do with the artists. There were aborted and failed attempts at solidarity by artists to include the working-class proper in their struggles. When protesting at the Met, for instance, artists called out to construction workers to join them, but the construction workers never did. The workers felt that the artists did not speak to their own concerns, that the artists’ political demands were not the same as theirs—it was never apparent how each group’s burning issues related to each other. These moments of thwarted solidarity happened again and again, which brings up the issue of who is mobile enough to assume multiple identities, to move in and out of the category of “worker” at will. There is a privilege embedded in the decision to adopt that category as a performance rather than to see it as a category that exists within the capitalist system, one that hails certain subjects quite specifically and fixes them in place. It is like a costume that Andre could easily step out of. His level of cultural privilege and access is starkly unlike someone who is normally a mason.

CM: The other notable thing about those whom you refer to as the Vietnam War era artists is their desire to distance themselves from the avant-garde model, which also sought to politicize art. It is curious to see them shift away from modern avant-garde approaches, but nonetheless maintain an interest in still drawing from its canon, for example the Minimalists that were associated with the AWC are influenced by Constructivism. Why do you think there was a push–pull relationship towards avant-garde approaches during this era?

JB-W: The term “avant-garde” during this time fell out of favor in part because it was heavily associated with Clement Greenberg’s ideas of Abstract Expressionism. By the late 1960s, there was an Oedipal desire to react against that category. The Minimalists and Conceptualists, for instance, really wanted to disavow the idea that the avant-garde was purely elite and removed from popular culture. Even though Conceptualism seems high-minded or esoteric today, its original impetus was meant to be populist and democratic. The idea was to get art out of the museums by recirculating it, having it being easily available, and allowing art to be made by basically anyone. Greenberg’s idea of the avant-garde cast a long shadow that these artists wanted to step out of. A bit later, in 1973–74, scholars affiliated with the AWC—i.e. Max Kozloff and Eva Cockroft—wrote exposés about how Abstract Expressionst works were used ideologically by the U.S. State Department during the Cold War, seeking to triumph the superiority of freedom of expression in the U.S. against the Soviets. Ironically, most people recognize a painting by Pollock as legitimate art, over a postcard by, say, the conceptual artist On Kawara, even though Lucy Lippard and others claimed that conceptual work had the potential to be more populist and democratic than Abstract Expressionism at that time.

According to some arguments, there was no real avant-garde in the second half of the 20th century. Benjamin Buchloh, among others, theorizes the “neo-avant-garde,” positing that art in the last few decades is a form of return to an earlier moment, iterations with slight differences. Greenberg might have speculated that the cultural conditions that would make a true avant-garde possible have faded away, as there is no longer a distinct patron class and so on. In his essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” from 1939, Greenberg talks about the paradox that the ruling class supports the avant-garde, as artists are attached to the elite via an “umbilical cord of gold.”[1] That structure has been so re-organized that it no longer makes sense to talk about the avant-garde in the present—it is a historical category and that historical moment has passed.

Robert Morris' Mirrored Cubes (1965)

CM: It seems that the minimalist artists and conceptual artists were in some ways an avant-garde gesture themselves in trying to advance beyond the historical avant-gardes. Many of the arguments about the relationship of art and politics gained a new life for these practices. Lucy Lippard in her later writings said that art should be ditched altogether in order to mobilize it for political gestures and spreading information, which was extremely counter to the modernist notion of keeping art autnomous from direct political activity. What was the relationship between art and politics during the Vietnam War era?

JB-W: The AWC did include artists like Leon Golub and Nancy Spero who were coming from the political figurative tradition in a recognizable way. But the AWC also consisted of artists who were deeply invested in abstraction and more obdurate, advanced forms that did not have a directly legible political content, even though they very much proposed a new ethics of spectatorship, which has been their lasting legacy. The classic example is Robert Morris’ mirrored cubes from 1965. When you see them, you see yourself looking at them and in relation to other people looking at them in a specific space. This is distinct from modernist ideas of viewership, where you were supposed to be taken away from yourself or use the work as a window into another world, or where you were glimpsing the artist’s subjectivity. Such conceptions of viewership have been theorized by Michael Fried in his essay “Art and Objecthood,” where he explains his notion of “presentness”. Fried thought that this kind of viewing experience with minimalist art was very agressive. It kept you very much aware of duration and the temporal aspect of spectatorship. I think Fried is right in claiming that minimalism creates these experiences, but I disagree with his negative judgment about it. This change in viewership is exactly what is transformative about minimalism. It paved the way for conceptualism and institutional critique, which recognizes that art is activated in distinct times and places and does not transcend its own context. It insists that the viewer ing something to the experience of art.

What I tried to do in Art Workers was to open up a lens to see how the works were part of the larger economic and political sphere. For instance, I researched where many of the materials minimalist artists used came from. Some of the magnesium plates that Carl Andre used for his floor sculptures were made by Dow Chemical, and Dow was under a lot of scrutiny in the 1960s for its terrible labor practices, and its connection to making napalm. Those factors of process and manufacturing can be highly veiled. They do not make themselves legible when you look at the art, but they are the necessary conditons for the art to come into existence. Such material conditions are important for art historians to investigate. We need to probe the sometimes literal, physical factors that go into the art’s making, as part of global and socio-economic practices bound to capitalism. In one way Andre’s floor scultures drastically brought art down by elimiating the pedestal, providing viewers the ability to walk upon its surfaces, etc. All of these things are potentially transformative for the way art is typically made and displayed. You cannot, at the same time, look at his floor works and immediately claim them to be an overt protest to the Vietnam War. They do not work ideologically in that way. But, on the other hand, you could say they are political because they propose a certain kind of leveling and viewership, and because they take part in an economic material system which the Vietnam War was deeply implicated in. |P

[1]. Clement Greenberg, “Avant-garde and Kitsch,” in The Collected Essays and Criticism, Volume 1: Perceptions and Judgments, 1939-1944, ed. John O’Brian (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 10. Available online at <http://www.sharecom.ca/greenberg/kitsch.html>.