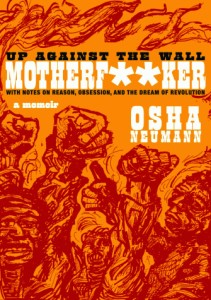

Book Review: Osha Neumann, Up Against the Wall, Motherf**ker: A Memoir of the ‘60s, with Notes for Next Time.

New York: Seven Stories Press, 2008.

Philip Longo

Platypus Review 28 | October 2010

WHAT WERE THE 1960S? The Left is still a bit confused. Activist and lawyer Osha Neumann, in his memoir Up Against the Wall, Motherf**ker, suggests that the 1960s not be thought of as a single coherent movement, but rather as a collection of movements gathered under the umbrella of “liberation.” The civil rights movement overlapped with the anti-war movement, but they were not fully aligned. Similarly, the politically earnest Students for a Democratic Society often came head-to-head with the counterculture and the seemingly more radical tactics of Neumann’s own group, the Motherfuckers.

Yet, despite his gesture toward distinguishing among different strands within “the sixties,” Neumann himself falls into the same trap as many New Left revisionists in documenting his time in “the movement.” The Motherfuckers participate within a mass structure of feeling, “a wet dream of possibilities” during a period of “unrelenting urgency.” Neumann’s sixties are marked not only by political struggles within the Left, but also by a kind of vague collective consciousness. This mutes Neumann’s political narrative and renders it difficult for him to disentangle particular political currents and goals from one another. Looking back, he describes the period as marked by the confluence of revolutionary movements and feelings in a “strange amalgam, [in which] the image of the revolutionary transformed by the revolution fused with acid fueled visions in which all things melted and morphed, all permanence dissolved and nothing withstood change” (162).

While Neumann’s book provides an interesting glimpse into the history of the political movements of the 1960s and a possible case study in activism, the elusiveness with which he treats “the sixties” contributes to the confusion of the book’s second part, the “notes for next time.” Rather than helping us out of the seemingly intractable dilemmas facing the post-1960s left—how do we understand the period so we can learn from it and build on it or, alternatively, discard it and move on?—Neumann’s book reenacts the Left’s ambivalence toward the decade and its failure to reconstitute an emancipatory leftist politics. Like many a 1960s memoirist, Neumann is still unsure what to make of his experience, how to disentangle history from what merely happened. Reluctant to throw the flower child out with the bathwater, Neumann, like the Left, becomes stuck in a cycle of recrimination and nostalgia.

As Neumann tells it, joining the radical activist group the Motherfuckers was part of a rebellion against his upbringing. The son of intellectual émigrés Inge and Franz Neumann who fled the Holocaust and found refuge as professors at Columbia University, Osha (originally named Thomas) grew up in the New York émigré circles occupied by other German Marxist and Frankfurt School intellectuals, like his father’s friends Herbert Marcuse and Otto Kirchheimer. When the author was 14, his father, who authored Behemoth, the classic Marxist analysis of the Nazi state, died. Shortly after, his mother married Marcuse. Growing up in the extended orbit of the Frankfurt school, Neumann writes, “I concluded that my birthright was an all encompassing theory, Marxism, which sought to determine, in each historical period, the forces which represent humanity’s hope for liberation and a just ordering of human affairs” (15).

Having the author of Eros and Civilization and One Dimensional Man for a stepfather made adolescent rebellion difficult. Still, after an admittedly apolitical tenure at Swarthmore and graduate studies in history at Yale, Neumann began to turn away from his leftist inheritance towards what he describes as the passionate embrace of sex and art. Becoming preoccupied by his own “irrational” sexual passions, Neumann saw in revolutionary activism a mirror and outlet for all that seemingly defied the rational theorizing of his parents’ circle. As he puts it, he could not reconcile “reason’s strict demands to prioritize thinking over doing with the unruly energies of my corrupt, insistent body” (17). Art, sex and activism became his rebellion against the “theoretical” bent of his family. Neumann’s rebellion, unlike that of some of his peers, was not an ideological struggle or awakening, but rather a full-throttled embrace of praxis over an irrelevant and crusty theoretical tradition.

And full-throttled it was. After dropping out of Yale and moving to the Lower East Side in Manhattan to become an artist, Neumann became involved with the Angry Arts Week against the Vietnam War in 1967. Arrested during an event where a poster of a maimed Vietnamese child was unfurled during Sunday Mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, he describes himself as having a “mystical experience” in jail. But rather than changing his life course, this experience seems to have confirmed the direction in which he was already heading. Chanting in jail along with his fellow demonstrators, he felt his new insight allowed him to turn his back on “rationality.” If instrumental reason could not stop the bombs in Vietnam, and had in fact created them, his jailhouse epiphany suggested that the only way to fight back was to embrace the irrational. And so he threw off the dialectic in favor of direct confrontation.

In 1968 Neumann joined the new underground “affinity group,” Up Against the Wall, Motherfuckers, which grew out of the Angry Arts Week and Black Mask, another revolutionary artist group founded by anarchist Ben Morea. The Motherfuckers took their name from a famous line in the poem “Black People!” by Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones):

You know how to get it, you can get it, no money down, no money never, money dont grow on trees no way, only whitey’s got it, makes it with a machine, to control you you cant steal nothin from a white man, he’s already stole it he owes you anything you want, even his life. All the stores will open if you will say the magic words. The magic words are: Up against the wall mother fucker this is a stick up![1]

Though the group was primarily white, drawing from the drop-outs and street kids of New York’s Lower East Side, much of their tactics and style were lifted from the Black Panthers. Describing themselves as an “affinity group devoted to liberation and revolution through any means necessary,” they adopted a stance of extreme militancy. Ideologically they were hard to pin down. If the SDS could be thought of as attempting to lay out the ideological framework for the rebellion, the Motherfuckers, lacking the patience for their hesitancy and abstract theorizing, saw themselves as the soldiers.

At times deliberately incoherent in their actions and views, the Motherfuckers understood themselves as rebelling against “The System,” a phrase that denoted “more than the economic and political institutions by which the rich wage unequal war on the poor, stealing the fruits of their labors, and despoiling the earth in the process.” In theory “The System” meant “the totality of reality as shaped by, dependent upon, and supportive of those institutions… presidents and penises, the Pentagon and our parents, desires and disaffections, torturers and toothpaste” (66). In practice, as Neumann would later admit, “The System” referred to anything that was not, or did not agree with, the Motherfuckers.

The most interesting part of the book is Neumann’s inside view of power struggles and confrontations with the Lower East Side police, the occupation of Columbia in 1968, the 1968 Chicago Convention, and the “liberation” of the Fillmore East theater, a venue for the new multi-media psychedelic rock concerts so popular at the time. In these sections, Neumann presents some astute reporting with commentary, disavowing many of the more violent and ineffectual forms of protest. Looking back, Neumann calls much of the Motherfuckers’ politics vague both in its ecumenical anti-authoritarianism and its “infantile” rebellion. To this extent the book represents Neumann’s attempt to work through the consequences of this criticism: “It is easy to dismiss this politics as nothing more than childish tantrums, and to profess a baleful acceptance of the status quo as more ‘mature.’ It’s more difficult to disentangle, delicately, as one would a bird caught in a net, the genuinely radical and uncompromising elements in this politics from those which are self-defeating” (93). This statement is certainly compelling, if only because it reveals the book’s greatest weakness: Neumann is unable to perform the operation he prescribes.

The memoir portion makes up the first half of the book. The second half is comprised of essays on the legacy of the 1960s, the 1999 WTO protests, and an engaging essay on the academic left’s fetishization of what it calls “theory.” Yet these “notes for next time” are suggestive at best. Other than his gradual return to an embrace of “Reason” (albeit coupled with action), Neumann offers little in his assessment of what lessons we would have to learn to follow through on the ambitions of the best 1960s radicals. Nor does he compellingly argue that such a historical critique and re-appropriation is even desirable. Rather, Neumann simply assumes that any reconstituted left must be modeled on the 1960s movements, albeit with some revisions:

We purged as an infantile aberration the extravagant imagination of unlimited possibilities that inspired our most heroic—or foolhardy—acts of disobedience. But the vision doesn’t really die. The wet dream of possibilities imagined by the counterculture of the Sixties is real, even now, as we struggle to avert an equally real nightmare: fascist regression, the triumph of unreason, the death of nature, the extinction of hope. Our flame smolders underground, waiting for the wind that will fan it back to fury. (165)

In critiquing the methods of groups like the Motherfuckers, Neumann misses a chance to take on the political ideals of the movement. In collapsing fascist regression, the triumph of unreason, the death of nature, and the extinction of hope all into one giant bogeyman, Neumann rehearses the Motherfuckers’ gesture of collapsing all sources of unfreedom or inequality into “The System. ” In short, by attacking the methods rather than the analysis of their historical situation, Neumann seems to believe that all that the Left needs in the contemporary moment is quite simply to pick up where the New Left activists left off. While decrying senseless violence and “infantile rage” Neumann clings to a sense of historical possibility that arose out of the 1960s—surely, a necessary thing today. However, by clinging so fervently to this dream deferred, Neumann becomes blinded by his own nostalgia and recriminations.

This surplus of nostalgia and recrimination is the legacy of the ineffectual left today. Another, related legacy is our current incoherent politics, unable to distinguish between “presidents and penises” or “the Pentagon and our parents”—that is, unable to effectively understand our own historical moment. We are still unable to distinguish between the various sources of unfreedom, where they intersect and where they do not. By insisting on the “The System” as the enemy and a renewed and revised activism to combat it, Neumann’s analysis, like that of the contemporary Left as a whole, leads to the type of random and ineffectual activism we ultimately regret, but at the same time cannot quite let go of. |P

[1]. “Black People!” Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones), in The LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka Reader, ed. William J. Harris (New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 1991), 224.