Film Review: Public Enemies

Ryan Hardy

Platypus Review 18 | December 2009

GIVE THE MAN full points for timing. Released less than a year after the onset in the summer of 2008 of the global economic crisis, and now available on DVD, Michael Mann’s Public Enemies captures perfectly, if unconsciously, the political condition of our time. The film tells the story of John Dillinger, a bank robber who was elevated by the desperation of the Great Depression into an iconic outlaw and an enduring American folk hero. A brilliant filmmaker, Mann must be an economic genius, if not an outright clairvoyant, to have successfully planned his film to coincide with this recent summer of American discontent. Or, if this sounds like too much, then certainly Mann was awfully lucky. For otherwise adverse conditions conspired to produce a most receptive climate for Public Enemies.

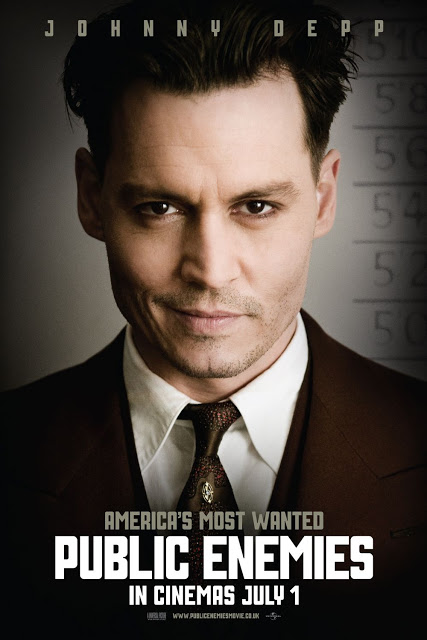

The figure of John Dillinger represents exactly the type of solitary, emotionally complex high-achiever around whom Mann prefers to build his films. The majority of his characters have been standard-issue good guys, but Mann has always been equally attracted to, and has never shied away from, protagonists on the other side of the law, from the tortured safecracker Frank (James Caan) in his debut feature, Thief (1981), to the disciplined yet romantic bank robber Neil McCauley (Robert De Niro), the outlaw half of the criminological dyad that defines Heat (1995)—Mann’s greatest film yet. As in Heat, the lead characters of Public Enemies are a robber and a cop, Dillinger and FBI agent Melvin Purvis (Christian Bale). However, whereas Heat draws strength from the parallels between its two lead characters, Public Enemies gives unquestioned pride of place to Dillinger, played by the magnetic Johnny Depp.

With the preeminent leading man of our times in a starring role and a major Hollywood director at the helm, Public Enemies succeeded as a summer blockbuster. And yet, the film demands closer scrutiny. After all, it is a film about the ferment and chaos of the Great Depression released at a time when talk of both a second Depression and second New Deal is rampant. Yet, John Dillinger was, at bottom, little more than a nondescript criminal whom law enforcement’s desperate public quest to apprehend transformed into an icon.

Using Dillinger as a starting point, Mann accomplishes something unique with Public Enemies. Although innumerable films have depicted this key period in American history, Mann’s is one of only a handful to take into account the era’s enduring appeal, its brutality and its pivotal place in the development of contemporary America.

Like many of Mann’s films, Public Enemies begins with a dynamic set piece, in this case the escape from prison of Dillinger and his cronies. As in Heat, the incompetence of one of Dillinger’s henchmen causes a snag in the breakout and leads to an unnecessary death. Absolutely pitiless in his retribution, Dillinger then throws the man from a speeding automobile. After their escape, he and his gang return to their criminal careers just where they left off, enjoying both the good life of fine dining and whorehouse excursions while knocking over banks in a technically assured, crisply professional fashion. It is not long before this hedonistic lifestyle brings Dillinger into contact with the object of romantic interest in the film, Billie Frechette (Marion Cotillard). Dillinger’s romance with Frechette evokes a powerful nostalgia for the thirties as a time when “men were men and women were women.” Their love affair begins with a dance to the song “Bye Bye Blackbird,” the tune of which is reprised repeatedly thereafter. From this first meeting their romance develops through scenes of passionate verbal intercourse. One line Dillinger delivers in one such scene typifies the appeal of supposedly simpler times: “I like baseball, movies, good clothes, fast cars, whiskey… and you. What else you need to know?” And so with this succinct yet evocative proclamation of love, and only the briefest hint of any angst about the relationship’s future, Mann portrays an idealized romance crucial for his portrait of Dillinger as a man of preternatural resolve and ability. While both Dillinger’s line and the affair it inaugurates seem simplistic, this simplicity is in many ways the point. Unlike the contemporary trope of anxiety-ridden lovers, Dillinger loves with pure intensity, if not pure intent.

And yet, the time period depicted in the film was in fact nowhere near as uncomplicated as Mann’s film suggests. Indeed, few moments in American history were more pregnant with revolutionary possibilities than was this, a time that saw both the rise of populist demagogues such as Huey Long and Father Charles Coughlin and massive labor mobilization with a parallel swelling of the ranks of the American Communist Party. In this regard the “Dirty Thirties” may be second only to the period of the Republic’s birth and the transformative chaos of the Civil War (the “Second American Revolution”), so much so that the film cannot wholly fail to depict it, as for instance in the social churning that renders the exploits of Dillinger and his confrères possible. These violate the security of governmental institutions while simultaneously wreaking havoc on the whole apparatus of state power. This is where Melvin Purvis and the FBI enter the picture. After all, the very title of the film comes from Dillinger’s designation by the FBI as “Public Enemy Number One,” a sobriquet coined by the ambitious head of the organization, J. Edgar Hoover, played Janus-faced by Billy Crudup. It is Hoover more than Purvis who is Dillinger’s real counterpart in the film. Whereas Dillinger is both a throwback and an innovator, a Wild West-style bandit who uses superior technology (telephones, very fast cars, roaring Thompson machine guns) to elude corrupt and incompetent cops, Hoover is the organization man. Self-consciously modern, Hoover embodies the nascent Fordist state just as it comes into its own.

Hoover first appears in the film at a Senate subcommittee grilling in which he is compelled to confess that, although he is the head of a developing national police force, he himself has never made an arrest. This, Hoover argues, is because he is an administrator. His goal, apparent throughout the film, is to transform the FBI into a “modern” and professional organization with a nationwide scope, to accomplish which requires, above all, the pursuit and capture of gangsters like Dillinger.

For Mann, Dillinger is not only a criminal and, consequently, the enemy of Hoover’s vast and expanding security apparatus, but also a celebrity who thrives on public interest and adulation. Thus, in one key scene, Dillinger surprises his Canadian counterpart, the criminal Alvin Karpis (Giovanni Ribisi), by declining to participate in a kidnapping scheme because, as Dillinger says, the public has no taste for kidnappings. Like any savvy celebrity, Dillinger knows the value of his audience: “I hide out among them… I gotta care what they think.”

John Dillinger hiding in public. Film Still, Public Enemies.

In one of the film’s most fascinating sequences, Dillinger and several other criminals gather in a movie theatre to discuss their next score. All of a sudden, the film is interrupted by a public service announcement warning filmgoers about the Dillinger gang, announcing the criminals could be anywhere, even in the movie theatre. Unbelievably, and more or less in unison, the entire audience then complies with the announcer’s directive to look around to see if Dillinger might not be there among them in the theater. The eerie spectacle of such mass obedience is disturbed only by the solitary figure of Dillinger, who remains still, with a smirk on his face exuding confidence.

Eventually it becomes obvious that Dillinger’s strength is liable to fail. Although Dillinger contemptuously dismisses law enforcement as not “tough enough, smart enough, or fast enough,” Hoover’s FBI eventually does catch up with him. With all the smug confidence of the consolidating status quo Purvis tells Dillinger, “the only time you will leave this jail cell is when we take you out to execute you.” While this prophecy misses the mark and Dillinger manages to escape, never again can he regain the upper hand. Instead, he is reduced to running and hiding from the FBI. In the end, this pursuit draws both Dillinger and Purvis, each accompanied by their men, to a roadside inn, the Little Bohemia Lodge, where the film reaches a violent climax. There, the Little Bohemia’s bucolic tranquility is shattered by a shoot-out between gangsters and agents of the state.

During the exchange of gunfire, most of Dillinger’s associates are killed, along with at least one FBI agent and several innocent bystanders. Though shaken, Dillinger himself manages to evade capture and plots his return to Chicago, motivated by his love for Billie. In their desperation to catch a man they have helped build into a living legend, the FBI and the police resort to increasingly brutal tactics which culminate in an especially grim scene in which the petite and elegant Billie is tied to a chair and beaten. Compared to the romantic heights during the beginning of their affair, life has become tough for Dillinger and Billie. The nationwide noose drawn by Hoover’s FBI begins to tighten and Dillinger is drawn inexorably towards a final confrontation with his enemy.

Even a casual student of American history knows the film will end with Dillinger’s death in a hail of bullets outside the Biograph Theater in Chicago. But Mann takes his time getting to this gory finale, instead taking Dillinger on a whimsical, and wholly imagined, visit to, of all places, the very FBI office where the search for him is being quarterbacked. In this strange moment the nostalgia for the 1930s as a “simpler time” collides with the fact that such times have ended, and perhaps never really existed. On the one hand, Dillinger is able to walk around the station in a pair of sunglasses and go unrecognized. But while he is there he observes the extent of the FBI’s manhunt. Earlier in the film he claims that law enforcement agencies are not “smart enough” to ever catch him; this scene puts the lie to that boast. With relentless efficiency the FBI have collected photos of Dillinger and all the other public enemies, and noted one by one their capture or elimination, leaving only John Dillinger.

Against such a powerful foe, Dillinger cannot win. But the need to reenact his story, and especially his death, suggests that Dillinger and the outlaw ideal he represented remain powerful. The professionalization and expansion of law enforcement was but one step in the process of building contemporary American capitalism. But while Dillinger and his ilk were casualties of this process, it would be a mistake to believe they represented any kind of alternative to it. As a criminal epic in the vein of Mann’s earlier films, Public Enemies is entertaining, but the elegiac tone of its conclusion is misplaced. Instead of mourning Dillinger’s death and the untamed banditry he embodied, it would be better to lament the conditions of the present that can make mere criminality seem an appealing alternative. |P