Strict interpretations: A reply to Atiya Khan

Manan Ahmed

Platypus Review 20 | February 2010

TO QUOTE ALDOUS HUXLEY and to paraphrase Atiya Khan in her Platypus Review article “The poverty of Pakistan’s politics,”[1] I represent “a sad symptom of the failure of the intellectual class in time of crisis.” In Khan’s telling, it is the intellectual Left which failed (in) Pakistan, and under its sad banner now congregate blind and mute liberals such as myself. It is a strong, and harshly delivered, criticism and I take it very seriously.

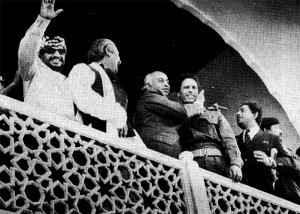

Yasser Arafat, Sheikh Mujibar Rahman, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, Muammar al-Qaddafi, and an unidentified man at the second meeting of the Organization of the Islamic Conference held in Lahore, Pakistan in 1974. After promulgating an explicitly Islamic Constitution in 1973, Bhutto hosted the conference to launch a new, Islam-oriented diplomacy for Pakistan.

Let me begin, however, by engaging Khan on her reading of Pakistan’s past. Khan posits that there was once a golden age of Left-labor politics in Pakistan, which gave the newly created state a “backbone” in the first five years of its existence. This was a time when trade unions “flourished” in industries across Pakistan, so much so, she argues, that some two hundred unions could claim over 400,000 workers as rank-and-file members by 1951. This golden age of labor curiously coincides, according to Khan, with the “failures of the Left after World War II.” Though the labor unions had the organizational skills and mass appeal to push for real reform, the Left allowed those advantages to dissipate on account of the theoretical confusion and imaginative limitations born of Stalinist notions of country-based socialism. However, in her determination to shoehorn Pakistani history into a Left-labor narrative, Khan seriously misrepresents or elides actualities.

In her telling, Ayub Khan’s dictatorial regime collapses not because of an all-out military revolt and a concomitant withdrawal of U.S. support, but because of labor strikes. Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto—Foreign Minister and heir-apparent of Ayub Khan and an elite landlord—becomes in Khan’s piece a populist leader by seducing the labor unions, and not by openly selling himself to the military brass as the only West Pakistani leader capable of holding back East Pakistani domination. Similarly, in Khan’s narrative Zia-ul-Haq is the original architect of Islamization, whereas in fact the policies and practices of Islamization began under Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto as early as 1973.[2] Khan stresses “Chinese opportunism” in the rise of the Afghan Taliban rather than highlighting the primary force of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and of joint U.S.–Pakistan efforts to train a local militia. She dismisses the Nawaz Sharif and Benazir Bhutto regimes of the late 1980s and 1990s as no more than the realization of the Taliban’s agenda “to find an ally across the Khyber Pass,” rather than seeing them as democratic governments (however flawed) elected by the people of Pakistan. This, of course, not only lends a far greater influence to the Afghan Taliban but also exaggerates the control those civilian governments exercised over the Pakistani military. Khan does not explain how the Taliban could set the agenda for Pakistan in the 1988 or 1993 elections when, until 1996, they were just one of a number of factions engaged in the brutal civil war then raging in Afghanistan. There are other strange lacunae buried in her narrative: She leaves unspecified who, or what, this confused and ineffective “Left” in Pakistan actually was. From what class was it drawn and in which cities? Or how did the failure to enact land reform, along with the internecine squabbling of leftist organizations and the succession of U.S.-backed military dictatorships, affect this history? The history of the Left and labor in Pakistan is certainly one of the important and largely unexamined factors in our collective efforts to understand the present. I am keen on seeing Khan make that case, but she will have to do so with far greater nuance, and with fewer liberties taken with the facts, than presented in her piece.

Yet even if Khan’s various readings of Pakistani history were defensible, her tacit embrace of U.S. imperial policies in Afghanistan and Pakistan is not. She dismisses as so much bellyaching my concern for the humanitarian crisis caused by the Pakistani military offensives in Swat, Waziristan, and Baluchistan, as well as the political crisis caused almost daily by unmanned drone attacks. For Khan, these concerns merely provide cover to the Taliban and act as a screen for their crypto-fascism. Consequently, U.S. military strategies ought to be supported, as they are the only means available for combating the Taliban. But it is hard for me to imagine that from the scorched houses and corpses of Swat and Waziristan anything resembling an international Left could possibly appear. More likely, these policies will radicalize ever larger segments of the population. More damagingly, the military-only strategies create new support networks for Islamist radicals and silence the voices of those who argue for a secular and progressive Pakistan. For Khan, pointing this out that makes me either a nationalist or a neoliberal.

I am interested neither in labels nor in identity politics. I consider myself a student of history. As is obvious, I am not providing apologia for the Taliban, but articulating a historically and politically precise context within which to understand the many groups uncritically labeled “Taliban.” Similar efforts seem to be enjoying widespread acceptance among NATO commanders in Afghanistan, but such attentiveness to cultural and historical specificity has yet to gain popularity among political analysts of Pakistan. Still, I submit that such effort towards precision and clarity alone leads towards an understanding of how the “Taliban” emerged in Pakistan, how they currently operate, and, therefore, how they might best be combated. These contexts are utterly invisible from the drone’s eye view.

A growing chorus of concerned voices now states that an uncritical embrace of U.S. military might, as it exerts itself without regards to any community, any civilian, or any local law, advance the purposes of the Taliban more than anyone else’s. Yet, there are no critical voices in the larger U.S. public speaking against America’s policies toward Pakistan. My op-ed for the Nation, to which Khan takes such exception, was just such an effort. It sought to contextualize the “Taliban are coming” hysteria, arguing that this deliberately hinders any attempt to historicize the Taliban and thus to effectively neutralize them. The Pakistani military, now being fêted with billions for fighting the Taliban, is the same Pakistani military that created the Taliban in the 1990s. The CIA that currently conducts drone missile attacks against al-Qaeda is the same CIA that in the 1980s provided the mujahideen with Stinger missiles and called them “freedom fighters.” More precisely: I have little faith in the healing power of U.S. bombs.

I remain deeply troubled by the violence unleashed by these “Taliban” organizations against Pakistan’s cities and inhabitants. If Khan had bothered to look beyond my short piece in the Nation, she would have found ample evidence on my blog that I have, for the past five years, consistently spoken and written against the religious extremists and for democracy and liberality in Pakistan. I have written consistently against the Pakistani military state and its corrosive politics and I have argued for a check on rank U.S. policies in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Pakistan.[3] It is fair to argue that I lay too much stress on the “Taliban are coming” narrative at play in U.S. policies and media, and far less effort on denouncing every single Taliban atrocity. But it is simplistic to assume that I cannot hold the Taliban in utter contempt, and completely responsible for their terrorism, while maintaining that the U.S.-Pakistani understandings of the policies based on them are misguided.[4]

The gist of my Nation piece was this: the Pakistani Taliban lack mass appeal. There is no way in which they can overthrow the state of Pakistan. They are not a mortal threat. This is now empirically true since the Taliban were famously within 60 miles of Islamabad in March 2009 and, well, Islamabad still stands—however bloodied. We heard no more about the imminent demise of Pakistan once the Pakistani army mobilized and created a million internally displaced citizens. We heard little about the crisis of Pakistan once another front was opened up in northern Waziristan. The way I understand it, this heightening of paranoia about the Taliban was not concerned with the realities on the ground in Pakistan but rather with the ideological and political landscape in Washington D.C. and Islamabad. Absent from the discussion, and the policies, were the historical concerns of the people of the region. This, I submit, is not only shortsighted but also strategically self-defeating.

In the last year alone, 3,021 civilians were killed in Pakistan in terrorist attacks and nearly 8,000 were injured. Additionally, nearly a million were displaced due to military operations. Even for a nation of 170 million, these are devastating numbers representing real sacrifices by the citizenry. These are realities that deserve our understanding and our analysis just as much as our collective concern for the rising tide of the“Taliban.” I focus on the people of Pakistan because I continue to have hope in them. I have no opinion on whether the “Left” has failed Pakistan. I do know that a broad coalition—composed of clerical and other workers, lawyers, and community activists—came together and threw out the military dictator in 2008 after a nine-year stint in power. In the election that accomplished this, the Pakistani people also roundly rejected all religious parties, embarking instead on a daring journey towards electoral democracy. |P

[1]. Atiya Khan, “The Poverty of Pakistan’s Politics (PPP)” Platypus Review 18 (December 2009).

[2]. In fact, the constitution Bhutto pushed forward in 1973 represents the most concrete capitulation by the Pakistani state to the religious right, especially the Jama’at Islami. Zia-ul-Haq is properly considered the architect not of the Islamization, but of the “Sunnification” of Pakistan. Thus, Zia only perfected a process initiated by Bhutto.

[3]. See the archives at Chapati Mystery.

[4]. The groups now collectively labeled the “Taliban in Pakistan” are in fact an amalgamation of various groups—from states’ rights advocates in Swat to tribal warlords in Waziristan to trained militia (against India in Kashmir) in southern Punjab. More than a few are now allied with domestic anti-statist organizations like the Lashkar-e-Taiba or the international ones like al-Qaeda, and some of the local warlords now have national aspirations. Collectively, they are responsible for thousands of civilian deaths in the cities of Pakistan. To effectively counter the threat they pose, we have to disaggregate them into their constituent parts, and deal with them accordingly. Some groups will respond to political dialogue, while others can only be eliminated by force or by the civil justice system. Since they claim various political goals—and it is absolutely crucial to understand that these are “political” goals though they often change from venue to venue and from spokesman to spokesman—we have to engage them within the political realm. This is where U.S. endorsement of the rigged Afghan election, and the longer history of maintaining Karzai’s puppet regime, leave us with a significant political handicap. This also means that political legitimacy must be stripped from these groups. The lingering issues of states’ rights for Swat and Baluchistan require political solutions. The Pakistani military must remain under civilian political leadership and military solutions cannot be allowed to escalate into open-ended civil warfare.

The politics of the groups lumped together under the “Taliban” label is religious in its markers, its symbols, and its public face. This means that any counter-strategy must also include a public effort to “reclaim” the religious front. These groups are heavily armed and supplied in consequence of public donations, the illicit trades in heroin and electronic media, and direct funding that still comes from sources both internal (whether the continued involvement by Pakistani intelligence agencies or other social and civil groups) and external (diaspora communities as well as Saudi Arabia). The state of Pakistan must criminalize weapons possession and revoke licenses in order to start an effort to clean out the cities and stop the influx of smuggled weaponry. The recruits are overwhelmingly young, male, and illiterate. As such, they are strongly against the existing status quo, women, and education. The reform of primary and secondary education (including madrasas) should also be a priority. The state needs to enshrine the right to education within the Constitution.