Book Review: Michael Rudolph West. The Education of Booker T. Washington: American Democracy and the Idea of Race Relations.

New York: Columbia University Press, 2006.

Greg Gabrellas

Platypus Review 15 | September 2009

IF THE COLOR LINE WAS THE PROBLEM of the American 20th century, then the 20th century did not manage to solve it. De jure segregation ended some forty years ago, and American social norms mostly bar the public expression of racist sentiment or stereotype. Yet by any measure—access to quality healthcare and education, rate of incarceration, etc.—black Americans remain proportionally worse off than their white peers. There remains a color line, but why? This question has bred a whole genus of specious answers. Take the Bell Curve genetic inheritance theory: poor genes make for poor IQ, poor IQ makes for poor minds, and poor minds make for poor people. For slightly less controversial variations, substitute “welfare queen” or “single mothers.” Rightly uncomfortable with transferring blame for a social pathology onto its victims, anti-racism activists offer another explanation. Racism, they claim, persists—invisible, yes, but inherent in oppressive social structures caused by the instincts of white society. For instance, when faced with two equally qualified candidates, employers will hire the one with the white sounding name. Such unconscious discrimination stalks black Americans, dooming them to social death. The persistence of the color line, this “anti-racist” explanation suggests, is a problem of race relations. Change the race relations—through multicultural education, affirmative action, and supporting black-owned businesses—and the color line will vanish. Call this the “race relations paradigm.”

Michael Rudolph West, in his recent study, argues that the race relations paradigm begins with Booker T. Washington. This is an unusual suggestion: Few consider Washington as a theorist of much of anything, let alone the inventor of a paradigm. Depending on one’s viewpoint, Washington is either a pragmatic race leader, doggedly working for the advancement of his people, or an Uncle Tom, a race traitor who sells out to segregationists. But West neither glorifies nor excoriates his subject, nor does he portray Washington merely as the clever tactician he certainly was. West’s Washington appears as a theorist of the “Negro question,” struggling to find political possibility in the wake of Reconstruction’s failure. Like other theorists of the Negro question, for instance Thomas Jefferson or Gunnar Myrdal, Washington is out to understand and resolve the place of black people in America. But West also suggests that this may not be the right question, that there might be another, more fruitful way of understanding Washington as a theorist of the Negro question. Thinking race qua racial difference delinks the problem from broader questions of politics, class, and capitalism. The problem of race after this delinking appears susceptible to resolution without broader social change. Jefferson’s “solution” was simply to ship adult slaves back to Africa, and undo the whole problem. Although Jefferson’s idea of colonization never had broad appeal, Washington’s solution, by contrast, has had a real, lasting legacy. West calls this solution the theory of “good race relations.”

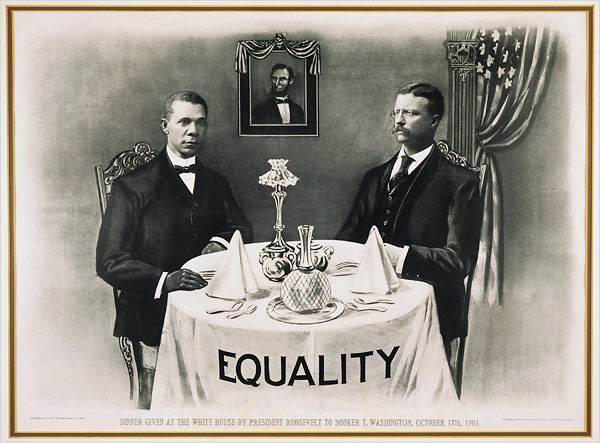

Lithograph commemorating Booker T. Washington’s 1901 White House dinner with President Theodore Roosevelt.

Unlike other biographies of its subject, West’s Education stands out as a unique synthesis of political and social history, psychology, and ideological critique. As West shows, Washington’s education was not the “industrial education” he later advocated for others. Rather, Washington’s theories of race and the meaning of history for understanding the “Negro question” must be understood with reference to the unfinished, but stymied, history of Reconstruction itself—what Eric Foner has called “America’s unfinished revolution.” West argues that the race relations paradigm, which he calls Washingtonianism, displaced the radical democratic aspirations of Reconstruction. Washington himself participated in Reconstruction electoral politics as a teenager. For example, he put radical Republican ideas into action as secretary of the Tinkersville, West Virginia Republicans (160). Before the collapse of the Freedman’s Bureau and, with it, black participation in Southern governments, black politicians overtly fought for mass political franchise, the redistribution of land and property, and social integration. Yet out of his disappointment with his experience as a freedman and Republican activist, Washington fashioned a new mission. In the wake of Reconstruction’s failure, instead of fighting for social power, Washington argued that blacks should work hard and whites should play nice.

There was a real appeal to the idea of “good race relations” in post-Reconstruction America. This way, despite the grim retrenchment of landlords and capitalists, progressives could still feel like one was advancing the cause of black people. Washington, a good-hearted opportunist to the core, did what opportunists usually do: He accepted defeat, while refusing to call it by that name. Reconstruction attempted, and failed, to bring real social equality to the emancipated slaves. Washington offered a comfortable solution that seemed to work; hard work and mutual respect might not fully substitute for the radical Republican agenda, but they could offer harmony and “progress.” Washington and his race relations paradigm helped to bury radical Reconstruction by claiming to share many of its goals. West argues, it was only in the context of this political failure that Washington found a broad hearing among sympathetic liberals, and established himself as de facto race spokesman and leader. But Washington not only reconciled blacks to their exclusion from the polls, he was complicit with it. “Progress” was Washington’s name for (and affirmation of) the diminished political horizons blacks faced after the collapse of Reconstruction: political disfranchisement and segregation. If American society is basically well-ordered, but segregated, and if emancipation had finally secured the precondition of black improvement despite the conflicts engendered by Reconstruction, then at least blacks could control their lives more by improving themselves and others’ perceptions of them. Washington himself, in his Atlanta Address of 1885, gives the best explication: “In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.” Separate and unequal, but working real hard.

West’s story of late 19th century radical defeat closely resembles another trajectory closer to our own time: the decline of Civil Rights and the rise of Black Power, the ideological consequences of which remain with us today. After ending de jure segregation, the leaders of the Civil Rights Movement attempted to address and resolve the social position of American blacks. Bayard Rustin urged cooperation with the labor movement, but the means of attack proved inadequate, and the attempt failed. Militant activists then turned to slogans such as “community self-determination,” and exhorted their colleagues to promote racially segregated cooperatives and institutions. The Black Panthers seem to have little in common with old Uncle Booker; like the race relations paradigm, however, the politics of Black Power marked a turn towards internal racial transformation rather than transforming the political and economic order. Today’s proponents of “good race relations” take a less militant tone, but they, too, look inwards. Multiculturalism views respect between racial communities as imperative to progress. Yet, capital accumulates among a wealthy few and social disparities between the rich and the poor continue to increase. When activists substitute “good race relations” for social politics, the entire working class—white and black—suffers.

If the ideology of “good race relations” obscures crucial aspects of anti-black racism and poverty, then the critique of this ideology should point toward the overcoming of racism. However, West leaves us critical of the race relations paradigm but unsure where to turn for a more adequate analysis of American racism. Most fundamentally, West leaves the long-term defeat of radical Republicanism largely undiagnosed. After all, post-Reconstruction politics were not solely dominated by Washingtonianism. Populist, socialist, and communist movements all tried and failed to eliminate racism through the late 19th and 20th centuries. The failure to ground his analysis of the race relations paradigm more firmly in the history of the Left thus leaves underspecified West’s implied critique of 20th century anti-racist politics. For instance, although he suggests that the civil disobedience strategies of the Civil Rights Movement were effective because they broke the shallow consensus of segregation endorsed by Washington and his followers, it is unclear where the forerunners to Civil Rights fit into the story. West’s work is therefore only a promising beginning to reassess the ideology of the Civil Rights Movement; nevertheless, it still performs a vital service. By tracing the race relations paradigm to the rise and ignominious defeat of Reconstruction, West calls attention to the historical roots of what has become common sense about race today. He challenges us to imagine the possibility of a movement for social reform that is not satisfied with the scraps the ruling classes are willing to throw its way. |P