Between Old Left and New: A postwar balance sheet

Ian Morrison

Platypus Review 18 | December 2009

THE PERIOD FROM THE FIRST WORLD WAR to the Cold War belies easy classification. Unlike the single decade associated with the New Left, this extensive and historically dense period, that of the “Old Left,” has to be broken up into decades. Indeed, this is done even in the popular imagination, in which the 1930s were a time of economic collapse and union radicalism; the 1940s, a time of “the common enemy,” fascism; and the 1950s, a time of refrigerators and consumerism, of complacency and automatic dishwashers. The 1920s are willfully neglected, or else acknowledged only with respect to the “Lost Generation,” an historical touchstone that, while important, draws us away from America, back to the Old World of Europe. But, as is often the case, actual history cuts against the grain of popular storytelling.

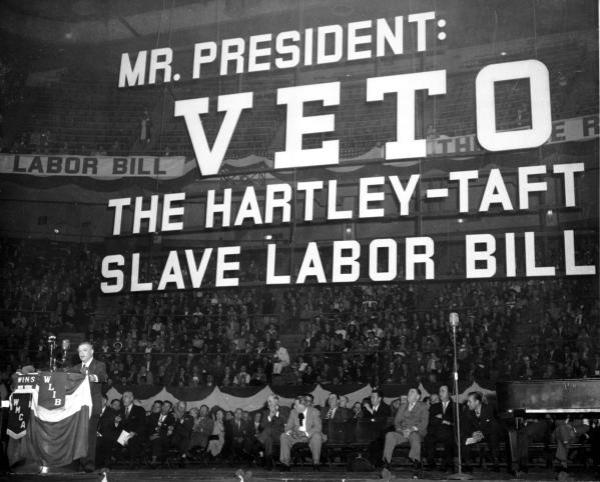

A union rally in 1947 held at Madison Square Garden in New York City to oppose the passage of the Labor Management Relations Act, generally referred to as the Taft-Hartley Bill.

When former SDS president Carl Oglesby sat down in the late 1960s to map out the contours of the New Left, he asked himself, with good reason, “Why New? Why not simply a continuation of the previous Left?” As an opening into this question, he poses others, “Why did the workers permit the purge [of communists], [why did] the people authorize the anti-Bolshevism, [why did] their leaders allow the top-down liquidation of McCarthy to provide, above all, for the continuation of McCarthyism by more subtle means?”[1] But these questions find no ready answers. So, instead, Oglesby attempts to cut against the idea of 1950s conservatism by claiming the decade also belonged to “the Chinese, the Vietnamese, the Cubans, the Algerians, [and] the decolonizing African states.”[2] He goes on to argue that the East is separate from “Western Culture,” which “appears to be distinguished by its failure to produce a class whose essential objectives transcend the capacities of the given order and whose presence would therefore force a structural transformation of the relations of production.”[3] Here we get the familiar paradigm. What is the new agency of revolutionary change, asks Oglesby and the New Left, now that the workers have failed us? The answers range from the intellectual and the student to the wretched of the earth and the subaltern.

We can no longer today evade the important questions. And the fact remains that, even if we are to believe that in the 1960s students and peasant rebels emerged as new agencies of social transformation, this does nothing to explain why the working class in the First World became depoliticized in the first place. Why was it that the revolutionary potential of the working class seemed to melt into air? How did the Old Left become depoliticized? To answer this question we must look at the history of the Left, both in terms of the possibilities it created and the fetters it imposed on itself.

First, to be clear, the conservative turn in the labor unions after the post-Second World War strike wave is an inescapably true historical development, culminating in the notorious 1947 Taft-Hartley Act. The problem that confronted the New Left—the problem of a stymied organized working class—was real. The problem persists to this day, even as our understanding of this issue, which strikes directly at the question of creating a strong Left in the U.S., remains frozen in place. C. Wright Mills, one of the intellectual catalysts of the New Left, summed up the mood of the 1950s when he wrote that union leaders were “government-made men, and they have feared—correctly, as it turns out—that they can be unmade by the government… Neither labor leaders nor labor unions are at the present juncture likely to be ‘independent variables’ in the national context.”[4] Now, Mills was drawn to the idea that, at least in the postwar situation in which he found himself, intellectuals were what he termed “the independent variable.” For Mills understood, even if many of his New Left followers did not, that the isolation of the intellectual was nothing less than a symptom of Stalinism. Mills was not interested in “leaving behind” the working class, as a political program. At the same time, he was also acutely aware of the alliance between labor and the state forged in Roosevelt’s New Deal and maintained during the Second World War as part of the alliance with the Soviet Union. To the extent that the New Left brushed aside the hostility of the “hard hats,” it not only chose to ignore the issue but, no less certainly, also blocked its own way into the history of the Left. And this, above all, fatally compromised the New Left from the beginning.

Mills began working towards a theory of the shifting social groups, and the new post-war consolidations of power, while partially under the influence of Max Shachtman’s Workers Party, an intellectual tradition stemming from the Left Opposition (commonly referred to as Trotskyism). This thwarted tradition was bitterly aware of the nightmare unfolding in the 1930s. But, unlike the New Left, and unlike thinkers such as C. Wright Mills, Shachtman put forth a different and far more controversial conclusion in 1950: “It is not Marxism that has failed, as many gloomy critics find it so popular to say nowadays; it is the Marxian dogmatists who have failed.”[5]

To grasp why there is no adequate theoretical tradition in America, one must first abandon the idea of the radical 1930s so popular today, and focus instead on the preceding decade. As Christopher Lasch argued, “By the middle twenties American radicalism had acquired the characteristics it has retained until the present day: sectarianism, marginality, and alienation from American life.”[6] Unlike in Europe, American radicalism was not split by social democracy. In 1917, at the American Socialist Party’s emergency convention in St. Louis, it espoused an openly internationalist perspective, opposing on that basis America’s entry into the war. But such declarations must be viewed in proper perspective. At the only Socialist-led action in opposition to the war, which took place in Boston, “hundreds of Socialists were beaten and forced to kiss the flag on their knees.”[7] The anti-war tendencies in the U.S., which might have been the springboard for a radical international socialism, lacked effective organization.

It was not until the end of the First World War that these bad omens were fully realized in the actual political situation. As Shachtman recalled in a speech he gave in the late 1960s,

The once spectacular IWW had all but died-out completely. The Farm-Labor party movement of the early twenties collapsed after the defeat of Senator La Follette in the 1924 presidential election. The official labor movement of that time was conservative, narrow, smug, and small. Before it was split in 1919, the united Socialist Party had well over a hundred thousand dues-paying members in its ranks. It is certain that the communists and socialists parties had less than 20,000 members between them ten years later when the [stock marked crash] erupted.[8]

Max Eastman, James P. Canon, and Big Bill Haywood at the Fourth World Congress of the Comintern held in Moscow in 1922. At this meeting, Cannon successfully argued for the legal and open functioning of the Communist Party of America.

Displaying a stunning lack of perspicacity, the communists of the 1920s set American Leftist politics on a collision course, a disaster on par with and in the tradition of the failed revolution in Germany, the botched general strike in Britain in 1926, and the crushed Shanghai Commune of 1927. Effectively writing off the entire organized working class in favor of underground irrelevancy, the majority of American communists adopted a supercilious attitude toward the explosive strike wave that swept the country in 1919. When, after years of inter-party struggle and the intervention of the Soviet government, the communists finally formed a legal party that working class Americans could actually read about and join, the radical tide had turned. At the 1921 founding conference of the legal party, future leader of the American Left Opposition, James P. Cannon, lamented, “We have a labor movement that is completely discouraged and demoralized. We have an organized labor movement that is unable on any front to put up an effective struggle against the drive of destruction, organized by the masters. We have a revolutionary moment which, until this inspirational call for a Workers’ Party Convention, was disheartened, discouraged, and demoralized.”[9] Future rationalizations for failing to strike when the iron was hot generally express, as did the Communist Party in 1919, contempt for the potential of the organized working class in the U.S.

Following the reigning dogma of the Comintern in the mid-1920s, communists attempted to align themselves with the Farm-Labor Party movement. The rather remarkable assumption behind this was that the most advanced capitalist country in the world at that time had not yet developed to the stage where the formation of a genuinely proletarian party was appropriate. Indeed, it was thought American workers may even be incapable of forming something comparable to the Labour Party in the United Kingdom. The U.S. working class was, to the communists in the 1920s, unripe. But to leftists familiar with American trade unions, far from being “unripe,” the situation of American radicalism desperately called out for the theory and the kind of political support it received during the fight for a legal party. The American situation was, in other words, plenty ripe; it just had to be “plucked” by an internationalist and revolutionary Left. As James P. Cannon pleaded, during his factional fight with the Comintern representative,

The American movement has no counterpart anywhere else in the world, and any attempt to meet its problems by the simple process of finding a European analogy will not succeed. The key to the American problem can be found only in a thorough examination of the peculiar American situation. Our Marxian outlook, confirmed by the history of the movement in Europe, provides us with some general principles to go by, but there is no pattern, made-to-order from the European experience, that fits America today.[10]

Yet, despite such pleas, American communists, along with their international counterparts, slid farther and farther to the right throughout the 1920s. It is on this very issue, and for this reason, that at the end of the decade Cannon broke with Stalinist orthodoxy in favor of Trotsky’s Left Opposition.

Commenting on the rightward drift of communists in the 1920s, Shachtman argued, “Everything that had distinguished Communists from Socialists at the time of the historic split between them after the First World War was sunk without a trace [by the start of the 30s]. In fact, the ‘Popular Front’ position of the Communist Party on all questions of theory and politics would have repelled the most extreme right-wing socialism at the time of the split in 1919.”[11] This statement may appear rather bombastic to the romanticized view of the radical 1930s, the counter-example undoubtedly being the formation of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). Bracketing for a moment the Moscow Trials and the unchallenged rise of fascism in Europe, let us take a closer look at the Popular Front politics of communists in the CIO. At this time communists had taken a monumental rightward leap: from a position of out-and-out disaffiliation with every non-communist union, the communists, under the aegis of the Popular Front, became uncritical cheerleaders for Roosevelt’s New Deal, working closer to the Democratic Party than any previous American radical could ever have imagined.

The communists’ pernicious role in the New Deal alliance between labor and the state has had complex as well as lasting results. When the Second World War was in full swing and strikes threatened military production, the CIO, in line with Popular Front thinking, supported no-strike pledges, a portentous state directive that culminated after the War in the Taft-Hartley Bill. This in effect outlawed not only wildcat strikes but sympathy strikes and, indeed, all labor action deemed undesirable to the state. The legislation allowed the CIO to purge the communists, placing organized labor firmly within the dualistic Cold War framework, which profoundly affected political action in the following decades. These difficulties were further compounded by the failure of the CIO’s all too timid attempt of 1946–53, known as “Operation Dixie,” to organize in the South, a failure that helped trigger the Cold War merger between the CIO and American Federation of Labor in December 1955, which in effect ended the CIO’s period of militant organizing. December 1955, as any good American history buff knows, was also the start of the Montgomery Bus boycott. The missed opportunity, during the birth of the New Left, simply takes one’s breath away.[12] Yet, the source of such problems lies in the 1920s, when American communists squandered the possibility of labor becoming an “independent variable,” rather than a lackey for the state.

In all matters essential to thinking through the history of the American Left, especially the need for a party of labor, a place where the tension between reform and revolution can be dialectically propelled, the communists of the past give us little critical insight; they even conspired against those who might have provided some. American communists offered ossified thinking and a shift to the right in practice, withering along with the New Deal they supported, dying in the war whose aims they could not influence. Yet, posed against this was a different current of thought, whose hopes were pinned on the unbounded dynamism of the American working class, a hope that goes all the way back to Marx, who wrote in Capital,

In the United States of America, every independent workers’ movement was paralysed as long as slavery disfigured a part of the republic. Labour in a white skin cannot emancipate itself where it is branded in a black skin. However a new life immediately arose from the death of slavery. The first fruit of the American Civil War was the eight hours’ agitation, which ran from the Atlantic to the Pacific, from New England to California with the seven-league boots of the locomotive.[13]

Three years before the first volume of Marx’s masterpiece was published, the International Working Men’s Association (which Marx served as Secretary) wrote as follows to Republican Party leader and U.S. President Abraham Lincoln,

The workingmen of Europe feel sure that, as the American War of Independence initiated a new era of ascendancy for the middle class, so the American Antislavery War will do for the working classes. They consider it an earnest of the epoch to come that it fell to the lot of Abraham Lincoln, the single-minded son of the working class, to lead his country through the matchless struggle for the rescue of an enchained race and the reconstruction of a social world.[14]

In this same spirit, and in no less perilous a time, Trotsky proclaimed, completely out of sync with the dominant thought of the 1930s, most especially among “communists,” that a socialist America was not only possible, but desirable:

The governments of Central and South America would be pulled into [the North American Soviet] federation like iron filings to a magnet. So would Canada. The popular movements in these countries would be so strong that they would force this great unifying process within a short period and at insignificant costs. I am ready to bet that the first anniversary of the American soviets would find the Western Hemisphere transformed into the Soviet United States of North, Central and South America, with its capital at Panama.[15]

Why must this, even as a distant hope or dream, appear to the Left today, so concerned with “anti-imperialism,” as a sacrilege?

How did the Left depoliticize a generation, and future generations, up to this day? The question with which Oglesby began is where we too must start. But, rather than searching the nooks and crannies of either the university or the Third World for an alternative revolutionary subject, we would do better to revisit the history that Oglesby and the New Left first misunderstood, then obscured. It was Stalinism itself, and not the purging of the Stalinists from the American trade unions in the heyday of McCarthyism, that most fundamentally conditioned the subsequent rightward turn of the working class. Moreover, the seeds of this were planted even before Stalinism had fully taken hold of American communism. At this critical juncture of history we can see, in figures like Shachtman and Cannon, glimpses of a nascent alternate future that had died by the end of the 1930s. The same might have been visible to the likes of Oglesby. Had he looked to it, the long detour of the New Left might have been avoided. That generation might conceivably have done what we must do now, namely undertake a critique of the history of the Left that, precisely because it takes a critical stance, declines to take the historical failure of the Left for granted. |P

[1]. Carl Oglesby, “The Idea of the New Left,” in The New Left Reader, ed. Carl Oglesby (New York: Grove Press, 1969), 2.

[2]. Ibid., 4.

[3]. Ibid., 9.

[4]. C. Wright Mills, The Power Elite (New York: Oxford University Press, 1956), 263–65.

[5]. Max Shachtman, “Reflections on a Decade Past,” New International 16:3 (May–June 1950): 131–144.

[6]. Christopher Lasch, The Agony of the American Left (New York: Knopf, 1968), 40.

[7]. Theodore Draper, The Roots of American Communism (New York: Viking Press, 1957), 96.

[8]. Max Shachtman, “Radicalism in the Thirties: The Trotskyist View,” in As We Saw the Thirties: Essays on Social and Political Movements of a Decade, ed. Rita James Simon (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1969), 10–11.

[9]. Draper, Roots of Communism, 341.

[10]. James P. Cannon, “The Workers Party Today—And Tomorrow,” in James P. Cannon and the Early Years of American Communism: Selected Writings and Speeches, 1920–1928 (New York: Prometheus Research Library, 1992), 137.

[11]. Shachtman, “Radicalism in the Thirties: The Trotskyist View,” 34.

[12]. For a fuller analysis on the effects of the New Deal alliance on the Civil Rights Movement, see Adolph Reed, “Black Particularity Reconsidered,” Telos 39 (Spring 1979): 71–93.

[13]. Karl Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, A Critique of Political Economy, trans. Ben Fowkes (London: Penguin, 1990), 414.

[14]. Karl Marx, 29 November 1864, address of the International Working Men’s Association to Abraham Lincoln, The Bee-Hive 169 (7 November 1865).

[15]. Leon Trotsky, “If America Should Go Communist,” Liberty, 23 March 1935.